Amarillo’s Minor League Club Hoping Collegians Can Salvage Season It’s a Whole New Ballgame Thanks to COVID-19

There may be no crying in baseball, but there’s been plenty of angst lately, especially in the minor leagues.

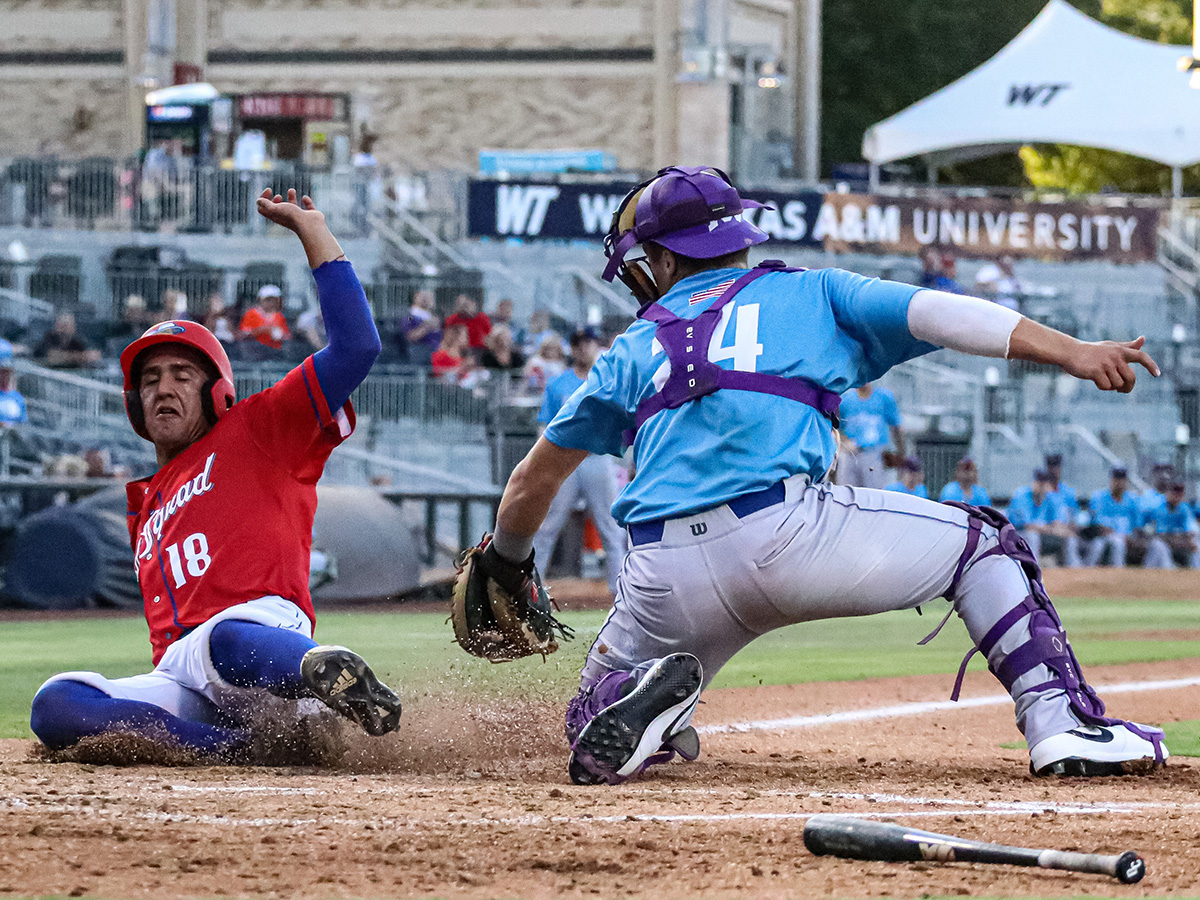

Sod Squad’s Mike Rosario (Miami U.) slides to avoid tag by Sod Dogs’ Kurtis Byrne (TCU) in Amarillo teams’ first meeting July 21. (Ben Jenkins, JYD Productions)

“This is by far the toughest year for the industry in my time in baseball – probably in the history of baseball,” lamented Tony Ensor, president/general manager of the Amarillo Sod Poodles. “And it’s affecting every business out there, not just sports or live attractions.”

Professional sports franchises are especially vulnerable to the pandemic economy, given their event-based nature that means most spectators must sit in relative proximity to each other. Since March, Ensor and his staff have been adjusting their game plan to salvage the season, hoping to somehow offset fixed costs (e.g., stadium lease, payroll) as well as one-time expenditures (e.g., game schedules, fan promotions).

