Emergency Management in Texas How the State Prepares for the Worst

Some of Texas’ greatest strengths spring from its sheer size and geographic diversity. But while these assets contribute to our thriving economy and create many opportunities, they sometimes increase our chances for natural disasters and other emergencies.

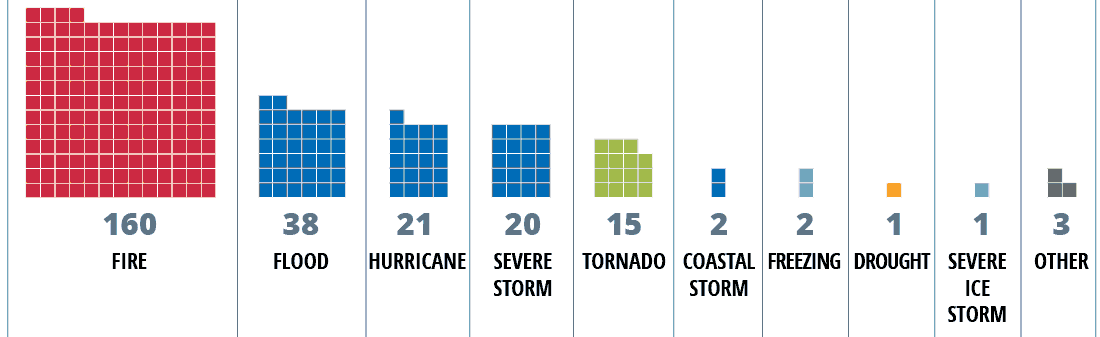

Texas ranks high among U.S. states in its number and variety of natural disasters, ranging from flooding to drought and from wildfires to ice storms. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Texans have experienced 263 federally declared disasters since 1953 (Exhibit 1).

Local governments, particularly those in sparsely populated rural counties, sometimes require assistance with emergency situations due to a lack of the equipment and staffing needed to launch an effective response. The Texas Division of Emergency Management (TDEM), a division of the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS), is charged with coordinating state and local responses to natural disasters and other emergencies in Texas. It’s not an easy job.

“With more than 1,300 jurisdictions, 254 counties, an international border and a long coastline, Texas is constantly faced with unique problems you don’t find anywhere else,” says Kevin Lemon, a TDEM technical operations specialist. “Therefore, we have to have unique solutions.”

Exhibit 1

Federal Disaster Declarations in Texas, 1953-2018

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency

Emergency Management

Emergency management is the practice of formulating procedures with which communities and states can minimize the risk of hazards and disasters and cope with them more effectively.

Local governments, naturally, become the first lines of defense during a disaster. Mayors, county commissioners, municipal police and sheriffs’ departments must alert citizens of imminent threats and take any actions within their means to ensure public order and safety.

For disasters exceeding their abilities and resources, however, a state may step in to provide logistical and financial assistance. In cases in which local and state resources prove inadequate, the state may request assistance from other states through the Emergency Management Assistance Compact, or from the federal government.

In Texas, responsibility for emergency management lay solely with local jurisdictions until the Legislature enacted the Texas Civil Protection Act of 1951, the first law creating a state emergency management organization and statewide emergency management plan. The legislation established a Disaster Relief Council chaired by the governor and comprising various agency heads, each responsible for particular emergency management functions.

The 1951 act was replaced with the Texas Disaster Act of 1975, which further increased the state-local coordination of emergency responsibilities. By 2009, after several phases of reorganization, the Disaster Relief Council had become the Texas Division of Emergency Management within DPS.

According to DPS, “TDEM is charged with carrying out a comprehensive all-hazard emergency management program for the state and for assisting cities, counties and state agencies in planning and implementing their emergency management programs.” Specifically, the Texas Government Code requires TDEM to prepare and keep current a comprehensive state emergency management plan — the basic planning document for emergency management at the state level — and assist in the development and revision of local emergency management plans.

Another part of its mission concerns funding for emergency services; TDEM currently administers more than 50 grant programs for local governments.

Emergency Management Assistance Compact

The Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) is a mutual aid system, first authorized by Congress in 1996, which allows states to request personnel, equipment and supplies from other states to assist with response and recovery efforts. Resources deployed through EMAC, in turn, can draw down federal reimbursement dollars. Within a week after Hurricane Harvey struck Texas, 21 states had sent emergency teams and equipment coordinated through EMAC; ultimately, 36 states assisted.

