Innovations in Texas Water Systems Wastewater Not Wasting Away in Texas Cities

Sewage is not waste but a water source in Texas, thanks to innovative thinking. Across the state, the increasing demand for water and drought preparations are driving innovation to reduce demand and increase supply. The solutions are as diverse as Texas, and every aspect of its water system is being evaluated. The motivation is clear: The state’s economy from oil and gas to agriculture and manufacturing, along with life in every Texas town and city, depends on clean and reliable sources of water.

Though not the most appealing, wastewater is reliable, and for a price, it can be cleaned and become a source of its own. In 2020, wastewater reuse made up 7.2 percent of new water supplies in Texas. By 2070, the State Water Plan predicts that reuse will make up 15.1 percent of new water supplies and surpass groundwater as a source of new supplies (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: NEW WATER IN STATE WATER PLAN – PERCENT SHARE BY WATER RESOURCE

| Sources | 2020 | 2070 |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in Demand* | 50.9 | 30.9 |

| Surface Water | 24.2 | 37 |

| Groundwater | 17.6 | 14.5 |

| Reuse | 7.2 | 15.1 |

| Seawater | 0.2 | 2.5 |

*Reduction in demand is projected to come from agricultural, municipal and other conservation efforts.

Source: TWDB, 2022 SWP interactive website

A Brief Texas History of Water Innovations

Texas has a long history of direct and indirect water reuse projects. The wastewater from toilets and showers in Fort Worth and Dallas is treated to meet all federal and state standards before being released into the Trinity River to augment the water supply of Houston.

As far back as 1949, Odessa started to reuse the effluent (PDF) (i.e., the treated outflow from the sewage treatment plant) from a wastewater treatment plant. Now Odessa and Midland sell wastewater for use in fracking oil and gas wells, local irrigation and industrial processes.

In 2009, the North Texas Municipal Water District started indirect wastewater reuse with an 1,840-acre engineered wetland to filter and clean the heavy effluent flows of the Trinity River’s East Fork before sending them to a treatment plant.

In 2013, Big Spring started directly augmenting its freshwater supplies with highly treated water from its sewage treatment plant. Wichita Falls did the same in 2018. El Paso, which has been mixing treated effluent with its aquifer water since 1985, is also planning to directly augment its water supply with highly treated sewage.

On-site water reuse is the next generation. In 2020, the Wimberly School District built Blue Hole Primary School and included in its design the mechanisms to harvest rainwater, air conditioning condensation and grey water (wastewater from showers, baths, sinks and washing machines) to provide water for toilets, landscaping and fire suppression.

Innovation for Water Diversification

“The easy water is gone, or soon to be gone,” says Robert Mace, executive director and chief water policy officer for The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University.

Mace, who was the deputy executive administrator for the Water Science & Conservation Office at the Texas Water Development Board before joining The Meadows Center, believes demand for water could eventually lead cities in Central Texas to fund projects near the Gulf to turn seawater into drinking water and transport that water through pipelines, but he says planners first will work to make existing systems more efficient.

One of the latest examples in this trend is the 198,000-square-foot Austin Central Library, which has reduced its potable water use by 85 percent by capturing rainwater and air conditioning condensate and tapping into the city’s purple pipe network. (Purple is the standard color of pipes across the U.S. that carry recycled water.)

The purple pipe distributes treated effluent, primarily for irrigation, but the water is clean enough for non-potable uses like flushing toilets or manufacturing.

In San Antonio, Credit Human, a credit union, has set the bar higher. The company says its new 200,000-square-foot office building has reduced its potable water use by 97 percent using San Antonio’s purple pipe network, efficient fixtures and a geothermal heating and cooling system. As a result, Credit Human reports its water bills are about 80 percent lower than for its previous building.

Reuse in Action

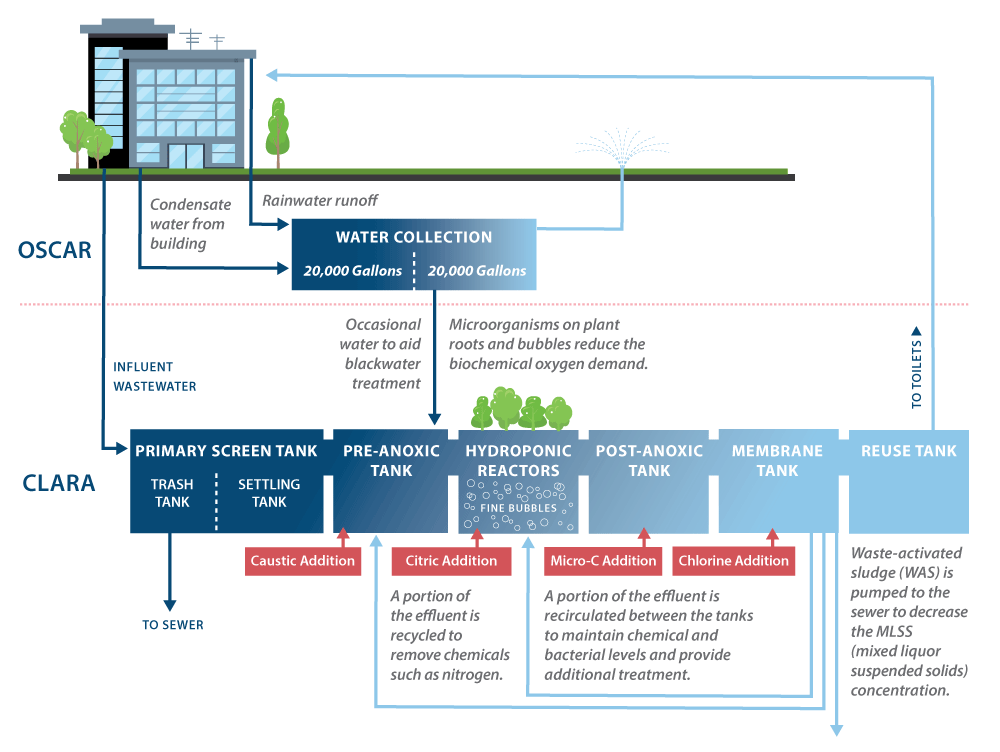

In June, the city of Austin celebrated a rain and condensate catchment system along with a mini sewage treatment plant at the entrance to the city’s new Permitting and Development Center. The catchment system is named OSCAR (short for “on-site collection and reuse system”); the treatment plant, CLARA (“closed-loop advanced reclaimed assembly”).

