Open Government Data The Economic Benefits of Transparency

In the information age, much of our economy depends on timely and accurate data. Reliable data derived from trusted sources make for better decision-making in business, communities and our personal lives, whether it’s deciding where to purchase a home, which school districts offer the best opportunities or which job markets are the most promising.

And government represents a near-inexhaustible source of useful and important data. From the census to data on tax collections and government spending, federal, state and local governments gather information on virtually every aspect of our lives and the economy.

Shouldn’t they share it?

The concept of government transparency isn’t new — it dates back at least to 1795, when the U.S. Senate first opened its doors to the public. Since the 1966 federal Freedom of Information Act, transparency has been an increasingly important part of government operations in the U.S. But the truly game-changing moment arrived with the internet, which prompted calls for governments across the nation to provide easy electronic access to their data.

This effort evolved out of the open-source movement, which seeks to make software source code open and free for others to use. Proponents believe that, since government databases are created for public benefit using taxpayer dollars, as much of their information as possible should be provided free to the public via the internet. Thanks to today’s technology, it’s possible to organize, aggregate, analyze and share such data quickly and efficiently.

Open Data for Business and Communities

Businesses and nonprofits across the nation are making increasingly extensive use of government data in their daily operations. A company called Rentlogic, for instance, compiles government data from New York City agencies on health and safety issues to give prospective renters a better look at properties they’re considering. Similarly, Best Buy uses federal demographic data to better analyze and understand its customers.

But communities also have used open government data to improve the lives of their residents, in areas ranging from traffic control to housing programs.

“I’m pleased to see more government data become publicly available,” says Steven Pedigo, director of the LBJ Urban Lab within the University of Texas at Austin’s Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. “Until recently, cities didn’t have access to a lot of data to help guide their decisions, and development policies on the metro and regional levels were more intuitive than data driven. Now, we can access data crucially important to understanding our communities, our state, our neighborhoods and the changes in trends that we’re seeing.”

Communities can use government data to create economic strategies and determine the right types of actions and tactics, although the effort can seem overwhelming at first, Pedigo says.

“Sometimes, data strategy is a bit more of an art than it is a science,” he says. “But if you ask the right kinds of questions, you’ll get answers that will help move you forward. Start with, ‘Here are the things I want to know,’ and then find the right data points to match up with those objectives.

“I firmly believe all economic development, particularly business development, is led by understanding your community’s industry clusters,” Pedigo says. “[Whether] you’re working in rural Texas or in the big city, you have to identify and understand the drivers of your local economy and your community’s special skillsets, and then build your capabilities around those specializations.”

Creating an Open Culture

Professor Sherri Greenberg of the LBJ School of Public Affairs understands how government datasets can help a community improve its local economy. Greenberg’s political experience as a Texas state representative and the city of Austin’s capital finance manager has provided her with a keen appreciation for open government data.

“There is so much government data available to the public,” Greenberg says. “We have the Comptroller’s office, the Legislative Budget Board, the Texas Education Agency and then we have local governments posting their financial statements to the web. And that’s just a small part of what is available to us online.”

Greenberg says nonprofit organizations use open government data by analyzing them and then providing the information in context to the constituents they serve. She notes that some nonprofit groups and private companies, such as Zillow and Yelp, export available government data, “mash it up” with their own proprietary data analytics and visualizations, and then post their findings online as a kind of public service.

“One of my goals has been to increase the availability and the usefulness of open data and to have a culture where we start from the standpoint that — barring personally identifiable information or sensitive information about children or where it is a public safety issue — that data will be open and be useful, usable and provided with context,” Greenberg says. “And I think, yes, the Comptroller’s office has been instrumental in accelerating that culture.”

Open Government at the Comptroller's Office

The Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts has been a national leader in transparency for more than a decade, recognized by entities such as Harvard University with its Innovations in American Government awards.

