Supply Chains Rare Earth Elements Supply Chain

Rare Earth Elements Snapshot | Print Snapshot (PDF)

Introduction

Lean, global supply chains can maximize efficiency while helping to build Texas’ trade and economy. But the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that global supply chains must be resilient as well as efficient. To stabilize their supply chains, some industries – particularly those vital to economic or national security -- are making efforts to add redundancy or “reshore” their manufacturing processes.

One less-visible supply chain is that of critical minerals, including the so-called rare earth elements (REEs). While a domestic supply for these materials is not yet established, rapid changes in the nascent national REE industry promise to give Texas a central role.

What are Rare Earths?

The 17 REEs are chemical elements with atomic numbers 57 through 71 (the lanthanides), plus scandium and yttrium. These metals have certain fluorescent, magnetic or conductive properties that make them well-suited for use in high-tech components such as permanent magnets, catalysts, rechargeable batteries, and LED lights and displays (Exhibit 1).[1] The final goods that rely on these components range from smartphones and other consumer electronics, to advanced military weapons and communications systems, to renewable energy technology such as wind turbines and electric vehicles.

| Element | Symbol | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lanthanum | La | Optical glass, nickel-metal-hydride batteries |

| Cerium | Ce | Colored glass (flat-panel displays), automobile catalytic converters, petroleum refining |

| Neodymium | Nd | Permanent magnets |

| Yttrium | Y | Metal alloys, visual displays, lasers, lighting |

Source: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

Note: Oxides of these four rare earth elements are estimated to be most widely imported and used by quantity, according to USGS data.

While the global market for tradeable REEs is thought to be about $3 billion to $5 billion,[2] one estimate of the value-added market for final goods containing REEs is over $1 trillion.[3] Lanthanum, cerium, neodymium and yttrium are estimated to be the most widely used by quantity, according to a 2010 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) analysis of imported metals and REE-containing manufactured goods.[4]

As the global economy continues to become more technologically advanced and sustainable, demand for REEs will grow. Supply chains must keep up. And with substantial rare earth deposits in our state, Texas businesses can help ensure that high-tech goods across the world are partially made with Texas dirt.

Supply Chain

REEs are not truly “rare” — they are found all over the world — but deposits containing economically usable concentrations are less common. Significant sources of REEs include bastnaesite and monazite, mineral ores often containing a mix of rare earths and other elements.[5]

Several physical, magnetic and chemical methods can be used to separate and process the metals. First, the ore containing REEs must be milled and concentrated. Next, the concentrated ore is separated into rare earth oxides (REOs), a higher level of purity at which individual rare earth elements can be measured and traded as commodities.

Finally, REOs are processed into rare earth metals and are ready to be used in the downstream manufacturing of industrial and consumer goods, either on their own or mixed in alloys with other metals.[7]

Mining and processing rare earths can be complex and costly, with serious environmental impacts. But some companies – including at least one here in Texas – are developing innovative systems and practices to mitigate such issues.

China dominates the mining and processing of rare earths. According to the USGS, in 2020 China produced 140,000 metric tons of REO equivalents, or 58.3 percent of the global supply. The next-largest producers were the United States (38,000 metric tons of REO), Myanmar (30,000) and Australia (17,000).[8] While Brazil and Vietnam currently produce low quantities, each has more than 20 million tons of rare earth reserves.

Although China’s share of global REO production has decreased in recent years, the country still possesses most of the world’s capacity to process REOs into usable metals. In 2020, the United States imported 100 percent of its usable rare earth compounds and metals, valued at $110 million that year. Eighty percent of that came from China. Three-quarters of U.S. rare earth imports were used as catalysts, mostly in petroleum refining processes and catalytic converters for vehicles.

Supply Chain Risks and Mitigation

Experts are increasingly concerned about China’s ability to exploit its market status by restricting REE exports for economic or military leverage.

For decades, the country has aggressively built its rare earth mining and processing industrial base, with production increasing by an average of 40 percent per year between 1978 and 1995.[9] During that time, China effectively shut out the rest of the world market for critical minerals by subsidizing the industry to discourage competition, taking advantage of lax environmental and labor laws, and restricting foreign investment.[10]

In 2010, the country controlled a peak 97 percent of the supply of rare earths.[11] Then, during a diplomatic dispute with Japan, China abruptly slashed REE exports by 37 percent, and global prices jumped sevenfold.[12] The market did not stabilize until a resolution between China and its trading partners was negotiated by the World Trade Organization in 2014.

