Texas Water Tour: Statewide Water Planning and Innovations

Statewide Snapshot | Print Snapshot (PDF)

Introduction

Water planning and management in Texas is necessary to prepare for future weather events that affect water resources and to ensure enough water is available for future generations of families and businesses.

Texas’ population has exploded in recent years. Between 2010 and 2020, the state’s population grew more than any other state — nearly four million people, or 16 percent (compared with a 7 percent increase in the U.S. population). State demographers estimate that by 2050 Texas’ population will balloon to more than 47 million people (PDF), all of whom will require reliable and clean water sources to lead healthy and productive lives.

Moreover, adequate water planning and management is vital for sustaining Texas’ booming business climate. In 2021, Texas was a top ranked state for the number of private-sector capital investment projects within its borders. In that year, 63 businesses relocated their headquarters to Texas from other states. Small businesses thrive in Texas because of factors including the state’s minimal tax burden, skilled workforce and relatively low cost of living. But, like households, these businesses rely on access to reliable and clean water sources to operate.

Continued economic prosperity and quality of life in Texas depends on the successful implementation of water management strategies and infrastructure projects designed to conserve and bolster the state’s water supply to meet growing demand.

Texas Water Planning and Management

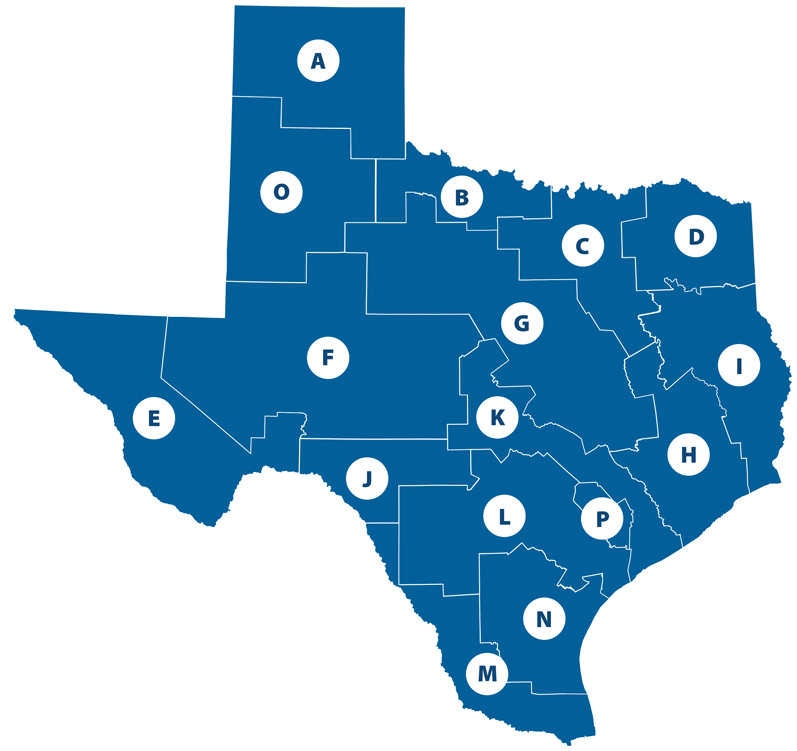

Water planning in Texas is complex because of the state’s size, population and geographic diversity; thus, a one-size-fits-all approach does not work. In 1997, the Texas Legislature enacted a “bottom-up,” consensus-driven water planning process utilizing the state’s 16 water planning regions, each with their own unique set of water needs (Exhibit 1).

Texas Water Planning Regions

- Panhandle

- Region B

- Region C

- North East Texas

- Far West Texas

- Region F

- Brazos

- Region H

- East Texas

- Plateau

- Lower Colorado

- South Central Texas

- Rio Grande

- Coastal Bend

- Llano Estacado

- Lavaca

Source: Texas Water Development Board

The Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), the agency that works to ensure a water secure future in Texas, releases an updated State Water Plan (SWP) every five years to guide Texas water policy and assess regional water supplies and needs 50 years into the future. According to TWDB, “Texas’ SWPs are based on future conditions that would exist in the event of a recurrence of the worst recorded drought in Texas’ history (PDF) — known as the “drought of record” — a time when, generally, water supplies are lowest and water demands are highest.” TWDB currently benchmarks the drought that occurred from 1950-57 — which cost Texas agriculture producers nearly $39.8 billion (in 2021 dollars) in direct losses and damaged more than 4 million acres — as the state’s drought of record.

