Public Transit in Texas Vital Systems Under Pressure

At its best, public transit can be a useful, convenient alternative to the overwhelming number of single-occupancy vehicles crowding Texas roads. But even before the pandemic, many public transit systems in Texas and across the nation were facing falling ridership and rising costs.

In the past year, the outlook for public transportation went from bad to worse as the COVID-19 crisis brought even deeper plunges in ridership, service and revenue, suggesting to some it had entered a “death spiral.” Yet many Texans, including many of our most essential workers, haven’t stopped relying on public transit during the pandemic.

As Texas’ explosive population growth continues to put pressure on our roads and transportation networks, advocates hope to keep public transit a viable mobility option. Last November’s ballot victories for transit initiatives in Austin and San Antonio could signal the beginning of a post-COVID recovery.

Who's Riding and Why

The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) reports (PDF) that the state’s public transportation riders took more than 274 million trips in fiscal 2019, using a variety of modes including fixed-route city buses, rural “dial-a-ride” systems and sophisticated networks of buses and light rail in dense urban areas.

According to a 2017 ridership survey cited in TxDOT’s Texas Transportation Plan 2050 (PDF), Texans use public transit mostly for work, health care and shopping or other errands. Urban riders are more likely than their rural counterparts to use public transport to get to and from work, at 27 percent versus 21 percent, respectively. Rural riders are more likely than urban users to rely on it for medical care, at 26 percent versus 18 percent.

Census data indicate that, in terms of population share, Blacks and Hispanics are overrepresented among public transit riders, as are those with relatively low incomes. Comparatively large shares of those with jobs in education, health care, recreation and food services — the workers most affected by the pandemic — use public transit to get to work.

