“Future-Proofing” Texas Against Natural DisasterThe State Plans for the Next Storm

After Hurricane Harvey slammed the Texas Gulf Coast in 2017, state leaders recognized the need to improve our ability to prepare for the inevitable storms to follow.

Gov. Greg Abbott assembled a special group, the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas, both to assist with recovery operations and to recommend improvements in communication, coordination and infrastructure to lessen the impact of future hurricane events.

The commission, led by Texas A&M University System Chancellor John Sharp, issued its Eye of the Storm (PDF) report in November 2018. In evaluating ways to improve Texas’ resilience to storms, the report reached into Texas history for a role model: Galveston residents’ response to the 1900 hurricane that claimed thousands of lives.

In the words of the report:

While many storms have lashed the island since then, many fewer people have suffered and much less damage has been done. The reason for this can be attributed to two lessons learned in that tragic year. First, the people of Galveston were better prepared and took approaching storms more seriously. And second, they elevated an entire island and built a seawall. We should recognize that those lessons remain vital and relevant to Texas today.

More than a century later, state and local leaders are taking steps to “future-proof” Texas — to improve its ability to prepare, withstand and recover — with lessons learned from Harvey, the second-costliest hurricane in U.S. history.

Harvey’s Toll

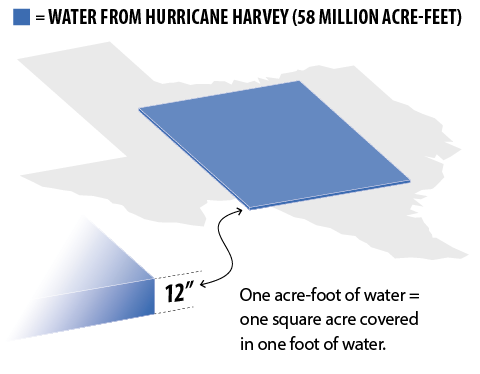

In six days, Harvey caused historic flooding, dumping about 58 million acre-feet of water on the Texas coast. Some areas received as much as 60 inches of rain. Storm surges pushed two to 12 feet of water onshore. Wind gusts of up to 145 mph destroyed residences and businesses alike. At least 68 people died as a direct result of the hurricane, mostly by drowning, while about 35 died from indirect effects such as motor-vehicle accidents. About 42,000 people were forced into shelters.

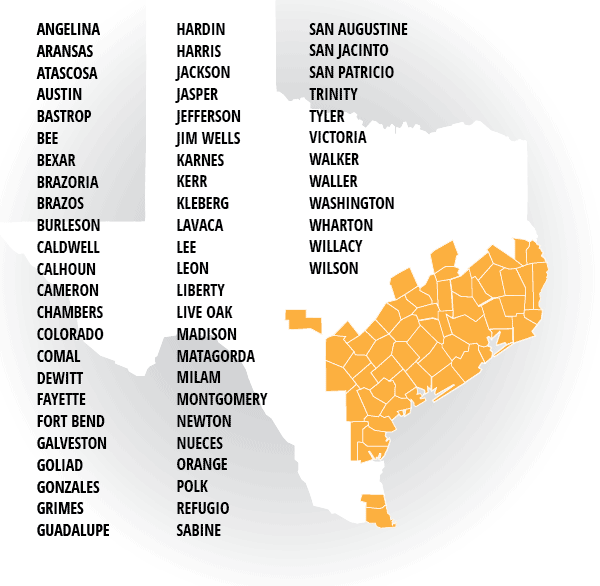

In all, Gov. Abbott ultimately issued disaster declarations for 60 Texas counties, mostly on the coast but some located well away from the main areas of devastation (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1 Texas Counties Included in Texas Harvey-Related Disaster Declarations