Each water planning region is governed by a planning group consisting of members representing at least 12 statutorily mandated interests, including the public, county, municipal, agricultural and environmental. During each five-year planning cycle, planning groups develop their own Regional Water Plan using state funds administered by TWDB. These plans identify water supply projects and strategies to address future needs, which are incorporated in the SWP by TWDB. Many planning regions use the more recent drought of 2011 as the drought of record when developing their plans, rather than the 1950s drought that has often been used as the benchmark in the past.

Though TWDB bears the ultimate responsibility for developing the SWP, the participation of all 16 regional water groups makes the plan comprehensive and representative of the state’s diverse needs.

2022 State Water Plan: Key Points

The TWDB adopted the latest SWP in July 2021, the fifth water plan since 2002 to be developed using the bottom-up regional water planning process. The report estimates Texas’ total water demand (PDF) will increase by 8.5 percent between 2020 and 2070. However, demand differs greatly by water use category over this period:

- Municipal demand is projected to increase 62.9 percent.

- Agricultural irrigation demand is projected to decrease 19.6 percent (due to a variety of factors such as precision agriculture tools that save water and reduced availability of groundwater).

- Manufacturing demand is projected to increase 14.3 percent.

- Steam-electric power generation demand is projected to remain constant.

- Livestock demand is projected to increase 15.1 percent.

- Mining demand is projected to decrease 30.9 percent.

Exhibit 2 shows the projected population and water demand data for each region.

Projected Population Growth and Change in Demand by Water Planning Region

| Region Name | Region Letter | Population Growth | Water Demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panhandle | Region A | 52% | -25% |

| Region B | Region B | 11% | -1% |

| Region C | Region C | 92% | 67% |

| North East Texas | Region D | 65% | 19% |

| Far West Texas | Region E | 63% | 17% |

| Region F | Region F | 45% | -3% |

| Brazos | Region G | 84% | 27% |

| Region H | Region H | 60% | 32% |

| East Texas | Region I | 35% | 14% |

| Plateau | Region J | 31% | 16% |

| Lower Colorado | Region K | 87% | 17% |

| South Central Texas | Region L | 73% | 26% |

| Rio Grande | Region M | 105% | 4% |

| Coastal Bend | Region N | 21% | 9% |

| Llano Estacado | Region O | 49% | -27% |

| Lavaca | Region P | 12% | -1% |

| Texas | 73% | 9% |

Source: Texas Water Development Board

The 2022 SWP also estimates that Texas’ existing water supply — which consists of surface water, groundwater and water reuse (i.e., wastewater) — will decline by 18 percent between 2020 and 2070 (Exhibit 3).

| Source | 2020 (acre-feet) | 2070 (acre-feet) | Percent change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface water | 7,232,000 | 7,080,000 | -2.1% |

| Groundwater | 8,912,000 | 6,023,000 | -32.4% |

| Reuse | 620,000 | 714,000 | 15.2% |

| Texas | 16,764,000 | 13,817,000 | -17.6% |

Source: Texas Water Development Board, State Water Plan (PDF), p. 77

Water Management Strategies and Projects

Texas’ 16 planning groups each recommend specific water management strategies (PDF) to increase water supply and/or reduce water demand in their respective regions to meet potential shortages. In the 2022 SWP, planning groups recommended about 5,800 water management strategies and more than 2,400 water management strategy projects (i.e., new infrastructure).

Water projects typically require large initial investments (PDF), or capital costs, followed by decades-long payback periods. The SWP estimates that implementing the recommended water management projects will require $80 billion in capital costs over the next 50 years — and expects $47 billion of that to come from state financial assistance programs.

In 2013, the Texas Legislature established the State Water Implementation Fund for Texas (SWIFT) (PDF) , a financial assistance program administered by the TWDB for water projects designed to conserve existing water supplies and create additional water supplies. (The Texas Treasury Safekeeping Trust Company manages these funds.) SWIFT provides project sponsors (e.g., municipalities, counties, river authorities) low-cost financing options for water projects recommended in the SWP that require long-term borrowing. These projects often involve the construction of new infrastructure; however, some projects involve planning, design and/or acquisition without any construction. SWIFT has committed nearly $9.2 billion in financial assistance for 58 recommended SWP projects (PDF) since the program began in 2015.

