The (Gradual) 5G Revolution Next-level Internet Coming to Texas

According to the Texas 5G Alliance, the U.S. today has more mobile devices than people. But the next stage of mobile connectivity, a series of innovations collectively dubbed “5G,” promises to be an upgrade bordering on another industrial revolution, fueling advances in areas ranging from autonomous vehicles to remote surgery and factory automation.

In 2019, Mike Wood, an official with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), predicted that 5G and internet-of-things (IoT) applications — sensors and communications technologies embedded in physical objects ranging from refrigerators to pipelines and heavy industrial equipment — would be widespread by 2025. By then, the number of connected IoT devices is projected to be 75 billion worldwide, a 500 percent increase from 2015, according to Jamie Susskind, a vice president of the Consumer Technology Association.

There’s a pragmatic economic necessity driving 5G — the need for more bandwidth. According to Douglas Dawson, owner of telecommunications consulting firm CCG Consulting, mobile data volumes have risen by 25 percent in the last few years, swamping existing 4G networks.

But 5G isn’t widely available yet, and it hasn’t achieved anything like its full potential in the U.S. The Swedish technology company Ericsson estimates global 5G coverage at a billion people, or about 15 percent of the world’s population. Even so, the advent of “smart” technology and the constant business demand for more data are propelling 5G forward.

So What's 5G?

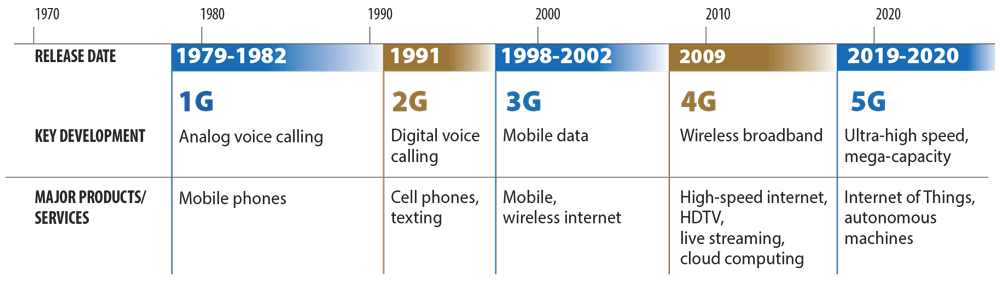

Fifth-generation or 5G technologies represent the next step in the 40-plus-year evolution of mobile communications (Exhibit 1). Each of these five generations introduced new capabilities and services for consumers.

EXHIBIT 1: THE EVOLUTION OF WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS

| Generation | Release Date | Key Development | Major Products/Services |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1G | 1979-82 | analog voice calling | mobile phones |

| 2G | 1991 | digital voice calling | cell phones, texting |

| 3G | 1998-2002 | mobile data | mobile, wireless internet |

| 4G | 2009 | wireless broadband | high-speed internet, HDTV, live streaming, cloud computing |

| 5G | 2019-20 | ultra-high speed, mega-capacity | internet of things, autonomous machines |