More recently, U.S. rare earth imports from China were temporarily hit with 25 percent tariffs as part of the 2018-2019 trade skirmish between China and the United States. Due to concerns about short supply, the U.S. did not reciprocate.[13]

Diversification

Soon after the 2010 Chinese embargo, rare earth importers such as Japan, Australia and the United States began to investigate diversifying their supply chains. Now, the REE landscape around the world is rapidly evolving as new mines and processing facilities come online.

U.S. Government Initiatives

With the extensive use of REEs in critical weapons, defense and communication systems, U.S. policymakers are particularly concerned about the national security implications of dependence on Chinese metals. A comprehensive interagency effort to build a domestic, vertically integrated REE supply chain is underway, including the departments of Defense, Energy, Interior and State.

A significant development was presidential Executive Order 13817, signed on Dec. 20, 2017. The order directed the Department of Commerce to offer strategies to reduce U.S. reliance on critical minerals, increase recycling and substitutions, improve trade relationships in critical minerals, and develop better mapping and permitting processes. The department’s report was released on June 4, 2019, establishing a federal strategy of 24 goals and 61 recommendations built on a framework of six calls to action:

- Advance transformational research, development and deployment across critical mineral supply chains.

- Strengthen America’s critical mineral supply chains and defense industrial base.

- Enhance international trade and cooperation related to critical minerals.

- Improve understanding of domestic critical mineral resources.

- Improve access to domestic critical mineral resources on federal lands and federal permitting timeframes.

- Grow the American critical minerals workforce.

Much already has been accomplished. In 2018, the U.S. Department of the Interior designated 35 specific minerals as critical to economic and national security, including the 17 REEs.[14] In July 2019, a set of presidential determinations authorized the Department of Defense (DoD) to use Defense Production Act (DPA) Title III Authority to forge agreements with businesses to strengthen the domestic rare earths supply chain.[15]

Also in 2019, the USGS, with state and local partners, began the Earth Mapping Resource Initiative (Earth MRI) to conduct geophysical and lidar surveys aimed toward collecting more data on rare earth deposits and locating new ones.[16] Additionally, the coronavirus relief bill signed at the end of 2020 directed $800 million for domestic investment in rare earth mining and processing as well as other goals specified in the 2019 Commerce report.[17]

Strengthening the rare earth supply chain is a bipartisan effort, and the Biden administration also is working to advance these strategic goals.

Domestic Sources

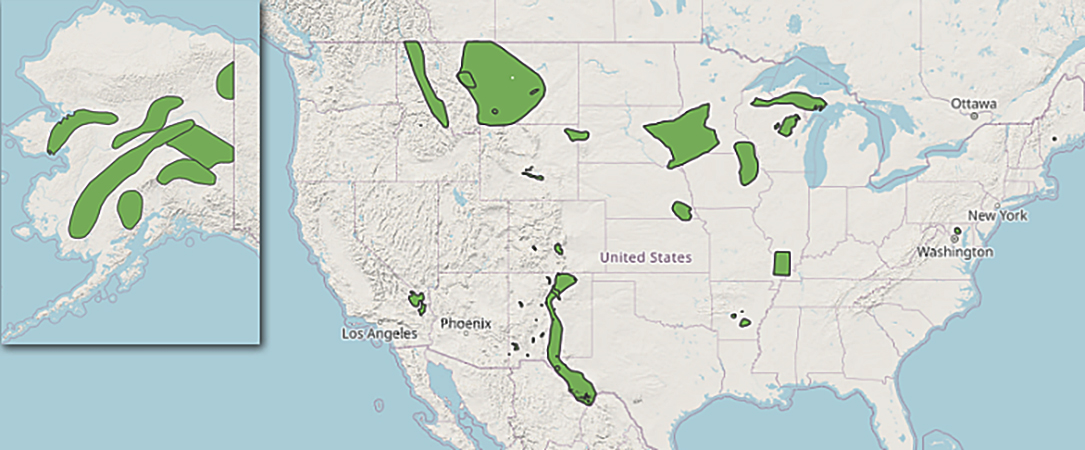

Rare earth deposits have been found in at least 19 states. A number of projects to build domestic mining and processing capacity are ongoing, some with significant federal government backing.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s Earth Magnetic Resonance Imaging project is currently investigating and mapping a number of areas in the United States where rare earth elements and other critical minerals are likely to be found. Areas under scrutiny for rare earth elements include sites in Texas, New Mexico, Alaska, Wyoming and others.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s Earth Magnetic Resonance Imaging project has identified the stretch of West Texas from El Paso to Big Bend as geologically suitable for the presence of rare earth elements. The Round Top deposit in Sierra Blanca is one proven site within this area and will be mined commercially for a number of rare earth elements starting in 2023.