Transit Districts

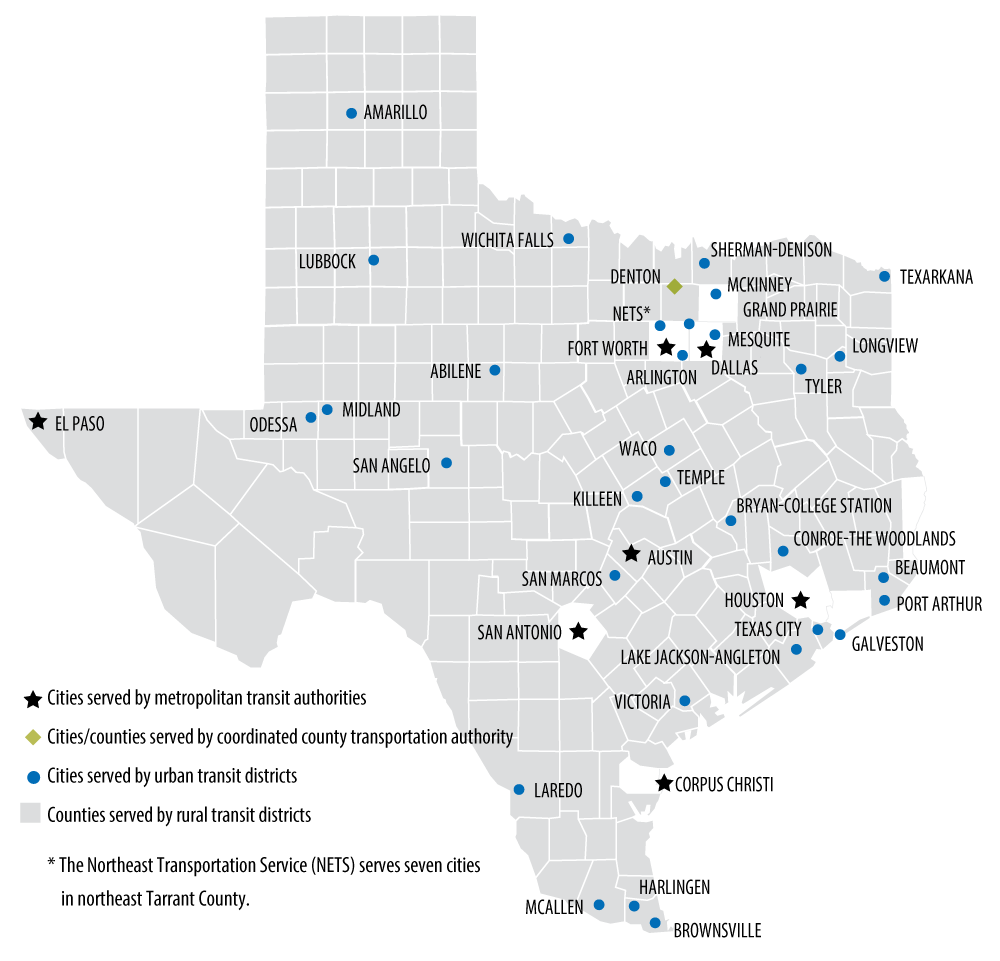

Texas public transit services are provided primarily by three types of entities: rural transit districts, urban transit districts and metropolitan transit authorities, or MTAs (Exhibits 1 and 2). In addition, 58 Texas public entities offer limited service specifically for seniors and those with disabilities.

In fiscal 2019, Texas public transit services for general riders reported total operating expenses of nearly $2.5 billion.

For all types of transit agencies, recent data show a decline in ridership and a persistent rise in operating expenses. Notably, the data in Exhibit 1 don’t include the huge disruptions in ridership and service caused by the pandemic.

Exhibit 1: SELECTED CHARACTERISTICS OF TRANSIT DISTRICT TYPES

| MTAS | URBAN DISTRICTS | RURAL DISTRICTS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NUMBER OF AGENCIES | 8 | 31 (21 SMALL URBAN DISTRICTS, 4 DFW-AREA DISTRICTS,* 6 LARGE URBAN DISTRICTS) |

36 |

| SERVICE-AREA POPULATION | 200,000 AND ABOVE | 50,000 – 199,999 | UNDER 50,000 |

| NUMBER OF PASSENGER VEHICLES | 5,071 | 1,043 | 1,689 |

| RIDERSHIP (UNLINKED TRIPS), FISCAL 2019** |

246,468,960 | 22,663,196 | 4,717,374 |

| RIDERSHIP PER CAPITA | 16.0 | 4.0 | 5.9 |

| RIDERSHIP PERCENT CHANGE, FISCAL 2015-2019 |

-4.8% | -7.0% | -22.1% |

| OPERATING EXPENSE, FISCAL 2019 |

$2,266,682,375 | $127,087,895 | $93,179,748 |

| OPERATING EXPENSE PER TRIP, FISCAL 2019 | $9.01 | $13.64 | $27.57 |

| PERCENT CHANGE IN OPERATING EXPENSES PER TRIP, FISCAL 2015-2019 | 39.5% | 27.5% | 19.0% |

* Four urban districts in the Dallas-Fort Worth area are allowed by state law to operate within the service area of Dallas Area Rapid Transit, the Dallas metropolitan transit authority.

** Note: An “unlinked trip” is a passenger ride on a single vehicle without any transfers.

Source: Texas Department of Transportation

EXHBIT 2: TEXAS TRANSIT DISTRICTS

Source: Texas Department of Transportation

Cities served by metropolitan transit authorities

- El Paso

- San Antonio

- Austin

- Fort Worth

- Dallas

- Corpus Christi

- Houston

Cities/counties served by coordinated county transportation authority

- Denton

Cities served by urban transit districts

- Amarillo

- Lubbock

- Wichita Falls

- Abilene

- Midland

- Odessa

- San Angelo

- Laredo

- McAllen

- Harlingen

- Brownsville

- Victoria

- San Marcos

- Killeen

- Temple

- Waco

- Arlington

- Sherman-Denison

- McKinney Grand Prairie

- NETS*

- Mesquite

- Tyler

- Longview

- Texarkana

- Bryan-College Station

- Conroe-The Woodlands

- Beaumont

- Port Arthur

- Galveston

- Texas City

- Lake Jackson-Angleton

* The Northeast Transportation Service (NETS) served seven cities in northeast Tarrant County