- Angelina

- Aransas

- Atascosa

- Austin

- Bastrop

- Bee

- Bexar

- Brazoria

- Brazos

- Burleson

- Caldwell

- Calhoun

- Cameron

- Chambers

- Colorado

- Comal

- DeWitt

- Fayette

- Fort Bend

- Galveston

- Goliad

- Gonzales

- Grimes

- Guadalupe

- Hardin

- Harris

- Jackson

- Jasper

- Jefferson

- Jim Wells

- Karnes

- Kerr

- Kleberg

- Lavaca

- Lee

- Leon

- Liberty

- Live Oak

- Madison

- Matagorda

- Milam

- Montgomery

- Newton

- Nueces

- Orange

- Polk

- Refugio

- Sabine

- San Augustine

- San Jacinto

- San Patricio

- Trinity

- Tyler

- Victoria

- Walker

- Waller

- Washington

- Wharton

- Willacy

- Wilson

Source: Office of the Governor

The Comptroller’s office estimated that the storm’s net economic impact decreased the Texas gross state product (GSP) by $3.8 billion in the first year after landfall, although activity associated with reconstruction and recovery caused the economy to regain ground quickly, producing an expected $800 million gain to GSP after three years.

EXHIBIT 2 Aid Provided to Harvey Survivors as of Jan. 7, 2019

| Type of Aid | Amount |

|---|---|

| National Flood Insurance Program, advance payments and claims paid (estimate) | $8.80 billion |

| Small Business Administration disaster loans approved | $3.42 billion |

| FEMA Individual Assistance payments | $1.64 billion |

| Texas Windstorm Insurance Association | $1.61 billion |

| Total | $15.47 billion |

Sources: U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Small Business Administration and Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service

The cleanup tasks were enormous. In late February 2018, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) estimated that nearly 13 million cubic yards of debris had been cleared from affected areas; the city of Rockport alone was forced to cope with 2.5 million cubic yards of debris.

Soon after the storm, aid began flowing to Texans who had suffered losses. As of January 2019, nearly $15.5 billion had been paid to address Harvey claims through the National Flood Insurance Program, the Texas Windstorm Insurance Association, the Small Business Administration and the FEMA Individual Assistance program, which covers housing and other disaster-related expenses (Exhibit 2).

The Next Storm

In readying the state for future storms, leaders must rally support for changes whose value won’t be fully realized until the next disaster. That can be tricky.

“It’s a rainy-day problem,” says Billy Hamilton, deputy chancellor and chief financial officer for the Texas A&M University System, who guided preparation of the commission’s report. “When people are in danger of drowning, everybody understands somebody needs to do something. And then the sun comes out, and the water goes away. People clean up the worst of the muck, and they haul off the debris, and we sort of go back to our sense of complacency.

Billy Hamilton

Deputy Chancellor and

Chief Financial Officer,

Texas A&M University System

“Texas has the best response to emergency situations in the country,” he says. “It is the model. But recovery, planning, mitigation — it’s never been as well organized. And it’s not like we can point to some other place and say, ‘Well, they’re doing a lot better job.’ Everybody’s in the same boat. The biggest challenge this far removed from the storm is to keep people recognizing that an enormous amount still needs to be done.”

Eye of the Storm explores Harvey’s impact while assessing the response and prioritizing steps needed to accomplish the immense task of improving the state’s long-term recovery efforts and its resilience.

The report’s recommendations include:

- ensuring state emergency responders are effectively organized, trained and equipped, and that local officials and emergency managers have better training.

- improving communication and coordination among state and local officials with emergency responsibilities. As an example, the report cited the use of Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service agents, who are stationed throughout the state, as a “force multiplier” to speed communications among emergency professionals in the field and state and local officials. During Harvey, the agents forwarded local requests, comments and concerns to a response center at the Texas A&M University System, where experts worked to get answers. The exchanges were logged, allowing for analysis. The report recommends institutionalizing this arrangement.

- providing more timely assistance to survivors. The report suggests using state employees from various entities to create “recovery task forces” to help in specialized areas such as financial assistance.

- providing better, easily accessible information about storm risks to potential property purchasers as well as existing homeowners.

- using regulations and incentives to guide development away from areas at high risk of flooding.

- creating a catastrophic debris management plan and a guide to help local officials with the task.

- improving the state’s ability to withstand disasters through infrastructure projects. The report pointed out that billions in federal, state and local dollars are being spent in Harvey’s wake, calling it essential that “we don’t simply replace what was destroyed but that we also increase the state’s resilience.”

