The Thriving Texas Dairy Industry Texas Dairy Farms Milk Success for Growth

When people think about Texas cattle, they usually imagine longhorns, cowboys and ranches. What they may not realize is dairy cows are a big part of Texas agriculture, too. Texas ranks fifth nationally in dairy production and in its number of dairy cows, and the industry is growing rapidly, despite challenges such as freezes and COVID-19 in recent years.

Good for Bones and the Economy

According to a June 2021 report by the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA), the Texas dairy industry — including production and wholesale and retail sales — accounts for a total economic impact of $50.3 billion in Texas, or nearly 3 percent of the gross state product. The IDFA estimates the Texas dairy industry generates $12.7 billion in total wages for 253,000 direct and indirect jobs.

The IDFA report tallies Texas exports at $486 million worth of dairy products each year, and it is among the top five U.S. states in dairy exports. Also the top state in total exports, Texas sends about 37 percent of its agricultural exports to Mexico, our largest international trading partner for such products.

Fifty years ago, Texas dairies had an estimated 355,000 dairy cows (Exhibit 1). By 2020, that number had increased to 595,000, a gain of 67.6 percent, with only four states showing more (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 1: TEXAS DAIRY COWS BY DECADE, 1970 TO 2020

| Year | Number of Dairy Cows in Texas |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 355,000 |

| 1980 | 317,000 |

| 1990 | 386,000 |

| 2000 | 348,000 |

| 2010 | 413,000 |

| 2020 | 595,000 |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service

Exhibit 2: DAIRY COWS: TOP FIVE STATES, 2020

| State | Number of Dairy Cows | U.S. Rank |

|---|---|---|

| California | 1,721,000 | 1 |

| Wisconsin | 1,259,000 | 2 |

| Idaho | 645,000 | 3 |

| New York | 626,000 | 4 |

| Texas | 595,000 | 5 |

| U.S. Total | 9,388,000 |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service

Darren Turley, executive director of the Texas Association of Dairymen, says, “The Texas dairy industry continues to see growth, and we are on track to move up to be the fourth-largest dairy state in the nation, surpassing New York.”

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data estimate cash receipts for milk sales from Texas dairy farms in 2019 were $2.6 billion, the second-highest among the state’s agricultural commodities and 12.5 percent of total receipts (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: TOP FIVE TEXAS AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES BY ESTIMATED CASH RECEIPTS, 2019

| Commodity | Cash Receipts, 2019 | Share of Total | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle and calves | $8.4 billion | 39.6% | 1 |

| Dairy products, milk | $2.6 billion | 12.4% | 2 |

| Cotton lint, upland | $2.6 billion | 12.1% | 3 |

| Broilers | $2.2 billion | 10.2% | 4 |

| Miscellaneous crops | $1.4 billion | 6.7% | 5 |

| Total, all Texas agricultural commodities | $21.2 billion |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service

Fewer, Larger Farms

Despite the state’s growth in dairy production and sales, the actual number of Texas dairy farms declined in recent years. Texas dairy producers today amount to about 12 percent of the total from 45 years ago. Yet production has more than quintupled. In 1975, Texas had 2,890 producers churning out about 3 billion pounds of milk. Today, Texas has just 351 dairies but produced more than 14.8 billion pounds, or more than 1.7 billion gallons, of milk in 2020.

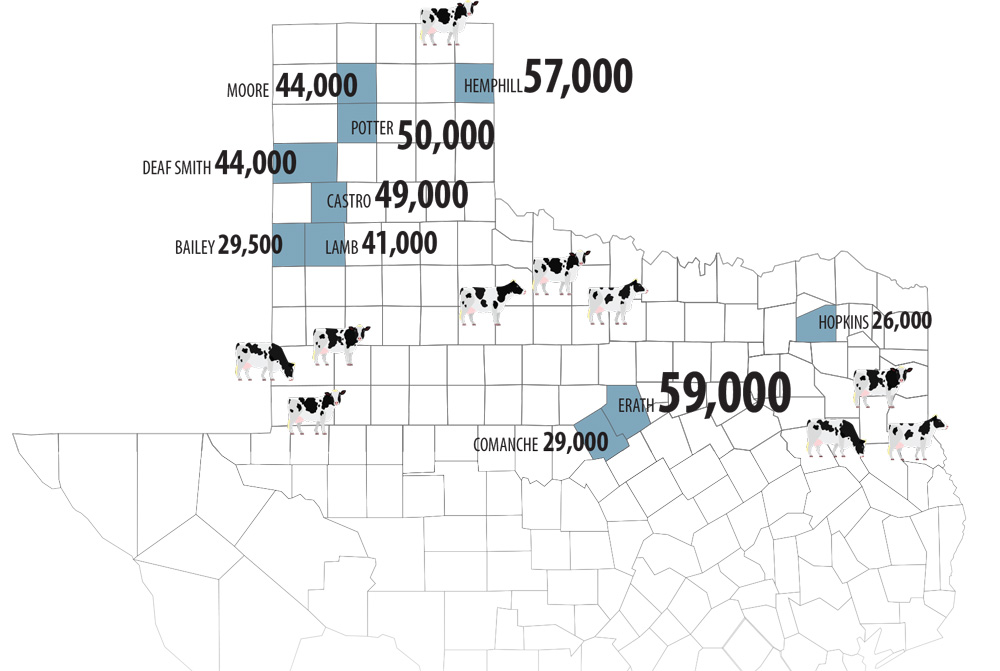

“Texas continues to lose farms, but our farms are both growing in size and producing more milk,” says Turley. Much of this growth is happening in the Texas Panhandle, which now accounts for 80 percent of all Texas dairy production. In the USDA’s report 2020 Texas Agricultural Statistics (PDF), which lists milk-producing cows by county, seven of the 10 counties with the largest dairy cow populations are in the Panhandle area (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: TEXAS DAIRY COWS BY COUNTY, TOP 10 COUNTIES, 2019

| County | Location | Number of Dairy Cows |

|---|---|---|

| Erath | North Central Texas | 59,000 |

| Hemphill | Panhandle | 57,000 |

| Potter | Panhandle | 50,000 |

| Castro | Panhandle | 49,000 |

| Deaf Smith | Panhandle | 44,000 |

| Moore | Panhandle | 44,000 |

| Lamb | Panhandle | 41,000 |

| Bailey | Panhandle | 29,500 |

| Comanche | North Central Texas | 29,000 |

| Hopkins | Northeast Texas | 26,000 |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service