The TWDB also offers several other state and federal financial assistance programs for water projects that may or may not be included in the SWP. As of May 31, 2022, the TWDB has committed approximately $32.6 billion in cost-effective loans and grants since the agency's inception in 1957.

More than two-thirds (69%) of water management strategies recommended in the SWP rely on creating additional water such as surface water or groundwater, while the remaining strategies rely on demand management. The SWP projects the highest percentage of new water supplies in 2070 to come from strategies based on surface water, followed by water reuse, groundwater and seawater (Exhibit 4).

New Water in State Water Plan, Percent Share by Water Resource,

2020 and 2070

2020

2070

| Source | 2020 | 2070 |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in Demand* | 50.9% | 30.9% |

| Surface Water | 24.2% | 37% |

| Groundwater | 17.6% | 14.5% |

| Reuse | 7.2% | 15.1% |

| Seawater | 0.2% | 2.5% |

*Reduction in demand is projected to come from agricultural, municipal and other conservation efforts.

Source: Texas Water Development Board, 2022 SWP interactive dashboard

Surface water

Texas’ surface water supplies (PDF) come from 187 major reservoirs, 15 major river basins and eight coastal basins. Basins are areas drained by a river and its tributaries; and reservoirs are large artificial lakes. (Texas has only one natural lake, Caddo Lake on its border with Louisiana.)

There are two types of reservoirs: on-channel, created by damming rivers and restricting the downstream flow of water, as with the Highland Lakes chain in Central Texas; and off-channel, created by piping water from a river to an artificially constructed lake separate from the river itself, such as Wharton County’s new Arbuckle Reservoir (estimated to be operational in 2023).

Because some parts of Texas typically are much drier than others, a common strategy to meet water needs is to transfer water between different river basins to supplement existing supplies. This practice, called interbasin transfer, involves moving water via canals or pipes. Some areas in Texas receive most of their water from interbasin transfers.

In 2020, surface water made up about 24 percent of new water supplies in Texas. By 2070, the SWP estimates surface water will increase to 37 percent of new water supplies, as a result of water management strategies based on surface water, such as the 23 new major reservoirs recommended by regional planning groups.

Bois D’Arc Lake, northeast of the city of Bonham in Fannin County, will be the newest reservoir in Texas and has received nearly $1.5 billion (PDF) in funding commitments from SWIFT, the largest commitment total of any project under the program.

Groundwater

Groundwater resides in aquifers, or large underground spaces made of rock and sediment. In Texas, there are nine major aquifers — which produce large amounts of water over large areas — and 22 minor aquifers − which produce relatively small amounts of water over large areas or vice versa. Water management strategies in the SWP often include the drilling of new wells to tap groundwater held in aquifers, especially in rural municipalities. The city of Marfa received $705,000 in funding commitments under SWIFT for construction of an additional well.

Another strategy gaining momentum in Texas is aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) (PDF). ASR is the practice of actively injecting water from a different source or location, when available during wet periods, into an aquifer to be stored for later use and recovery during dry periods. ASR is only possible in areas of the state with specific geologic features and in areas where only the project sponsor may retrieve the stored water. Three ASR facilities currently exist in Texas (serving El Paso, Kerrville and San Antonio), but more water providers across the state are expressing interest in ASR. In the 2022 SWP, regional planning groups recommended 27 projects that would establish ASR facilities or create pilot programs.

In 2020, groundwater made up 17.6 percent of new water supplies in Texas. By 2070, the SWP estimates that groundwater will decrease to 14.5 percent of new water supplies. ASR alone will account for 3 percent of the state’s total new water supplies in 2070.

Water reuse

Water reuse is the practice of reclaiming and preparing domestic or municipal wastewater for future beneficial use through water treatment processes that meet certain quality standards. Though not the most appealing, wastewater is reliable, and for a price, it can be cleaned and become a source of its own.

There are two categories of water reuse: direct reuse, which is the practice of moving water that has been cleaned at a wastewater treatment facility directly to a distribution system for beneficial use, such as irrigating a golf course or cooling a power plant; and indirect reuse, which is the practice of discharging treated wastewater into a lake, aquifer or other environmental buffer for later use. The city of Austin received more than $65.6 million in SWIFT funding commitments for a direct reuse strategy.

