Texas Water Tour: Cloud Seeding

Cloud Seeding Snapshot | Print Snapshot (PDF)

Introduction

Water is the lifeblood of our state, and a reliable water supply is vital to the Texas economy and its growing population. According to the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), Texas’ water demands are projected to increase by approximately 9 percent over the next 50 years, while its existing water supplies are projected to decline by approximately 18 percent during that time.[1] It is crucial, therefore, for Texas to secure the water resources necessary to sustain its growth and provide for the future. To help supplement the state’s water supply, some areas are using periodic cloud seeding attempts to increase rainfall.

What is Cloud Seeding?

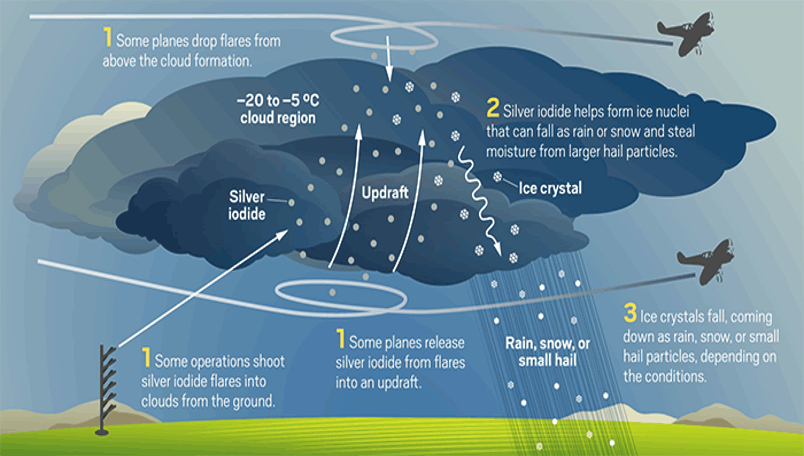

Cloud seeding (also called precipitation enhancement) is a form of weather modification used to stimulate clouds to produce more rain. The process involves using aircraft to spray clouds with small particles that have a structure like ice, such as silver iodide. The particles cause the moisture in the cloud to condense into water droplets until they are heavy enough to fall as rain (Exhibit 1).

How Cloud Seeding Works

Source: Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District

Cloud seeding is not always used to produce rain. Some projects, such as those near ski resorts, attempt cloud seeding to increase snowfall. Other uses include dispersing fog, suppressing hail, or steering a potentially heavy rainstorm away from a populated area. China made headlines in 2008 when it used cloud seeding before the Beijing Olympic games to prevent rain over the roofless 91,000-seat Olympic stadium nicknamed the Bird’s Nest.[2]

Many countries have invested in weather modification technologies, including cloud seeding, in recent years to mitigate water shortages caused by population growth and drought. The United Arab Emirates, for example, has been a leader in exploring this technology within the dry Gulf region, operating a cloud seeding program since 2002. [3]

In the U.S., cloud seeding is increasingly accepted as an effective method of providing relief in drought-stricken states such as Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. Cloud seeding projects in these states often are funded through cost-sharing agreements between state and local governments, but sometimes private parties, such as ranchers or ski resorts, contribute funding.[4]

Cloud Seeding in Texas

Though rain-making efforts had been attempted earlier in the 20th century, serious cloud seeding operations began in Texas during the severe drought of the 1950s. Some of the projects used ground-based generators to dispense agents such as silver iodide, while others featured aircraft that released various seeding materials, including dry ice, into cloud formations.[5]

Most efforts to produce additional rainfall using cloud seeding are found in the western part of Texas during the growing season, but criteria determining where and when to seed vary. The Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District, for example, cited these conditions as necessary for its cloud seeding attempts:

- Dates between April 1 and Sept. 30.

- Cloud bases between 4,000 feet and 12,000 feet.

- Convective clouds (i.e., they must have vertical depth extending beyond the freezing level of the cloud along with sufficient cloud base inflow).[6]

Most cloud seeding programs in Texas operate an average of 25 days to 45 days a year, depending on cloud conditions. An operational day could result in multiple flights with 1.5 hours to 8 hours of total flight time.[7]

The Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation (TDLR) issues licenses and permits for these projects through its Weather Modification Program. The licenses ensure that the cloud seeding projects, most of which have been in operation for 20 years or more, are directed by meteorologists with sufficient training and experience, and the permits designate the areas in which the aircraft may operate.[8]

The regulation of weather modification began with the Texas Weather Modification Act of 1967, which the 60th Legislature enacted to ensure that various methods of modifying the weather do not have adverse effects on clouds or their natural ability to produce rainfall. TDLR’s Weather Modification Program also assists operators in the design of cloud seeding operations and administers federal grants for cloud seeding studies.

In Texas, rainfall enhancement generally is seen as just one of many water management strategies used by water conservation districts, aquifer authorities, county commissions, and other sponsors to ensure there is enough water for future needs.

Between 1997 and 2004, state matching funds totaling about $11.7 million helped these groups purchase the special equipment needed for cloud seeding, such as aircraft and radar systems. The state also contributed another $1.5 million for project assessments. State funding is no longer available for cloud seeding operations, and current cloud seeding projects are funded in total by local sponsors.[9]

The following cloud seeding projects are currently permitted by TDLR.[10]

- South Texas Weather Modification Association (STWMA), based south of San Antonio in Pleasanton, has a target area of nearly 6 million acres stretching from the base of the Edwards Plateau almost to the coastal bend of Texas. As an alliance of the Evergreen Underground Water Conservation District, the Live Oak Underground Water Conservation District, and a county commission, the STWMA operates on a year-round basis.

