Texas Water Tour: Canal Systems

Canal Systems Snapshot | Print Snapshot (PDF)

Introduction

Once water is sourced, it must be transported to those who need it. One of the most common ways to do this is through canals. A canal is an artificially made waterway that transports water for crop irrigation, industry and municipal uses and provides a means of transportation for ships and cargo. Canals enhance the efficient distribution of water and resources, produce cost savings, and boost standards of living and economic activity that benefit all Texans. This overview covers both transportation and irrigation canals.

Transportation Canals

Gulf Intracoastal Waterway

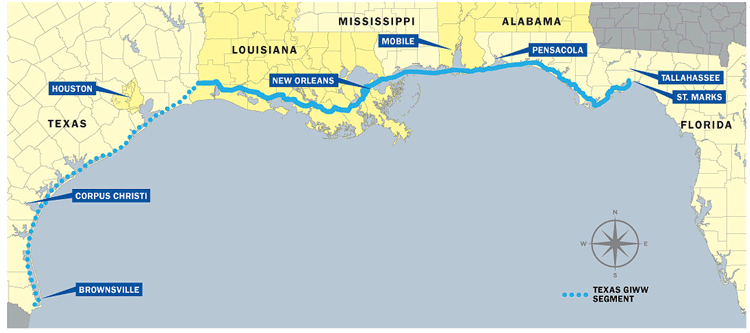

The largest transportation canal in Texas is the state’s section of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW). Built primarily in World War II to transport goods and troops, the GIWW stretches 1,100 miles from Brownsville, Texas, to St. Marks, Florida. The Texas portion is 379 miles long and covers the entire Gulf coastline, connecting the state’s 11 deep-draft ports (Exhibit 1).[1] As a result, it serves as the backbone of nearly all other transportation canals in the state.

Gulf Coast Intracoastal Waterway

While comprising only a third of the entire GIWW, the Texas portion handled 70 percent of the canal’s total traffic in 2018 — about 77.7 million tons.[2] Petroleum or petroleum product transportation represents more than two-thirds of the traffic, or about 54.6 million tons, making the canal vital to Texas’ (and the entire country’s) oil and gas supply chain. This immense capacity equates to the direct creation of 15,000 jobs and $5 billion in direct labor income in the coastal counties.[3] If including the induced and indirect economic impacts, this number increases to 65,000 jobs and $8.7 billion in direct labor income and contributes $31.7 billion to the state’s economic output.[4]

The GIWW is maintained primarily by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; however, the Texas Department of Transportation provides significant support by selecting dredged material disposal sites, evaluating and planning improvements for the waterway, coordinating with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for environmental impact studies, and hosting public meetings on Texas ports and waterways.[5]

Houston Ship Channel

Connecting downtown Houston to the Gulf of Mexico, the 52-mile-long Houston Ship Channel is one of the main reasons Port Houston is the number one port in the U.S. in waterborne tonnage, equating to 3.2 million jobs and $802 billion in national economic value in 2018.[6] For Texas this number is nearly 1.4 million jobs and $339 billion in statewide economic value in 2018, resulting in $5.7 billion in state and local tax revenue.[7] Currently, there are nearly 200 facilities along the channel, including ExxonMobil’s Baytown facility, the 10th largest refinery in the world.[8] These factors make the Houston Ship Channel an important part of Houston and of the global economy.

Currently, the channel is undergoing a $1 billion expansion project, set to be completed by 2025 — this project will widen the channel by 170 feet and deepen some upstream segments to 46.5 feet to accommodate larger ships.[9] This expansion project — critical to sustaining national energy security and domestic manufacturing — is a collaborative effort between the Port of Houston and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers due to its national importance.[10]