In 2020, wastewater reuse made up 7.2 percent of new water supplies in Texas. By 2070, the SWP predicts that reuse will make up 15.1 percent of new water supplies and surpass groundwater as a source of new supplies. Fifteen regional planning groups recommended water reuse as a water management strategy in the most recent SWP.

Desalination

Desalination is the process of removing salts and other minerals from seawater and brackish water (water that contains more salt than freshwater but less salt than seawater). There are 53 municipal desalination facilities in Texas, all of which process brackish surface water or brackish groundwater. El Paso has the world’s largest inland desalination facility, which can produce up to 27.5 million gallons of freshwater per day.

Texas does not yet have an operational desalination facility to process seawater for municipal purposes; however, a facility in Corpus Christi is slated to be complete in December 2025 and has received more than $225 million in funding commitments from SWIFT.

A downside to desalination is the high cost of the energy and technology that it requires. According to the SWP, the average cost to produce one acre-foot of desalinated water from brackish groundwater ranges from $357 to $782, while the average cost to produce the same amount of desalinated seawater ranges from $800 to $1,400.

In 2020, groundwater desalination and seawater desalination made up 1.1 percent and 0 percent of new water supplies in Texas, respectively. By 2070, the SWP estimates that both groundwater desalination and seawater desalination will grow to 2 percent and 2.5 percent of new water supplies, respectively. Nine regional planning groups have recommended brackish groundwater desalination strategies, and three groups have recommended seawater desalination strategies.

Flood mitigation

Floods are the most common natural disasters in the world, causing devastation to both human life and the economy. Although floods are difficult to predict and near impossible to prevent in many cases, Texas is working to avert death and property damage through proper planning and structural and nonstructural flood mitigation. Structural mitigation includes seawalls, floodgates, levees and other forms of landscape modification. Nonstructural mitigation includes residential relocation, updates to zoning laws and building codes, and other methods of decreasing the amount of people and property from high-risk areas.

In response to the devastating floods caused by Hurricane Harvey in 2017, the 86th Texas Legislature in 2019 passed pivotal legislation establishing the Flood Infrastructure Fund (PDF), a financial assistance program for flood control, flood mitigation and drainage infrastructure projects. As of July 2022, the program has committed more than $433 million to 127 active and completed projects throughout the state.

The 86th Legislature also passed legislation requiring the TWDB to establish a statewide flood mitigation planning process — separate from state water planning — and to also develop Texas’ first-ever state flood plan by September 2024 and every five years thereafter. Like the SWP, the state flood plan will be based on regional input. (The TWDB has established 15 flood planning regions.)

Rain harvesting and enhancement

Rainwater harvesting (PDF) refers to the capture and storage of rainwater for future beneficial use. Rainwater harvesting has a long history in Texas. Well before the widespread use of centralized water supply systems, many Texans relied on collecting rainwater from rooftops and storing it in tanks called cisterns. Today, the same concept helps reduce demand on modern water systems and provides clean water in areas with limited to no access to water systems, especially in dry and rural parts of the state. In recent years, the Texas Legislature has codified incentives for rainwater harvesting, including an exemption from sales tax for rainwater harvesting equipment and a requirement for certain new state facilities to incorporate rainwater harvesting systems in their designs.

The SWP estimates that about 5,000 acre-feet per year in new water supplies will come from recommended rainwater harvesting strategies by 2070.

Rain enhancement, or cloud seeding, is a weather modification technique to encourage precipitation from clouds by using ground generators or aircraft to disperse certain particles in the air that mimic the natural particles responsible for forming raindrops or snowflakes inside clouds. In Texas, some political subdivisions such as water conservation districts employ cloud seeding as part of their diverse water management strategy portfolios to combat droughts, replenish aquifers and reservoirs and support the state’s growing population. In 2021, the Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District budgeted $123,394, or about 3 cents per acre, for its cloud seeding project that covers the district’s more than four-million-acre territory.

The SWP estimates that about 5,000 acre-feet per year in new water supplies will come from recommended cloud seeding strategies by 2070.

For additional insights, see The 2022 State Water Plan and Innovations in Texas Water Systems, Fiscal Notes, June-July 2022.

Links are correct at the time of publication. The Comptroller's office is not responsible for external websites.