In a 2018 AgriLife Today article, now-retired state dairy specialist Dr. Ellen Jordan, who worked with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension service, attributed much of dairy’s move to the Panhandle to affordable land cost, land availability and weather — specifically low humidity levels, which can improve milk production and fertility. The Panhandle also grows a lot of cotton, and cottonseed is a popular feed for dairy cows.

Blizzards, COVID-19 and Labor Shortages

Texas dairy farmers have weathered some tough times in recent years. On Dec. 26, 2015, a fierce winter storm named Goliath swept into the Texas Plains and Panhandle, dumping record snowfall in large swaths across the state. The blizzard devastated dairy farmers, who not only lost tens of thousands of cows but also had to suspend production.

Photo courtesy of Texas Association of Dairymen

The February 2021 freeze was brutal as well, but this time the state’s dairy farmers were better prepared, Turley says. “Texas dairy producers learned a lot from the Goliath storm event of 2015 to help them prepare for this year’s storm event. Farms now have generators to continue operations and have changed how they manage cows in order to keep them warm in the coldest of times.”

Turley says the February freeze, however, did affect the processing sector of the dairy industry. “Even though farmers continued to milk cows through the storm, processing plants were shut down due to lack of electricity and natural gas, frozen pipes or icy roads. The weeklong shutdown filled available milk haulers, and millions of gallons of milk had to be disposed of because no processing facility could accept it. Not only was this milk that did not make it to market, but it also was a loss in income for dairy farmers.”

As with other industries, dairy farmers have had to contend with the COVID-19 pandemic. A December 2020 study published in the Journal of Integrative Agriculture found that the pandemic greatly affected the U.S. dairy industry. Farm gate milk prices — the prices farmers receive if milk is sold on their farmland — decreased, and the industry experienced “disruption and difficulties of moving milk within the supply chains, worker shortages, increased production costs, and lack of operating capital.” The study further mentioned the shutdown of many U.S. dairy processors due to the closing of schools, restaurants and hotels — all of which are major dairy customers.

Turley says filling industry jobs remains a challenge. “The COVID-19 pandemic initially created some milk oversupply issues when it shut down the food service industry, a significant buyer of dairy products. It also has increased the struggle with a very tight labor market in our rural areas. Our markets are stabilizing, but farm labor is still short.”

Federal COVID-19 relief legislation provided funding for the U.S. industry through the Dairy Margin Coverage Program ($473 million), which provides necessary cash flow assistance to small and mid-sized dairies, and the Dairy Donation Program ($400 million), which pays milk processors for the full value of milk and other dairy products donated to food assistance programs.

High-Tech Dairies

The dairy industry has experienced dramatic changes over the years. Today’s dairy farmers still tend to be family farmers, but with larger, streamlined operations, and the U.S. dairy industry continues to consolidate and modernize. Texas dairy farmers have followed suit by incorporating newer technologies into their operations.

One such technology is an electronic collar that can help identify a cow experiencing early stages of illness. By monitoring rumination (i.e., chewing the cud) and movement — two key indicators of cattle health — the collar sends data over Wi-Fi to a software program that determines if a cow is operating within a healthy range, sort of like a bovine Fitbit.

Robotic milking stalls also are gaining traction in Texas. Two robotic dairies now operate in Snyder and Windthorst in West Texas and the Wichita Falls MSA, respectively. Turley says more are under consideration or construction. “The robotic stalls will change the way dairy farmers manage their cows,” he says. “These milking stalls eliminate the need for labor to milk cows two or three times a day. Dairy farmers have been quick to adopt new technology into their operations, and this is definitely true in Texas.”

Photo courtesy of Texas Association of Dairymen

Some technology also has brought about changes related to sustainability. Natural Prairie Dairy in Dalhart installed a system that processes manure for other uses on the farm, including as an organic fertilizer.

“Texas dairy farmers strive to be good environmental stewards,” Turley says. “They live on or near their farms, and they depend on the land, water and air to make a living and to raise a family.”

In January 2020, the Journal of Animal Science found that the environmental impact of producing a gallon of milk in the U.S. from 2007 to 2017 made noteworthy improvements, including a carbon-footprint reduction of 19.2 percent, which the study attributed primarily to increased efficiency in both feed and milk production.

What's Next for Dairy?

While milk is facing increased competition in the grocery store from plant-based alternatives made from oat, soy, almonds, hemp and other products, Turley predicts milk output in Texas will continue to grow, as will the dairy industry’s movement toward bigger and fewer dairy farms with much larger herds to manage.

And while many of the state’s family dairy farms are operated by multiple generations, the industry is actively encouraging young Texans to consider dairy farming or production as a career. Turley emphasizes that the dairy industry has many career options, and not all of them mean working on a farm.

“The industry is quite broad in its need for all types of employees. There are jobs to meet all interests, from milking cows to veterinary care to marketing and more,” he says. “Our quick-changing industry also needs to fill technology jobs so that robotics being installed on farms can continue to see growth for many years to come.” FN