“Our agency solidly committed to government transparency when we created an online tool, Where the Money Goes, in 2007, enabling the public to search for and download data on state spending by agency, category and vendor,” says Greg Conte, a Data Analysis and Transparency (DAT) Division manager with the Texas Comptroller’s office. “That was quickly followed up with the launch of Where the Money Comes From, our revenue database.”

Those two events marked the beginning of what has become a large collection of datasets on the Comptroller’s website, now maintained by a five-member Transparency Team within DAT dedicated solely to transparency initiatives, both legislatively mandated and agency initiated (Exhibit 1).

EXHIBIT 1: TEXAS COMPTROLLER’S MOST-VIEWED AGENCY TRANSPARENCY WEBPAGES IN 2018

| Web Page | Function | Total Pageviews in 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Webfile Tracker | Tracks taxes filed with the Comptroller's office through its Webfile online payment system | 48,398 |

| State Spending | Where the Money Goes webpage provides data visualizations on spending | 29,858 |

| Databases | Database tools covering a variety of subjects | 22,192 |

| Datasets | Datasets from a variety of sources | 20,490 |

| Tax Allocations | Monthly sales tax allocation summary reports | 11,979 |

| Eminent Domain | Eminent domain reporting, with links to the Eminent Domain Database | 10,224 |

Source: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

The team’s mission centers on providing useful data for policymakers and the public on subjects ranging from local government debt and public pension plans to information about local bond elections, all provided on the agency’s transparency site.

The Transparency Team’s duties include collecting and maintaining transparency data from public entities; creating reports and designing search tools; and serving as points of contact for questions about the data from the public, local governments and state legislators. Under current agency policy, all email inquiries to the team must be acknowledged or answered within eight business hours. The Transparency Team also maintains a toll-free hotline (844-519-5676) to answer general questions or address concerns regarding any of its programs.

Managing open government data for the agency does feel like a balancing act at times, Conte admits.

“First, we must ensure that we don’t expose the agency or taxpayers to any risk from a cybersecurity aspect,” he says. “Second, open government data is not about putting everything online, but being smart about what kind of information we’re putting online. Are we putting out numbers just for the sake of putting out numbers? We want our data to be relevant to the public’s needs.”