Although Major League Baseball (MLB) has ramped up for an abbreviated season, not so the minors. On June 30, MLB officials announced that their teams would not be supplying players to their affiliates; the decision was not unexpected. With 160 teams across 14 regional leagues and upwards of 3,000 players, Ensor said he began “reading the tea leaves” several weeks ago and realized playing ball this year was unlikely.

For a privately owned small business, the prospect of an 18-month hiatus and the loss of 95 percent of its annual revenue was devastating. The club closed its facilities in late March and laid off almost a third of its staff in April, Ensor said, and some seasonal workers were not rehired. The saving grace has been its ownership by the largest group in Minor League Baseball, plus strong partners, loyal sponsors and enthusiastic fans, 450,000 of whom showed up during the team’s highly successful debut last year.

Like most of its counterparts, the Sod Poodles have been hosting alternative events and opening the stadium bar. But Ensor knew he needed a long-term, sustained effort. That’s when he hit upon the idea of reinventing another lesser-known segment of baseball – the collegiate “wood-bat” leagues.

So called for using the same type bats as the majors (regular college teams use aluminum), these summer leagues feature college players and top pro prospects. Most of the wood-bat leagues weren’t playing either, but Ensor saw an opportunity with the Texas Collegiate League (TCL), which was planning to play.

In about three weeks, officials added six new teams – two in Amarillo – to the four existing squads, organized rosters and hired coaches. In nine cities in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana, there’ll be 30 outings per club from late June through early August.

In Amarillo, team officials have a nine-point plan to ensure fan health and safety at the ballpark including cashless payments, increased sanitation, socially distant seating (approximately 40 percent capacity) and temperature/symptom checks and masking for all staff and concessionaires.

As Ensor explained it, the motivation behind the hybrid league is something of a triple play. For the Sod Poodles and the other franchises, it means income and economic survival. For the fans, it’s the return of live sports and a sense of normalcy. And for the players, it means more exposure and continued career development.

Turnstile Trauma: Crowd-centric COVID-19 Casualties

Here’s a sampling of the pandemic’s adverse impact on other fan-dependent events and venues in Texas (as of July 28, 2020):

- State Fair of Texas (Dallas) – canceled for 2020

- East Texas State Fair (Tyler) – canceled for 2020

- Fiesta (San Antonio) – 2020 festival canceled

- Six Flags Over Texas (Arlington) – opened to the general public June 22 (reservations only)

- Hurricane Harbor Splashtown (Spring) – June 29 opening delayed indefinitely

- Schlitterbahn (New Braunfels) – open with limited capacity (reservations required)

- Six Flags Fiesta Texas (San Antonio) – open daily (reservations required)

- Austin City Limits Music Festival – canceled for 2020

- SeaWorld (San Antonio) – open five days a week, weekends only starting Aug. 15 (reservations required)

- “Texas” outdoor musical (Palo Duro Canyon State Park) – 2020 season canceled

Rally Cap Time

“It’s lifted all our spirits,” Ensor observed.

So have both of Amarillo’s TCL teams – the Sod Squad and the Sod Dogs – each of which opened with two wins. Ensor said attendance has been good, and both teams have winning records. As of July 21, they were in a three-way tie for the division lead (along with the Tulsa Drillers). That week, they played each other at home for the first time.

More importantly, no more layoffs are planned, although getting by on 25-30 percent of revenues won’t be painless. Ensor likens it to stopping the bleeding but not healing the financial wound completely. He feels blessed nonetheless; he expects some minor league teams will struggle to return in 2021.

Topping 2019 was going to be a challenge regardless for the Sod Poodles (the nickname given prairie dogs by early European settlers of the Panhandle). The San Diego Padres AA affiliate was the first team to win the Texas League championship in its inaugural season. It earned league awards for top organization and manager of the year and was tapped to host next year’s all-star game.

Attendance averaged more than 6,200 fans per game in its new ballpark, which sold out 40 times. Team merchandise sales ranked second in the minors, reaching 49 states and six countries.

The 7,300-fan capacity stadium, dubbed Hodgetown after a prominent civic leader and baseball fan, cost $45.3 million to build (team owners chipped in an extra $3 million for assorted amenities). It’s owned by the City of Amarillo, which spent hotel occupancy tax revenue to give the team a home.

Ensor’s confident the minors will resume play next season and the Sod Poodles will re-emerge from their forced hibernation. His West Texas optimism is hard to discount. After all, they don’t do the wave in Hodgetown; they do the “woo!”

Researcher James Tanguma contributed to this article. FN