Source: USGS Earth Mapping Resource Initiative

Mountain Pass (MP) Materials, whose California operation is the only working U.S. rare earth mine and is currently the biggest source of rare earths outside China, received a $9.6 million DPA grant in November 2020.[18] Closed for years, the MP Materials mine reopened in 2017 and will soon begin on-site separation and processing of REEs. By 2025, the company says it hopes to restore an entire supply chain to U.S. shores, from “mine to magnet.”[19]

A former uranium mine on Bokan Mountain, Alaska, is also a promising source for rare earths; leasing company Ucore Rare Metals Inc., believes the mine could yield 375 metric tons of high-grade REEs per day for approximately 11 years.[20] The Bear Lodge deposit in Wyoming is thought to contain enough REOs to produce about 550,000 tons over the 38-year life of a proposed mine.[21] And a new, joint effort[22] between Canadian company Neo and Energy Fuels Inc., a U.S. uranium mining company, plans to mine monazite in Georgia, begin processing it for REEs in Utah and ship it to Neo’s facility in Estonia for the REE carbonates to be separated.[23]

Extraction Technology

DoD also is investing in research to extract rare earths from ore more efficiently and economically. For example, the department granted $1.8 million to a Ucore subsidiary to help it develop RapidSX, a new and more efficient solvent extraction process used to produce REO.[24]

Other extraction possibilities being investigated include laser ablation, ultrasound, chromatography and electrodialysis, in addition to other, more efficient chemical processes that could make certain mineral deposits more economically viable.[25] Research also is being conducted into extracting REEs from coal ash and other coal-mining byproducts.[26]

Recycling and Reuse

Recycling of REEs is still in its infancy. While REEs could potentially be recovered and reused from LEDs, magnets, fluorescent light bulbs and rechargeable batteries, such recycling is limited and not economical. The European Union’s REE4EU is one example of an innovative program aiming to retrieve and recycle rare-earth permanent magnets to be used in hybrid vehicles and wind turbine generators.[27] Urban Mining Co., based in San Marcos, Texas, is conducting REE recycling on a pilot, small-scale basis.

Challenges

Efforts to rebuild U.S. REE supply chains must contend with a number of challenges. Development of rare earth mines and processing facilities is beset by long permitting processes and complex regulations. At many sites, much of the waste can be environmentally hazardous and requires mitigation. And the high capital costs of mining, combined with the low market prices of most REOs, can make the process uneconomical.[28]

Workforce development presents yet another obstacle, as the mining industry works to attract skilled technicians as well as workers with next-generation technology skills in AI, automation and data analytics.[29] Finally, maintaining high levels of physical security and cybersecurity is of great importance because of the economic and national security implications of changes to the global REE status quo.

Rare Earths in Texas

USA Rare Earth (Round Top, Sierra Blanca)

Texas has an important role to play in building the domestic REE supply chain. The Texas-built F-35 fighter jet, for instance, uses 920 pounds of rare earths, and the state is a major location for high-tech, clean energy and electric vehicle manufacturing — primary users of REEs. While production of rare earths in Texas has not yet begun, our state contains one of the largest domestic rare earth deposits, and work is well underway to bring those resources to market.

Starting in 2023, USA Rare Earth will be mining 950 acres of state land at the Round Top deposit in Sierra Blanca, Texas.[30] The mine is likely to yield 16 of the 17 rare earths and more than 300,000 metric tons of REO.[31] The company intends to process ores on site and eventually create a fully domestic supply chain of rare earth magnets — consolidating nearly every aspect of the manufacturing process within the nation’s borders. The operation is expected to meet 17 percent of projected U.S. demand with $140 million in annual sales.[32]

According to the company, the Round Top project is likely to produce nearly $400 million in economic impact, plus another $200 million from magnet production. Once up and running, USA Rare Earth expects its facility to provide between 130 and 195 direct, full-time permanent jobs with above-average salaries. And the company plans to use a proprietary process to reduce the environmental impacts that similar operations experience elsewhere.

Other Texas Activity

In February, DoD announced a $30 million DPA Title III agreement with Australian company Lynas Rare Earths, the largest producer outside China, to begin separating rare earths in Hondo, Texas, in partnership with San Antonio-based Blue Line Corp.[33]

Meanwhile, Urban Mining Co. inked an $860,000 agreement with the DoD to support its efforts to recycle REEs from electronic waste and produce new permanent magnets.[34]

Looking Ahead

As the effects from the pandemic and other crises continue, many industries are facing uncertainties in their supply chains and are looking to bring them closer to home. But unlike other industries, a U.S.-based rare earth supply chain must be built from (literally) the ground up. As development rapidly moves forward on a number of projects, Texas and the United States soon will begin to see benefits from a secure, domestic REE supply to meet the ever-increasing demand.