Sabine-Neches Waterway

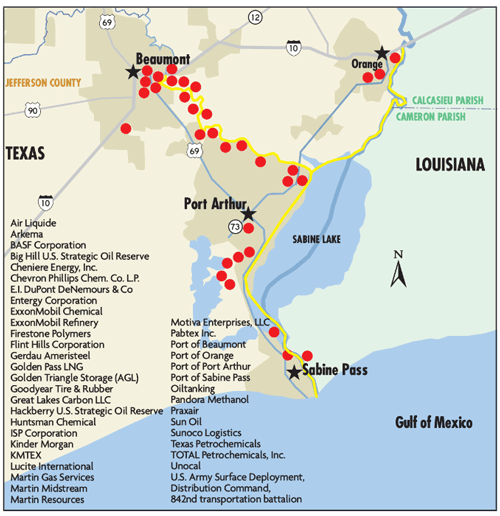

The 57-mile-long Sabine-Neches Waterway is the longest federal deep-draft ship channel on the Texas Gulf Coast and the third largest waterway in the nation by tonnage. It includes two U.S. strategic seaports, the Port of Beaumont and Port of Port Arthur.[11] The waterway serves as “America’s Energy Gateway” and is the largest liquid natural gas (LNG) and crude oil exporter in the U.S.[12] Operations and industry-related sectors supported by the waterway generate nearly 375,000 U.S. jobs, $40 billion in gross domestic product, $23 billion in personal income and $4.2 billion in federal tax revenue.[13]

The Sabine-Neches Waterway also is vital to the U.S. military, as Port of Port Arthur and Port of Beaumont are both home to two of the military’s Strategic Commercial Seaports. The waterway also supports the top refiner of jet fuel in the U.S., which supplies the majority of military jet fuel.[14] Due to the waterway’s national importance, the Sabine-Neches Navigation District and the federal government began the Channel Improvement Project (also called “The Deeping Project”) in 2019 — the waterway’s first major improvements since 1962. The project will deepen the channel from 40 feet to 48 feet and generate massive economic benefits to Southeast Texas, the state of Texas and the U.S. The project will take about seven years to complete.[15] The waterway is maintained through a joint effort by the Sabine-Neches Navigation District and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.[16]

The Sabine-Neches Waterway, like the Houston Ship Channel, connects to the GIWW (Exhibit 2).

Sabine-Neches Waterway: America’s Energy Gateway

Irrigation and Water Supply Canals

Lower Neches Valley Authority Canal System

The Lower Neches Valley Authority (LNVA) manages and protects the fresh water in the Neches River Basin and the Neches-Trinity Coastal Basin, covering the counties of Tyler, Hardin, Liberty, Chambers and Jefferson. The watersheds of the Neches River and its tributaries cover 10,300 square miles and produce 5.6 million acre-feet of water annually at its mouth at Port Arthur, assisted by generous levels of rainfall in the region. LNVA is the non-federal sponsor of Sam Rayburn Reservoir and Lake BA Steinhagen, which are owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Water supply requirements of LNVA are released by the Corps through turbines to generate electricity for area homes and businesses. The water then flows bed and banks down the Neches River through the Big Thicket National Preserve to where it is picked up by LNVA at pump stations that lift the water into a canal distribution system. The distribution system delivers fresh water to eight cites, 26 industries and more than 100 irrigated farms in the region.[17]

The 400-mile LNVA canal system ensures the efficient delivery of the region’s water. The system encompasses about 700 square miles of land, primarily in Jefferson, Liberty and Chambers counties. The system provides continuous delivery of water to the region’s cities, industries and farms, including oil and gas refining complexes and rice farms that are built around the availability of fresh water. The benefit of the canal system is that after the water is initially pumped out of the lower Neches River and Pine Island Bayou, no further pumping is required; all the water is delivered by gravity. The canal system also enhances the area’s biodiversity. The industrial water supply canals have some of the greatest mussel diversity found anywhere in the state, though the freshwater mussels’ potential Endangered Species Act listing could impact the canal system and pose a challenge for LNVA.[18]

Devers Canal System

In addition to canals originating on the Neches River, LNVA operates the Devers Canal System drafting water from the Trinity River in Liberty County. The Devers Canals extend some 200 miles across eastern Liberty and Chambers counties. This canal system is solely used for irrigation but is critical to the agricultural community producing rice and crawfish.