Transparency Stars Program

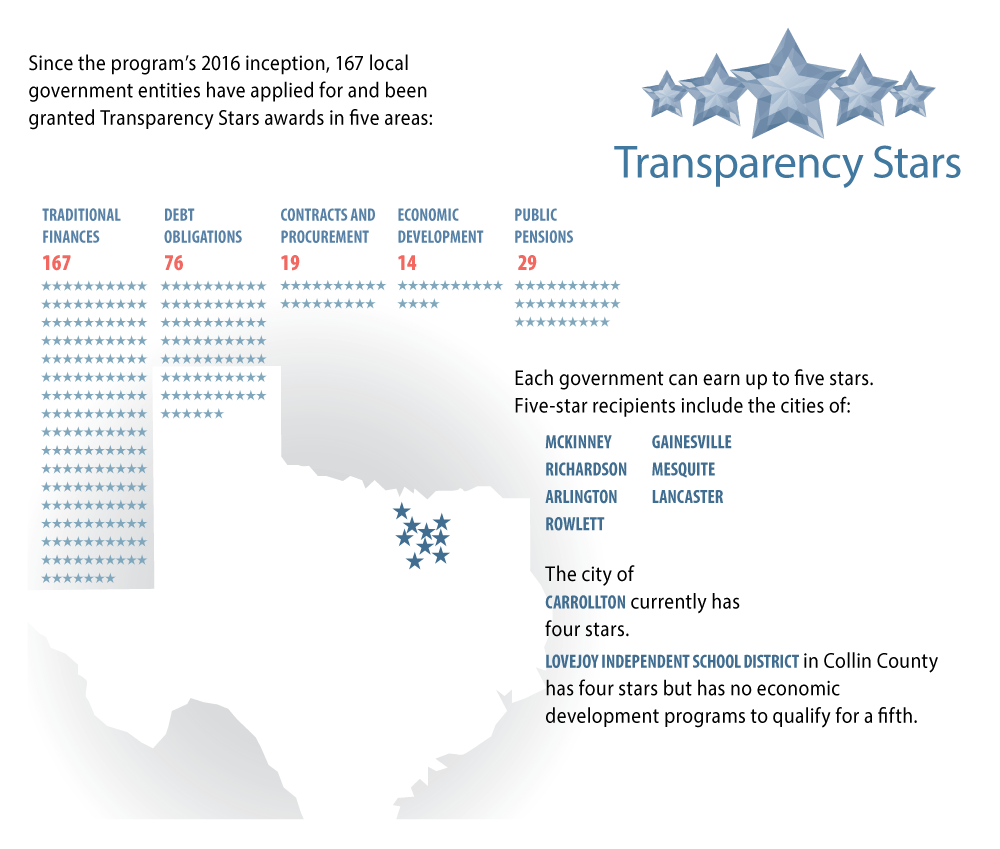

The Transparency Team also administers the agency’s Transparency Stars program, which recognizes local government entities for exceptional transparency efforts in publishing not only traditional financial information such as budgets, but also data on contracts, purchasing, pensions and debt. Award winners provide downloadable data as well as summaries, visualizations and other tools that make the data easier to understand and use (Exhibit 2).

“We created the Transparency Stars program to perpetuate a culture of transparency within Texas government by recognizing and rewarding exceptional transparency efforts,” Conte says.

EXHIBIT 2: TRANSPARENCY STARS

Since the program's 2016 inception, 167 local government entities have applied for and been granted Transparency Stars award in five areas:

- Traditional Finances: 167

- Debt Obligations: 76

- Contracts and Procurement: 19

- Economic Development: 14

- Public Pensions: 29

Each government can earn up to five stars. Five-star recipients include the cities of:

- McKinney

- Richardson

- Arlington

- Rowlett

- Gainesville

- Mesquite

- Lancaster

The city of Carrollton currently has four stars.

Lovejoy Independent School District in Colin County has four stars but has no economic development programs to qualify for a fifth.

Open Government and Public Information Requests

Internet-driven open government initiatives have greatly improved access to public data. Formerly, the only way to access much state government data in Texas was to file a public information request (PIR) under the Texas Public Information Act (originally called the Texas Open Records Act), which dates back to 1973. Texas Government Code Chapter 552, which codifies the act, establishes that “government is the servant and not the master of the people,” and goes on to state “[t]he people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not.”

The process of filing a PIR can be a tedious affair and, depending on the request, can take days or even weeks to process.

“Since we’re the state finance agency, people made a lot of PIRs before our transparency efforts,” Conte says. “If I were a researcher, I would think, ‘Why isn’t this information freely available?’ We try to be empathetic to those needs by providing the public with useful information online, without any barriers. This simplifies the process and helps our Open Records Team fulfill more complicated, time-consuming requests.”

Transparency Shop Won't Stop

Meanwhile, Conte’s Transparency Team continues to make improvements to the Comptroller’s Transparency website, whether it’s consolidating reports to improve the user’s experience or ensuring that documents comply with state and federal laws requiring equal access to electronic information (including websites and other digital communications) for persons with disabilities.

“Comptroller [Glenn] Hegar wants a one-stop shop,” Conte says. “That’s what we’re focusing on — gearing our reporting systems to really communicate with each other and make our data easy to find, easy to download and easy to analyze.

“It would be great for the Comptroller’s office to be the beacon on the hill and have other agencies ask us how we did it,” he says. “We’re a large agency, and while we already have a good reputation when it comes to the transparency arena, we’re not stopping. We’re just going to keep working to make our data as open, transparent and accessible as possible.” FN