Fentanyl Flowing into Texas Law enforcement targets cartels, gangs to squeeze supply

A 1,254-mile line — the length of the Texas-Mexico border — has been drawn and along it, illicit fentanyl is seeping into Texas and claiming lives on an unprecedented scale.

Bridge of the Americas Port of Entry, El Paso, Texas, courtesy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Fifty times more powerful than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, fentanyl can be prescribed as a painkiller or anesthetic. But used illegally, it was linked to almost 1,700 fatal overdoses in Texas in 2021. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) recently reported that its lab testing last year revealed six out of 10 fentanyl-laced prescription pills contain a potentially lethal dose of fentanyl — up from four out of 10 in 2021.

Since March 2021, the combined efforts of Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) troopers, criminal investigators and intelligence specialists dedicated to border operations have led to the seizures of more than 342 million lethal doses of fentanyl, according to the governor’s office.

This mobilization complements ongoing efforts by multiple law enforcement agencies at both federal and local levels to disrupt the supply of illicit fentanyl into Texas. But how it gets across the border, how it is distributed and how it claims lives create ongoing challenges.

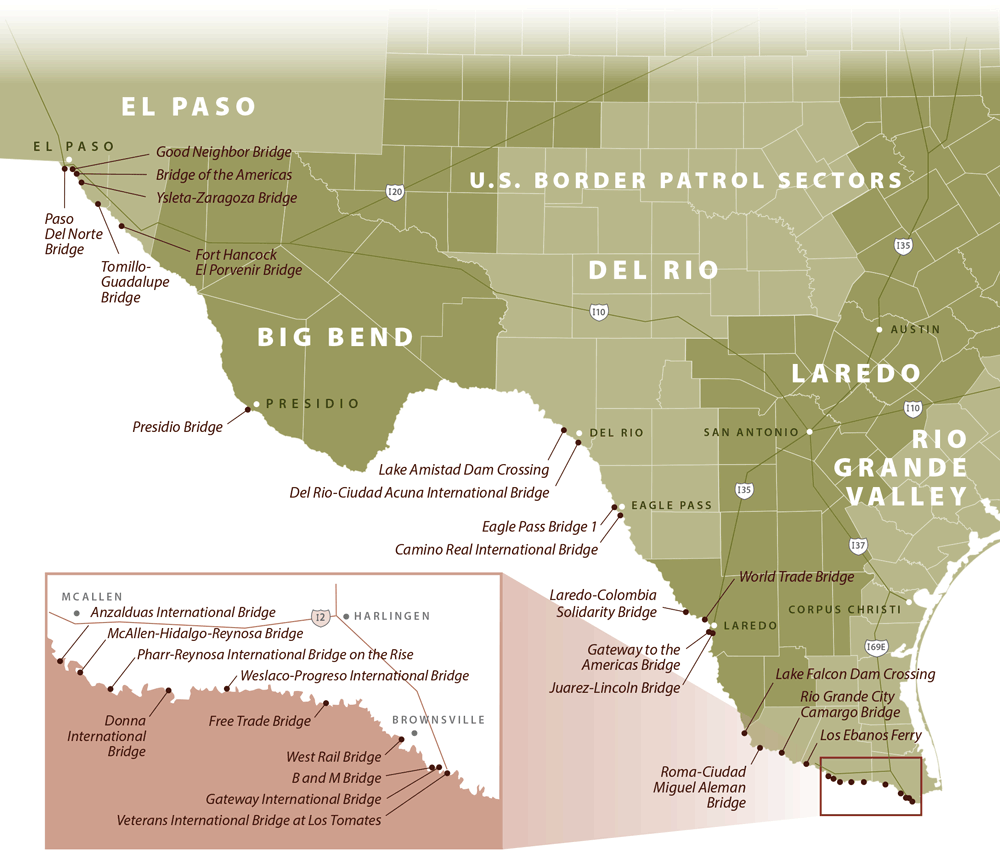

EXHIBIT 1: TEXAS-MEXICO BORDER CROSSINGS AND U.S. BORDER PATROL SECTORS

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) checks for contraband such as illicit fentanyl in five Texas sectors that include 29 international bridges and crossings on the Texas-Mexico border.

Sources: CBP; Texas Department of Transportation

Lost in the Shuffle

Texas’ shared border with Mexico is just one avenue for fentanyl trafficking, due in part to its accessibility. It’s a border joined by 29 international bridges and border crossings (Exhibit 1). In 2021, nearly 43 million personal vehicles, 4.87 million commercial trucks, 51,990 buses and 9,023 trains crossed the border legally, according to U.S. Bureau of Transportation data. In the same year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported more than 1.23 million enforcement encounters in response to illegal crossings on the Texas-Mexico border, including 5,541 drug seizure events.

The DEA has worked with partner agencies to identify and arrest members of drug trafficking networks around the world, but it has named the Mexico-based Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel as the major suppliers of fentanyl in the U.S. Mexican cartels primarily use personally owned vehicles, rental vehicles and trucks/tractor trailers via interstates to smuggle illicit fentanyl and other illegal narcotics into the U.S., while couriers sneak it into the U.S. on commercial airlines, the DEA states.