- The West Texas Weather Modification Association (WTWMA) is based in San Angelo and has a target area of 6.4 million acres between Midland and San Angelo. The WTWMA holds permits for both rain enhancement and hail suppression operations.

- The Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District (PGCD) conducts cloud seeding operations to augment groundwater recharge over the Ogallala Aquifer in its target area of nearly 4.1 million acres in the eastern sector of the Texas Panhandle, which gives it access to cloud systems moving out of Oklahoma.

- The Trans Pecos Weather Modification Association (TPWMA) consists of the Ward County Irrigation District and other political subdivisions within Culberson, Loving, Pecos, Reeves, and Ward counties. Its 5.1-million-acre target area is along and west of the Pecos River. TPWMA’s seeding missions are directed by a meteorologist based in San Angelo, and its aircraft are based at the airports in Pecos, Fort Stockton, and Alpine.

- The Rolling Plains Water Enhancement Project is sponsored by several counties north of Abilene and covers a target area that extends east toward the Red River Valley. Its original target area was 3.5 million acres; however, three additional counties have since been added to the west and southwest to allow for an adequate “buffer” in which aircraft could operate to seed storms moving northeastward into the target area. The seeding aircraft operate from within the multi-county target area.

Cloud seeding is a small part of the TWDB’s 2022 State Water Plan. Included in the “Other Strategies” category as Weather Modification, the plan projects that this strategy will provide about 5,000 acre-feet of water per year for irrigation users by 2070 — about 1 percent of the total recommended strategy supplies in that year.[11]

Cost of Cloud Seeding

The cost of cloud seeding varies greatly depending on factors such as the size of the target area and the type of equipment needed. PGCD, for example, cited aircraft as a major expense. However, because the district now owns its airplanes, the cost of cloud seeding has decreased to 3 cents per acre. [12]

In estimating the economic impacts of cloud seeding, it is necessary to account for both the benefits of additional water over the seeded area and the total costs of the project. For example, crop quality may improve when there is sufficient water available for adequate irrigation. Likewise, when there are more recreational waters in the summer and snow in the winter, tourism increases, which, in turn, supports job growth.

Challenges

One of the challenges in assessing the success of cloud seeding is that it is very difficult to conclusively determine the enhancement of precipitation over a specific area and time. Some studies, however, indicate that cloud seeding is indeed effective. For example, a 2019 report by the World Meteorological Organization cited a study of cloud seeding programs — including in Australia, China, India, Israel, South Africa, Russia, Thailand, and the United States — that found resulting increases in precipitation between 10 percent and 30 percent.[13]

The environmental impact of cloud seeding is often raised as a concern, as the process involves dispersing silver iodide — considered to be a hazardous substance in large quantities — into the atmosphere. Research, however, indicates that cloud seeding has a negligible impact on the water and soil in the target areas. According to TDLR, the amounts of silver detected from rainwater samples collected in Texas were a tiny fraction of what is deemed acceptable by the U. S. Public Health Service. TDLR maintains that no significant environmental impacts have been observed around cloud seeding operations, including those projects that have existed for 30-40 years.[14]

Outlook

Experts point out that cloud seeding is not a cure-all, because it doesn’t solve the systemic causes of drought and can be tricky to implement. And when it is successful, there is no guarantee that it will break a drought nor any certainty that it was the direct cause of any rain that may have fallen.

By itself, therefore, given the state of technology today, cloud seeding can hardly be considered a major source of new water in Texas. However, ongoing research, in Texas and elsewhere, suggests new and better seeding agents and approaches have the potential to expand the population of clouds that can be nudged to yield additional rainfall. Cloud seeding is proving to be effective as one of several tools available to the state that, together, can be coordinated to increase our water resources.

End Notes

Links are correct at the time of publication. The Comptroller's office is not responsible for external websites.

- Texas Water Development Board’s 2022 State Water Plan (PDF) , p. 3. ↳

- MIT Technology Review, Weather Engineering in China ↳

- The Middle East Institute, Looking to the skies: The growing interest in cloud seeding technology in the Gulf ↳

- Yale School of the Environment, Can Cloud Seeding Help Quench the Thirst of the U.S. West? ↳

- Texas Weather Modification Association, History ↳

- Email from Britney Britten, General Manager, Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District, August 4, 2022. ↳

- Email from Britney Britten, General Manager, Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District, August 4, 2022. ↳

- Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation, Weather Modification ↳

- Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation, Weather Modification ↳

- Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation, Harvesting the Texas Skies in 2022 - A Summary of Rain Enhancement Operations in Texas ↳

- Texas Water Development Board, 2022 State Water Plan (PDF) ↳

- Email from Britney Britten, General Manager, Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District, August 4, 2022. ↳

- The Middle East Institute, Looking to the skies: The growing interest in cloud seeding technology in the Gulf ↳

- Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation, 3. How successful is cloud seeding? ↳

For additional insights, see The 2022 State Water Plan and Innovations in Texas Water Systems, Fiscal Notes, June-July 2022.