Counties served by rural transit districts

All counties in Texas except the following:

- Tarrant

- Dallas

- Collin

- Bexar

- Newton

- Chambers

- Harris

- Nueces

Rural Transit Districts

Texas’ 36 rural transit districts serve areas with fewer than 50,000 residents. In addition to fixed-route bus service, rural transit often includes demand-response transit, or dial-a-ride, as well.

The largest rural transit districts by ridership are those of El Paso County, Fort Bend County and the city of South Padre Island, each of which delivered more than 400,000 trips in fiscal 2019. From 2015 to 2019, average ridership in rural districts declined by 22.1 percent, far more than in urban areas, although this trend may be exaggerated by a few outliers. Some higher-growth rural districts, in fact, including some in North Texas and the Rio Grande Valley, saw significant increases in their number of riders.

That said, average operating costs per trip in rural districts are the highest by far, due simply to the nature of their service areas, with sparse populations distributed across large geographic areas. TxDOT projects (PDF) a growing revenue gap for rural districts in the coming decades.

Urban Transit Districts

By federal definition, an urban transit district operates a transit system serving a “small urbanized area” of 50,000 to 199,999 people. Twenty-one Texas transit districts fall into this category. Another 10 remain classified as urban districts — and thus remain eligible for state funding — under specific statutory exceptions, even though they operate in areas with 200,000 or more residents.

Texas’ largest urban transit district by ridership is Bryan-College Station, operated by the Brazos Transit District, with 6.7 million passenger trips and $10.8 million in operating expenses in fiscal 2019. The smallest is McKinney in Collin County, with 10,697 trips and $267,000 in expenses that year — but its ridership more than doubled between fiscal 2018 and 2019.

Metropolitan Transit Authorities

Texas’ eight MTAs, each serving areas with 200,000 or more residents, further differ from the other types in their ability to levy local sales taxes to fund their operations. Subtypes in this category include metropolitan rapid transit authorities (in Houston, San Antonio, Austin and Corpus Christi), regional transportation authorities (Dallas and Fort Worth), municipal transit departments (El Paso) and the Denton County Transportation Authority, a joint venture between Denton County and the cities of Denton and Lewisville.

Given the number of people they serve, MTA budgets are much larger than those of the smaller transit agencies. Harris County’s MTA, Houston Metro, delivered more than 90 million passenger trips with $575 million in operating costs in fiscal 2019, followed by Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) at nearly 63 million trips and $987 million in expenses.

This web of agencies and the relationships among them can be complex. Some rural transit districts are becoming urbanized, and some provide services in overlapping urban districts or in partnership with neighboring entities. In the Dallas-Fort Worth area, state law allows four urban districts to operate (and thus to receive state funding) within the DART service area.

Funding Transit

Texas’ transit programs are funded by a mix of federal, state and local sources (Exhibit 3). Fares paid by riders make up only a small portion of their total funding.

All Texas transit agencies are eligible for federal funds, including grants from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and Federal Highway Administration. In fiscal 2019, $472 million in FTA and other federal funds flowed to the three principal types of Texas transit districts. The three major federal stimulus bills passed since the COVID crisis began have provided about $69 billion nationally in additional support for transit.

The Texas Legislature appropriates state funding each biennium to support urban and rural transit districts, but not MTAs, which are authorized to levy local sales taxes that range from 0.25 percent to 1 percent to help fund their operations. Revenue from these taxes exceeded $2 billion in fiscal 2019 and comprised 78 percent of MTAs’ total revenue.

(Laredo’s transit district, El Metro, is an exception as it levies its own local sales tax and is eligible for state funding through a statutory exception. For this analysis, Laredo is counted as an urban district and not an MTA.)