Sources: Texas 5G Alliance, Qualcomm, Brainbridge and Digi International

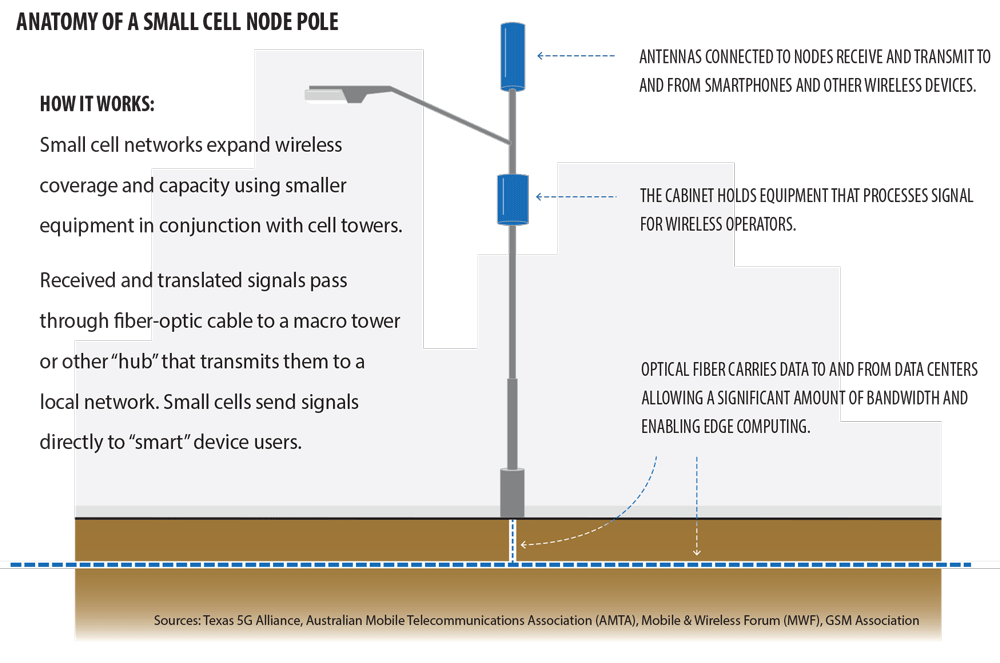

Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of 5G is the use of “small cells,” low-powered antennas that communicate wirelessly via radio waves, usually installed on existing public infrastructure such as street signs or utility poles (Exhibit 2), rather than the large towers used to transmit 4G signals.

EXHIBIT 2: COMPONENTS OF SMALL CELLS

Anatomy of a small cell node pole

How it works:

Small cell networks expand wireless coverage and capacity using smaller equipment in conjuction with cell towers.

Received and translated signals pass through fiber-optic cable to a macro tower or other "hub" that transmits them to a local network. Small cells send signals directly to "smart" device users.

- Antennas connected to nodes receive and transmit to and from smartphones and other wireless devices.

- The cabinet holds equipment that processes signal for wireless operators.

- Optical fiber carrier data to and from data centers, allowing a significant amount of bandwidth and enabling edge computing.

Sources: Texas 5G Alliance, Australian Mobile Telecommunications Association (AMTA), Mobile & Wireless Forum (MWF), GSM Association

Small cells allow wireless carriers to offer increased data capacity, faster connectivity speeds and a better wireless experience. The trade-offs are the small cells’ shorter range and weaker signal penetration, meaning they must be configured more densely and installed in much greater numbers. And they must be connected almost exclusively by underground fiber-optic cable — meaning “wireless internet” isn’t, really. In the current, transitional period, 4G cell towers and 5G small cells will continue to exist and work together.

Another factor differentiating 5G is the portion of the radio spectrum used to transmit it. According to analytics firm Open Signal, every nation with 5G other than the U.S. uses the 3.5GHz mid-band spectrum for it; in the U.S., carriers such as T-Mobile and AT&T often use lower bands that offer lower average speeds. That’s one explanation for average U.S. 5G download speeds that were slower than those of 14 other nations as of mid-2020. The U.S. average speed was 1.8 times faster than 4G, while Spain’s, for instance, was seven times faster.

For wireless companies, the expensive, capital-intensive move to 5G hasn’t yet generated the revenue streams needed to fund new applications and services, according to Grant Spellmeyer, a vice president with U.S. Cellular. Such revenue will be essential to making 5G cost-effective.

The IEC’s Wood says initial 5G applications are likely to be for fixed wireless residential access and enhanced mobile broadband. But Chelsea Collier, founder of the digital communications forum Digi-City, sees a bigger picture emerging.

“The real application is IoT and processing data at the edge,” Collier says. With 5G-enabled “edge computing,” data from embedded sensors can be processed and used on site — a capability that would prove essential for the broader use of autonomous vehicles, for instance.

“When you can analyze and manipulate data where it’s collected, you can deliver insights and value more quickly,” Collier says.

A 5G GLOSSARY

- Bandwidth: the maximum amount of data that can be transmitted over an internet connection in a given amount of time; refers to volume of information, not internet speed.

- Broadband: a catch-all term for high-speed internet access; technically, a wide band of radio frequencies providing minimum speeds of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) download and 3 Mbps upload, according to the FCC.

- Edge computing: a distributed computing framework that processes data at the source, rather than at data centers or on cloud servers.

- Internet of things (IoT): interconnected “smart” devices containing both sensors and data processing functions.

- Internet speed: rate at which digital data are transferred, both for download and upload; measured in Mbps. The current high-speed internet standard is 25/3 Mbps, download/upload.

- Latency: amount of elapsed time (delay) between accessing and receiving internet data or initiating and completing a function online; measured in milliseconds.

- Spectrum: electromagnetic waves dedicated to specific uses, such as TV, radio and cellular service, divided into frequencies or bands, some of which are crucial to 5G.

- Wi-Fi: technology used to connect computers and other electronics to each other, networks and the internet via a wireless signal.

Sources: Ken’s Tech Tips, AT&T, ZDNet, Boston Consulting Group, CNet, FCC, TechTerms, Verizon, Highspeedinternet.com, Digi International

Federal Role

On Dec. 7, 2020, the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC’s) Rural Digital Opportunity Fund allocated $9.2 billion to 180 providers to deploy high-speed broadband in the next decade to 5.2 million homes and businesses nationwide. In Texas, 22 companies will receive nearly $362.7 million (PDF). Texas’ share will be spent in 220 of its 254 counties; 85 Texas counties will receive at least $1 million each, according to recent media reports.