Other smuggling techniques involve stashing drugs and other contraband in vehicles’ tires, firewalls, gas tanks, after-market compartments and natural voids, but most often, smugglers carry drugs in a body cavity or strap them onto their bodies, CBP’s El Paso Port Director Ray Provencio says.

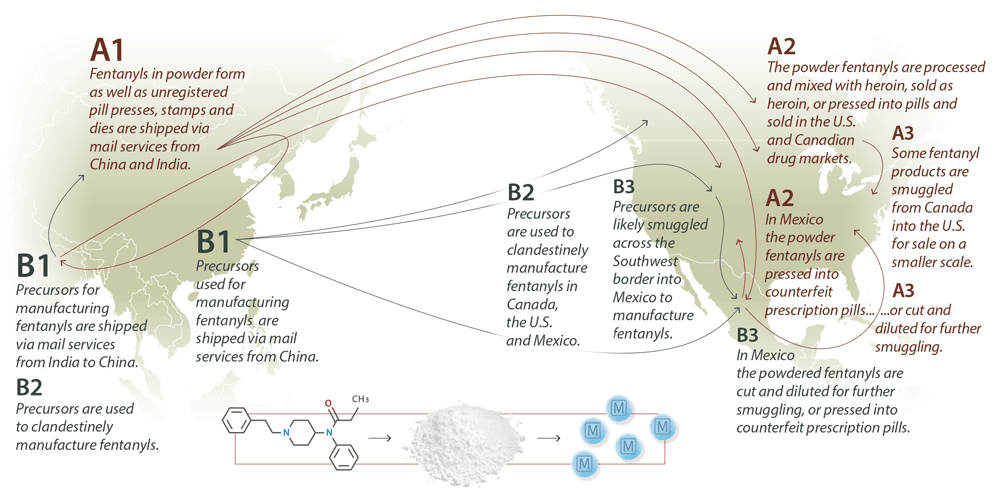

Beyond U.S. borders, fentanyl’s supply chain spans additional miles of ocean and international borders with criminals hungering for profit and law enforcement agencies united in deterrence. Traffickers may adapt their operations, challenging enforcement efforts. For example, China and India drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) and nationals initially supplied their partners in Mexico with fentanyl. After China enacted tougher regulations against fentanyl and its analogues in 2019, the criminal organizations in that country shifted operations to India where fentanyl components were not controlled at the time. Since then, India has also brought these substances under national control.

Stymied by their national governments, these DTOs began exporting precursors — the chemical building blocks used in the early stages of fentanyl production (Exhibit 2).

EXHIBIT 2: FLOW OF FENTANYL INTO THE U.S.

The flow of illicit fentanyl into the U.S. originates in China and India with creation of powders (A) and precursors (B) that are shipped to North America, primarily to Mexico where cartels complete manufacturing before smuggling pills or diluted powder across the Southwest border.

Source: DEA

In Texas, the governor’s office has established several measures aimed at curtailing fentanyl trafficking and building awareness. An executive order designated the two Mexican drug cartels mentioned previously as terrorist organizations and established a Mexican Cartel Division within the Texas Fusion Center, a DPS intelligence division facility that collaborates with federal, state, regional and local law enforcement and collects homeland security information and incident reporting. The recent surge of opioid-related deaths prompted lawmakers to approve and Gov. Greg Abbott to sign Senate Bill 768 in June 2021 to make the manufacture or delivery of fentanyl a criminal offense.

Gov. Abbott also launched the One Pill Kills campaign in October 2022 to raise awareness about deadly fentanyl.

A Deadly Deceit

Deception is one of illicit fentanyl’s most lethal qualities, its threat concealed by its many guises.

DTOs mass produce fake pills to resemble other Schedule II prescription opioids such as OxyContin®, Percocet® and Vicodin®; depressants like Xanax®; or stimulants such as Adderall®, DPS Seized Drugs System Trainer Jennifer Hatch says. These counterfeit pills can contain fentanyl or methamphetamine.

Hatch explains that while lab instrument and color tests quickly detect the difference between real and fake, the difference is often imperceptible to the naked eye.

“We are seeing these [counterfeit pills] in the lab every day, and a lot of times they trick us,” she says. “[Criminals] are becoming more inventive in what they are putting out there. There are so many ways to synthesize it.”

Additionally, fentanyl is often mixed with heroin or methamphetamine, with buyers unaware of its presence — leading victims’ families to say those they lost died of poisonings and not of overdoses.

Appearance is not the only tool employed by drug traffickers to push their product. Using social media and dark web e-commerce platforms and accepting cryptocurrency as payment, cartels and other criminal organizations prey on the public’s trust in legal medications to slip these tiny, yet lethal, doses of fentanyl into harmful mixtures of master counterfeits.

“The cartels are starting to use [online] marketing to drive addiction and gain profit,” DPS Lt. Christopher Olivarez says. “They couldn’t care less who they kill, who they hurt, what lives they destroy. It does not matter to them.”