TxDOT provides urban and rural transit districts with direct state funding totaling about $70 million per biennium. For most urban districts, this funding is based on a 50-50 combination of population and four performance indicators that measure local investment, operating efficiency, service effectiveness and per capita use. The rural districts’ funding formula is based upon a 65-35 combination of needs and performance measures.

Transit Challenges

In Texas, discussions of transportation and population growth generally center on the need for adequate roads and highways, but public transit is also an important component for many Texans. Several factors will determine its future.

Population growth: Population densities vary widely across Texas and often dictate a region’s transit needs. The state has added nearly 4 million new residents in the last decade, a 15.3 percent increase since 2010. The vast majority of that growth took place in metropolitan areas; rural regions often saw population declines.

The 2020 Census is expected to underline this trend. Because transit funding formulas are based on decennial census figures, this year’s data release could have dramatic effects on transit funding allocations during the next decade.

Exhibit 3: SOURCE OF REVENUE FOR TRANSIT FUNDING IN TEXAS, FISCAL 2019

Some totals may not add due to rounding.

Sources: Texas A&M Transportation Institute and Texas Department of Transportation

Declining ridership: Despite the nation’s increasing urbanization, transit ridership in general continues to fall. Possible explanations for this trend vary, but many transit providers across the nation have opted to reduce services due to rising costs and competing priorities. In addition, lower gas prices in recent years have made the use of personal vehicles more economical. This, along with rising population in urban areas, increases traffic congestion, which can hurt the reliability of public transit in those areas. And of course, being able to afford a car can significantly improve people’s mobility in rural areas. Furthermore, the need for affordable housing has sent many potential customers farther away from city centers, to more widely dispersed areas with fewer public transit options.

Technology: Meanwhile, technological innovations continue to alter how people move. TxDOT expects ride-hailing services such as Lyft and Uber, automated vehicles and other emerging technologies will reduce public transit ridership by 25 percent by 2050.

Technology also has enabled the enormous rise of telecommuting since the pandemic’s beginning. In October 2020, a Gallup survey found that 33 percent of U.S. respondents were working from home full time, and that figure marked a decline from an earlier peak.

Obviously, this surge was promoted by crisis, and some jobs will always involve in-person work. But in the last year, many organizations found they could continue to function very well with expanded telecommuting, a trend that will almost certainly affect the future of needs-based public transit and its funding.

The Pandemic and After

COVID hit Texas public transit particularly hard. Safety concerns, as well as service limitations due to those concerns, led to big declines in usage. Houston Metro has reported (PDF), for instance, that its total ridership in December 2020 was 53.6 percent lower than in the same month of 2019. Similar trends were seen across the country.

Researchers stress the need to look beyond the status quo to new ideas and modes of mobility. “Multimodalism” — the use of multiple transportation methods working together to serve a region’s customers — can help make transit more appealing for riders.

Michael Walk, a research scientist at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, points to DART as an example. DART employs buses, commuter rail, light rail (powered by overhead electrical lines) and high-occupancy vehicle lanes to move people around the Metroplex.

“DART and its regional partners stand out for their approach,” Walk says. “They don’t limit themselves to traditional transit offerings within individual jurisdictions; instead, they offer regional passes, support innovative services and focus on regional mobility.”

He notes that commuters tend to use the most convenient mode of transportation. “If it’s cheaper and more convenient to take transit, people are more likely to use it,” Walk says.

Despite recent struggles, many Texans still favor public support for transit initiatives. Last November, voters decisively approved ballot measures boosting transit programs in Austin and San Antonio. Advocates credit the success of those initiatives, at least in part, to a focus on successful community engagement.

“Today’s transit ridership levels and trends don’t occur in a vacuum,” Walk says. “They’re largely driven by local, state and federal decisions and investments that make some transportation modes more convenient and affordable than others.

“Can transit service become even more efficient and productive? Sure,” he says. “But transit continues to be the most efficient way to move people in dense areas with limited road capacity.” FN