The commission worked with the Texas Division of Emergency Management (TDEM) to compile a list of more than 4,000 potential hazard-mitigation projects in counties affected by Harvey that would cost a total of $108 billion. The projects range from repairing public buildings at an expense of a few million dollars to an ambitious “coastal spine,” a barrier to protect against storm surges on Galveston Bay and the Houston Ship Channel that could cost as much as $11.4 billion.

Abbott presented a priority list of $61 billion worth of these projects to Congress and the Trump administration. Eye of the Storm noted that the federal government hadn’t come close to providing so much money to Texas, and that the Texas Legislature couldn’t be expected to allocate a giant lump sum in one legislative session or even in several sessions. But the report says it’s important to rank projects so the state can plan to strategically allocate funds as they become available.

Among steps taken thus far, Harris County voters have approved a $2.5 billion flood bond package for infrastructure projects, and Gov. Abbott signed an executive order (PDF) updating and expanding the State Emergency Management Council, which is charged with advising and assisting the governor with disaster mitigation, emergency preparedness, disaster response and recovery, to include 39 public and private entities.

In addition, TDEM was tied to the Texas A&M University System when the division’s chief, Nim Kidd, became a system vice chancellor while still heading the emergency division. The move is meant to smooth the process and enhance coordination, Hamilton says, since other emergency response entities are under the auspices of the Texas A&M University System, including the Texas Task Force 1 and Texas Task Force 2 search-and-rescue teams.

2019 Legislation

In the current legislative session, the Texas House and Senate have approved a supplemental appropriations bill, Senate Bill 500, which includes about $3 billion for Harvey-related recovery projects and beefed-up disaster response. A legislative conference committee has been appointed to negotiate differences between the chambers’ versions of the legislation.

Several hurricane-related measures were among the first to get moving in the session. In March, the Texas Senate approved SBs 6, 7 and 8 to, respectively, improve local response to disasters; create a Texas Infrastructure Resiliency Fund to boost funding for flood-mitigation projects and allow the state to draw federal matching funds for rebuilding; and create a flood mitigation plan to guide both state and local flood control efforts, including a “statewide, ranked list of ongoing and proposed flood control and mitigation projects and strategies.”

In April, the House approved a proposed constitutional amendment and a bill to implement it — House Joint Resolution 4 (HJR 4) and House Bill 13 — that would create a Flood Infrastructure Fund. The House also approved HBs 5 and 6 to create a debris management plan and a disaster recovery task force, respectively. At this writing, SB 500 is in conference committee. SBs 6, 7 and 8 have passed the Senate; SB 6 has been referred to a House committee, while SBs 7 and 8 have been approved by a House committee and are awaiting debate by the full House. HJR 4 and HB 13 have passed the House and have been referred to a Senate committee.

These efforts recognize that Harvey won’t be the last disaster to test Texas.

“We are the national champions of emergencies, unfortunately,” Hamilton says. “We had the tax-day floods in Houston [in 2016]. We had hurricanes Ike and Carla and Alicia … we have had more federally declared disasters than any other state since records have been kept. They’ve all taught the same lesson, which is we need to do more to prepare, because one of these days, one of these hurricanes is going to come roaring up the ship channel.”

In Eye of the Storm, officials sought to tell the story of the hurricane and its aftermath in a way that showed “yeah, this was a horrible, possibly once-in-a-lifetime thing, but all of the ingredients are there for another hurricane in three years or five years,” Hamilton says.

Pointing again to Galveston’s example, Hamilton says, “They had the good sense to elevate the island … they didn’t sit around and wait for six [thousand] or 12,000 more people to die. They did something. That doesn’t mean they haven’t been hit by hurricanes, but it means a lot less loss of life and damage to property.

“You have to get the experts together; prioritize the needs, because there will never be enough money; and then you have to invest in the things that will best protect people and best protect the infrastructure and the property,” he says, “so that the storms will come, but their impact and the loss of life and all of that won’t be as severe.” FN

Visit the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas.

Looking Back: Hurricane Harvey and the Texas Economy

In February 2018, we examined the effect of Hurricane Harvey on the Texas economy, using a dynamic input-output model to measure the storm’s net economic impacts. View the report.