Endnotes

Links are correct at the time of publication. The Comptroller's office is not responsible for external websites.

- Science History Institute, “The History and Future of Rare Earth Elements.” ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Energy, (“Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper,” (PDF) p. 9. ↳

- National Energy Technology Laboratory, “Critical Minerals Sustainability Program,” ↳

- U.S. Geological Survey, “Preliminary Estimates of the Quantities of Rare-Earth Elements Contained in Selected Products and in Imports of Semimanufactured Products to the United States, 2010” (PDF) ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Energy, “Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper,” (PDF) ↳

- Congressional Research Service, “An Overview of Rare Earth Elements and Related Issues for Congress,” (PDF) Nov. 24, 2020, p. 7. ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Energy, “Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper.” (PDF) ↳

- U.S. Geological Survey, “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2021” (PDF). ↳

- Science History Institute, “The History and Future of Rare Earth Elements.” ↳

- Center for Strategic and International Studies China Power Project, “Does China Pose a Threat to Global Rare Earth Supply Chains?” ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Defense, “Assessing and Strengthening the Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency of the United States,” (PDF) Sept. 2018, p. 36. ↳

- “Amid Tension, China Blocks Vital Exports to Japan,” New York Times, Sept. 22, 2010. ↳

- Center for Strategic and International Studies China Power Project, “Does China Pose a Threat to Global Rare Earth Supply Chains?” ↳

- U.S. Geological Survey, “Interior Releases 2018’s Final List of 35 Minerals Deemed Critical to U.S. National Security and the Economy,” May 18, 2018. ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Defense Industrial Policy, “Defense Production Act Title III Presidential Determinations to Strengthen the Domestic Industrial Base and Supply Chain for Rare Earth Elements,” July 23, 2019. ↳

- Congressional Research Service, “An Overview of Rare Earth Elements and Related Issues for Congress,” (PDF) Nov. 24, 2020, p. 4. ↳

- “Miners praise U.S. spending bill that funds rare earths programs,” Reuters, Dec. 30, 2020. ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Defense, “DOD Announces Rare Earth Element Awards to Strengthen Domestic Industrial Base,” Nov. 17, 2020. ↳

- “The new U.S. plan to rival China and end cornering of market in rare earth metals,” CNBC, Apr. 17, 2021. ↳

- Congressional Research Service, “An Overview of Rare Earth Elements and Related Issues for Congress,” (PDF) p.5. ↳

- Congressional Research Service, “An Overview of Rare Earth Elements and Related Issues for Congress,” (PDF) p.5. ↳

- “A new US-Europe rare earths supply chain is using a ‘very Chinese model’ to counter China,” Quartz, July 12, 2021. ↳

- “Energy Fuels’ first shipment creates US-Europe rare earths supply chain,” Mining.com, July 9, 2021. ↳

- Congressional Research Service, “An Overview of Rare Earth Elements and Related Issues for Congress,” (PDF) p.7. ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Energy, “Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper,” (PDF) p. 11. ↳

- National Energy Technology Laboratory, “Improved Rare Earth Element Extraction Method from Coal Ash,” Nov. 16, 2020. ↳

- European Commission, “Recycled permanent magnets provide a source for rare earth elements.” ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Energy, “Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper,” (PDF) p. 9. ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Energy, “Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper,” (PDF) p. 10. ↳

- “The U.S. Needs China For Rare Earth Minerals? Not For Long, Thanks To This Mountain,” Forbes, Apr. 7, 2020. ↳

- Congressional Research Service, “An Overview of Rare Earth Elements and Related Issues for Congress,” (PDF) p.6. ↳

- “The U.S. Needs China For Rare Earth Minerals? Not For Long, Thanks To This Mountain,” Forbes, Apr. 7, 2020. ↳

- U.S. Dept. of Defense, “DOD Announces Rare Earth Element Awards to Strengthen Domestic Industrial Base,” Nov. 17, 2020. ↳

- “Urban Mining Company’s Rare Earths Recycling Helps Us Tackle Chinese Dominance,” Forbes, June 11, 2020. ↳

Questions?

If you have any questions or concerns regarding the material on this page, please contact the Comptroller’s Data Analysis and Transparency Division.