John W. Simmons Gulf Coast Canal System

Starting on an intake canal near the Sabine River around Orange County, the 75-mile-long John W. Simmons Gulf Coast Canal System carries 360 million gallons of water a day to municipal, agricultural and industrial customers in East Texas.[19] It supports petrochemical plants, a pulp and paper mill, a steel plant and an electrical generating station.[20] While this project is smaller in scope than others in the state, it is still a vital tool in its local communities.

Rio Grande Project

The Rio Grande Project is a combination of canals, dams and reservoirs built along the Rio Grande River from Texas to New Mexico.[21] It assists in making 178,000 acres of land in Texas and New Mexico irrigable, along with an additional 25,000 acres in Mexico. About 60 percent of the lands receiving water from the project are in New Mexico, and 40 percent are in Texas.[22] To accomplish this, 141 miles of main canals and 462 miles of smaller canals were built as the main delivery methods for the water stored in the reservoirs.[23]

There are a number of additional canal systems that move water across the state of Texas. The Coastal Water Authority moves water for the city of Houston from the Trinity River to the Lynchburg Reservoir; the San Jacinto River Authority moves water from Lake Houston to the city of Houston and industry; the Gulf Coast Water Authority moves water from the Brazos River to Texas City and Galveston; the Lower Colorado River Authority operates the Garwood and other canal systems for rice irrigation; and in south Texas, there are a number of irrigation districts that take water from the Rio Grande.

Links are correct at the time of publication. The Comptroller's office is not responsible for external websites.

- Texas Department of Transportation, Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Legislative Report (PDF) (Austin, Texas), pp. 3-4, (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Texas Department of Transportation, Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Legislative Report (PDF) (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Texas Department of Transportation, Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Legislative Report (PDF) (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Texas Department of Transportation, Gulf Intracoastal Waterway Legislative Report (PDF) (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Texas Department of Transportation, 2021-2022 Educational Series, Ports and Waterways (PDF) (Austin, Texas, January 2021), pp. 4-5, (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Port Houston, (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Port Houston, “The Economic Impact of the Houston Ship Channel,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Houston Ship Channel Expansion, Project 11, “Project Overview,” (Last visited September 26, 2022); and ExxonMobil, “Baytown Complex,” (PDF) (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Houston Ship Channel Expansion, Project 11, “Project Overview,” (Last visited September 26, 2022); and Jay R. Jordan, “Houston Ship Channel launches $1 billion expansion project,” Houston Chronicle (June 1, 2022), (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Houston Ship Channel Expansion, Project 11, “Project Overview,” (Last visited September 26, 2022) ↳

- Sabine-Neches Navigation District, “About Us,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Sabine-Neches Navigation District, “Improvement Project of National Significance,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Sabine-Neches Navigation District, “Sabine-Neches Waterway: Energy Dominance Starts Here,” (PDF) (June 2020), (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Sabine-Neches Navigation District, “Improvement Project of National Significance,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Sabine-Neches Navigation District, “Deepening Project,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Sabine-Neches Navigation District, “About Us,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Lower Neches Valley Authority, “About,”; and Interview with Scott Hall, General Manager, Lower Neches Valley Authority, July 17, 2022. ↳

- Lower Neches Valley Authority, “About,” (Last visited September 26, 2022); and Interview with Scott Hall, General Manager, Lower Neches Valley Authority, July 17, 2022. ↳

- Sabine River Authority of Texas, “Gulf Coast Canal System,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- Sabine River Authority of Texas, “Gulf Coast Canal System,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation, Rio Grande Project, Historical Perspective of Rio Grande Project (PDF) (El Paso, Texas) (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation, “Rio Grande Project,” (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

- U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation, Rio Grande Project (PDF), by Robert Autobee (1994), p. 3, (Last visited September 26, 2022). ↳

For additional insights, see The 2022 State Water Plan and Innovations in Texas Water Systems, Fiscal Notes, June-July 2022.