By catching rainwater, collecting air conditioning condensate and treating sewage on-site for irrigation and non-potable uses like flushing toilets, the city estimates OSCAR and CLARA will reduce potable water demand for the 260,000-square-foot building by 75 percent, saving the city more than 1 million gallons of water each year (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: THE OSCAR AND CLARA SYSTEMS

Source: City of Austin, Onsite Water Reuse Program

OSCAR and CLARA have been operating since May 2022 and are not subtle. Interpretive displays surround the two systems and flank the entrance to the permitting building where every commercial developer is now asked to consider on-site water reuse. For any new building in Austin larger than 250,000 square feet, on-site water reuse will be a requirement by 2023.

“It’s a paradigm shift,” says Katherine Jashinski, the supervising engineer for Austin’s Onsite Water Reuse Program. “We have moved beyond the days of teaching little kids to turn off the water while brushing their teeth.”

Instead of individual actions to conserve water, which still are promoted and important, the focus is on rethinking the entire water system, she says.

CLARA cost $1.7 million, and OSCAR came in at $625,000. Jashinski says the financial return on such systems — if only current water rates are considered — can take from 10 to 40 years. But the higher water demand and treatment costs of the future are what she and the city of Austin are concerned about and what make the projects attractive now.

Currently, the city will pay up to $500,000 per water reuse project to offset costs. According to an initial assessment, in which Jashinski played a role, property owners who upgrade their buildings with water reuse and energy-efficient measures can utilize financing in partnership with local governments to save money from the onset of large developments. The programs enable owners to lower their operating costs and use the savings to pay for water reuse and energy-efficient upgrades over a period of 20 years or more, with little to no capital outlay.

The Big Picture

“There is no such thing as wastewater anymore,” says Anne Kenny Hayden, a spokesperson for the San Antonio Water System (SAWS).

Wastewater is, indeed, a growing water source in the Texas State Water Plan, as Exhibit 3 shows, while surface water and groundwater are shrinking.

Exhibit 3: TEXAS PROJECTED ANNUAL EXISTING WATER SUPPLY (ACRE-FEET)

Note: Does not reflect some portions of existing supplies that are associated with purely saline water sources such as untreated seawater.

Source: TWDB, 2022 SWP interactive website

SAWS has offered rebates and focused on conservation to meet water demand for decades. It has one of the largest purple pipe networks in the country that reuses treated effluent to keep San Antonio’s golf courses green, the River Walk’s river flowing and the Toyota truck plant operating. The city’s system also has diversified its water sources by desalinating brackish groundwater, using underground sand formations as reservoirs and building pipelines. It participates in a plan that pays farmers to forgo irrigating crops in dry years to help maintain higher levels in the Edwards Aquifer, the primary water source for an eight-county region that includes San Antonio.

Now Hayden says the utility is focusing on customers by rolling out the largest smart meter installation in the country.

SAWS Vice President of Water Resources & Governmental Relations Donovan Burton says the big water innovation in using smart meters is the ability to make consumers a direct partner in water planning by giving them real-time data that show the actual cost of watering a lawn.

“That allows them to drive the conversation,” he says.

Burton sees this broader incorporation of diverse stakeholders as the future of water planning.

He points to Mitchell Lake on San Antonio’s south side as an example. It was part of a sewage treatment plant until 1987 and is now an internationally recognized birding destination, hosting 350 species and managed by the Audubon Society. However, after 1987, nutrients below the shallow waters of the lake caused harmful algae blooms, which then flowed into the Medina River during heavy rain events.

The simple solution was $200 million to dredge the sediments, Burton says. This would have destroyed the bird habitat and the locally loved and internationally recognized facility.

SAWS instead went to work and consulted with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the Environmental Protection Agency to find an alternative. The solution was a $70 million to $90 million project to build additional wetlands to filter the runoff. In the process, SAWS created a more diverse habitat for the birds and a bigger birding center and forged stronger partnerships with the National Audubon Society and the city of San Antonio.

“It’s more complex to break down the silos,” Burton says, “but it adds so much more to the quality of the project and the community benefits.”

Broadening the conversation is where the bigger value of projects like the Mitchell Lake wetlands and CLARA and OSCAR come into play, says Amy Hardberger, Texas Tech University George W. McCleskey professor of water law and director of the Center for Water Law and Policy. Hardberger also is a SAWS board member.

“We have a tendency to see this innovative project and say, ‘Oh, we should do that,’” she says. “All these innovative projects are important because they advance the conversation, but we have to get away from this silver bullet mentality, that desal[ination] will save us, or rainwater capture will save us.”

The reality, Hardberger says, is that Texas is too diverse for any one project or innovation to solve all the challenges. It will require a combination of different types of projects and thinking about water.

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” she says. “But once it is invented, you don’t have to wait for necessity. We can do this now.” FN

Learn more about water conservation standards (PDF) for designing state buildings and facilities of higher education.