Deterrence in the Trenches

Of the 29 border crossings and international bridges on the Texas-Mexico border, the Port of El Paso stands out for its numerous points of entry. Provencio heads operations and enforcement activities at 53 lanes at the Bridge of the Americas, Paso Del Norte crossing and Stanton Street Port of Entry’s Secure Electronic Network for Travelers Rapid Inspection (SENTRI) points of entry. The port’s other points of entry include two rail crossings and an import facility with six commercial vehicle lanes as well as CBP operations at the El Paso International Airport.

“It’s one of the most complex ports of entry within the nation, more specifically on the Southwest border,” says Provencio, who oversees a range of 750 to 1,000 CBP officers, agriculture specialists, canine enforcement officers, support personnel and others at these locations.

The bulk of fentanyl seizures in CBP’s El Paso sector, which includes far West Texas and all of New Mexico, occurs at points of entry in the El Paso metro area, according to Provencio. The El Paso port gathers intelligence updates, analytics, targeted information from confidential sources, previous travel patterns and data from officer-traveler interactions. These sources support a layered enforcement approach incorporating officers and canines that detect narcotics.

Anti-narcotics is just one of the port’s five border security missions, which range from national security and anti-terrorism to lawful trade and travel.

“We have encountered a significant shift in narcotics,” Provencio says. “We are seeing a lot more of the harder narcotics, specifically fentanyl. Someone can try to bring in such a small amount of fentanyl, and it has such a huge value on the (black) market.”

CBP’s totals for both the number and weight of fentanyl seizures along the Texas-Mexico border have escalated in recent years, increasing from 14 events in 2019 to 195 in 2022 (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: U.S. CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION TEXAS FENTANYL SEIZURES, FISCAL 2019-2022

Since 2019, U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s seizures of illicit fentanyl at the Texas-Mexico border have risen significantly both in number of events and weight.

Source: CBP

| Fiscal Year | Fentanyl Seizure Events | Fentanyl Seizure Weight |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 14 | 107 lbs |

| 2020 | 45 | 126 lbs |

| 2021 | 135 | 1100 lbs |

| 2022 | 195 | 692 lbs |

CBP seized 107 pounds of fentanyl in 2019 and 692 pounds in 2022. The El Paso Field Office alone recorded an increase of 936 percent: from 36 pounds of fentanyl seized in fiscal 2020 to 373 pounds seized in fiscal 2021.

“It’s a heightened threat not just along the border community but also among the entire U.S.,” Provencio stresses. “Our frontline is out there doing everything they can to mitigate that threat or prevent it altogether.”

Despite law enforcement’s best efforts to halt the flow, the cartels are formidable adversaries, relentlessly pumping fentanyl into Texas, the U.S. and beyond. Both Provencio and Olivarez, who is based in Del Rio, say collaboration among federal, state and local agencies is vital in the attempt to intercept the flow of fentanyl before it reaches distributors in Texas’ interior.

Last Mile Distribution

Part of Gov. Abbott’s September 2022 Executive Order instructed DPS to stop gangs in Texas that support cartel drug operations.

Mexican cartels form business partnerships with transnational gangs, U.S.-based street gangs and prison gangs, according to the DEA. With the cooperation and participation of local street gangs, the cartels deliver fentanyl and other drugs to user markets that they manage or influence in the U.S. through transportation routes and distribution cells.

Realizing the need to share intelligence and resources at the local level, nine Texas Anti-Gang (TAG) Centers bring together local, county and state law enforcement agencies in collaboration to mitigate gang threats. In recent years, newer TAGs in Tyler, Waco and Laredo joined existing centers in El Paso, Houston, Lubbock, Irving, McAllen and San Antonio.

Houston TAG Administrator George Rhyne says that center investigates the “worst of the worst” individuals in Houston, Harris County and neighboring counties in one of the most active areas of the state for gangs. These gangs are constantly developing new tactics, such as dark web advertisements, to get fentanyl into the hands of users while eluding detection, Rhyne says.

“There are several mechanisms that we have found recently that criminal street gangs and individuals involved in narcotics trafficking — especially in fentanyl and ecstasy — are using to get them on the street,” he says.

Stopping the Flow — and Loss of Life

Fentanyl-related deaths are spreading through schools, workplaces and other social institutions at an alarming rate, as evidenced by the rising number of overdoses linked to the drug. Many Texans dying from suspected fentanyl overdoses are unaware of the poison inside the illicit pills they are ingesting.

Data from the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) show a steadily increasing and concerning trend among Texans: 210 fentanyl-related deaths in 2018, 317 in 2019 and 886 in 2020, with provisional data of 1,612 deaths in 2021. For 2022, DSHS reported provisional data for 1,428 fentanyl-related deaths through Oct. 31. Nationally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 66 percent of drug deaths in 2021 were related to synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

To stem the flow of fentanyl and its related fatalities, our state’s chances hinge on collaboration and funding. Texas is meeting the challenge head-on, aided by the formation of the Opioid Abatement Fund Council and an anticipated $1.6 billion over 18 years from opioid settlement agreements, but waves of illicit fentanyl continue to slip past defenses and take lives mercilessly. FN

The Opioid Abatement Fund Council is administratively attached to the Comptroller’s office. Find details about it and other agency initiatives related to the economy or state finances on the programs section of our website.