The FCC also recently completed the latest in a years-long series of spectrum band auctions. On Dec. 8, it auctioned frequencies in the coveted C or mid-band, considered the 5G “sweet spot” due to its optimum ranges of coverage, speed and latency. The tally announced Jan. 15 reflects its value to providers: nearly $81 billion, almost double the previous auction record.

Houston is in the vanguard of small cell permitting in Texas, and not just because it’s the state’s largest city; advocates have lauded its proactive approach to 5G. Other cities, particularly smaller ones, are lagging well behind (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Small Cell Permits by Selected Texas Cities*

| CITY | NUMBER OF APPROVED SITES | NUMBER OF PERMITS OUTSTANDING** | NUMBER OF APPLICANTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOUSTON | 5,455 | NA | NA |

| DALLAS | 1,948 | 248 | 6 |

| SAN ANTONIO | 1,760 | 89 | 5 |

| AUSTIN | 717 | 128 | 3 |

| FORT WORTH | 513 | 102 | 3 |

| EL PASO | 166 | 31 | 3 |

| CORPUS CHRISTI | 90 | 71 | 2 |

| BROWNSVILLE | 48 | NA | 7 |

| MIDLAND | 16 | NA | NA |

| LAREDO | 6 | 14 | 1 |

| AMARILLO | 1 | 27 | 2 |

*As of November/December 2020.

**Pending either city staff review, carrier revisions or both.

Sources: Interviews with municipal government officials

Amandus “Mandy” Derr, director of government affairs for communications infrastructure company Crown Castle, credits 2017 state legislation (Senate Bill 1004) with streamlining and harmonizing municipal administrative procedures applicable to 5G. He singled out Houston and Dallas as moving quickly to greet the new technologies.

5G Everywhere?

Due to its reliance on dense networks of small cells, Dawson describes 5G as primarily an urban technology, noting that Texas’ large number of metropolitan areas positions the state to take greater advantage of it. But the state’s expansive rural areas pose a much bigger challenge.

“Implementation [of 5G] doesn’t mean widespread access because it’s not economically feasible everywhere,” says Jennifer Harris, state program director of Connected Nation Texas.

And access doesn’t equal adoption. Harris says that 30 percent of Texans who live in areas where broadband is already accessible don’t subscribe, mainly due to affordability.

Given Texas’ geographic diversity and sheer size, Harris says logistics will play an “outsized” role in getting everyone online. “We need different technological approaches for different parts of the state,” she says.

Derr believes rural residents may be served best by a combination of government funding and private partnerships with local wireless service providers.

This is the kind of issue state broadband offices are designed to address. Texas is one of six states without such an office, but that could change soon (see “Broadband Expansion in Texas” in this issue).

5G in Industry

Alok Shah, an executive with Samsung Electronics America, believes 5G may be even more important to industry than the consumer sector, especially as coverage increases and latency decreases.

“5G is not one thing to everybody,” Shah observed during a recent podcast in Broadband Breakfast Live Online's ongoing series, “A No-Nonsense Guide to 5G.” He recounted how 5G-related technology already is benefiting Samsung’s Austin semiconductor factory. According to Shah, ethernet cables used to connect much of the plant’s equipment have been replaced with mobile high-speed connections. 5G also provided workers with real-time chat capability, allowing them to provide timely input for troubleshooting.

Other current examples of commercial 5G/IoT applications include remote patient monitoring and diagnostic data collection (Rimidi), drone-enabled wildfire fighting and emergency situation management (Austin-based DroneSense) and even hog farm efficiency (SwineTech).

Coming Soon … Or Not?

Despite a sense of inevitability, some industry watchers don’t expect the 5G revolution to be complete anytime soon. In the short term, wireless providers may take advantage of the additional frequencies opened up by the federal government — and call it 5G, whether or not small-cell networks are entirely functional.

“In 2021,” Dawson predicts, “5G will continue to be 4G delivered on the new spectrum.” He notes that the entire array of 4G benefits wasn’t available until 2019, a decade after its introduction, so he doesn’t expect a mature 5G in the near term. Moreover, some tech observers caution that the advent of full-blown 5G isn’t a foregone conclusion. They emphasize the need to develop public-private partnerships, seek stakeholders’ mutual interests and forge broad-based working relationships.

“If we don’t collaborate both within and across sectors, we will miss out on the real opportunities,” Collier says. FN

For more on 5G technology, visit the Texas 5G Alliance. See how the West Texas community of Monahans is laying the groundwork for high-speed internet.