Texas Emergency Management Council

The Texas Emergency Management Council (EMC) includes 39 state agencies and nonprofit emergency assistance organizations (Exhibit 2). State law established the council to advise and assist the governor in all matters related to disaster mitigation, emergency preparedness, disaster response and recovery.

The State Emergency Management Plan (PDF) assigns 22 emergency support functions to the EMC member organizations, which identify, mobilize and deploy resources to respond to emergencies and disasters (Exhibit 3). The type and extent of a hazard or disaster determines which EMC agencies will respond.

Exhibit 2

Organizations Represented on the Texas Emergency Management Council

- American Red Cross

- Texas Department of Information Resources

- Texas General Land Office

- Texas State Auditor's Office

- Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

- Texas Animal Health Commission

- Texas Office of the Attorney General

- Texas Commission on Environmental Quality

- Texas Commission on Fire Protection

- Texas Department of Agriculture

- Texas Department of Criminal Justice

- Texas Department of Family Protective Services

- Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs

- Texas Department of Insurance

- Texas Department of Public Safety

- Texas Department of State Health Services

- Texas Department of Transportation

- Texas Division of Emergency Management

- Texas Education Agency

- Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service

- Texas A&M Forest Service

- Texas Health and Human Services Commission

- Texas Military Department

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

- Public Utility Commission of Texas

- Railroad Commission of Texas

- Texas Workforce Commission

- The Salvation Army

- Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service

- Texas A&M University System

- Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation

- Texas Department of Motor Vehicles

- Texas Facilities Commission

- Texas State University System

- Texas Tech University System

- Texas Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster

- University of Houston System

- University of North Texas System

- University of Texas System

Source: Texas Division of Emergency Management

Exhibit 3

| Function | Primary State Agency |

|---|---|

| Warning | Texas Division of Emergency Management |

| Communications | Communications Coordination Group |

| Mass Care | Texas Division of Emergency Management |

| Radiological Emergency Management | Department of State Health Services |

| Evacuation | Department of Public Safety |

| Firefighting | Texas A&M Forest Service |

| Law Enforcement | Department of Public Safety |

| Public Health and Medical Services | Department of State Health Services |

| Public Information | Department of Public Safety |

| Recovery | Texas Division of Emergency Management |

| Public Works and Engineering | Texas Department of Transportation |

| Energy | Public Utility Commission of Texas |

| Resource Support | Texas Division of Emergency Management |

| Direction and Control | Texas Division of Emergency Management and Department of Public Safety |

| Animals, Agriculture and Food & Feed Safety | Texas Animal Health Commission; Texas Department of Agriculture; Department of State Health Services |

| Hazard Mitigation | Texas Division of Emergency Management |

| Hazardous Materials and Oil Spill Response | Texas Commission on Environmental Quality |

| Search and Rescue | Texas Engineering Extension Service |

| Transportation | Department of Public Safety |

| Terrorism Incident Response | Department of Public Safety |

| Food and Water | Health and Human Services Commission |

| Military Support | Texas Military Department |

Source: State of Texas Emergency Management Plan (PDF)

Disaster Districts

Initial state emergency assistance for local governments is provided through one of 24 Texas disaster districts, which manage state operations within their designated areas. Each district is led by a disaster district committee (DDC) and a committee chair. DDCs include local representatives of state agencies, boards, commissions and volunteer groups represented on the EMC. Each DDC provides guidance and administrative support for disaster response.

The chair of each DDC is the district’s commanding Highway Patrol officer. The chair also serves as liaison between the State Operations Center (SOC; see below) and local officials during disasters. In addition, a coordinator assigned to each district is responsible for conducting emergency preparedness activities and coordinating emergency operations within the district.

State Operations Center

In 1964, the SOC was established at DPS headquarters in Austin to serve as the state’s disaster monitoring center. Its primary responsibilities include:

- continuously monitoring threats through communications with local entities, news outlets and social media;

- providing notifications and information on emergency incidents to government officials;

- coordinating assistance requests from local governments through the DPS Disaster Districts; and

- allocating and coordinating state personnel and resources to local governments that can no longer respond adequately to an emergency incident.

The SOC maintains four levels of emergency response (Exhibit 4), categories used to notify and gradually increase the readiness of state and local emergency responders based on the degree and progression of specific incidents. The SOC operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, regardless of its emergency response level.

Exhibit 4

| Emergency Response Level | Description | Examples | Typical Notification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level IV - Normal Conditions | No significant hazard or disaster is present. | Ongoing weather and threat monitoring | TDEM staff; local entities (e.g., fire departments, law enforcement, public works) |

| Level III - Increased Readiness | A significant hazard or disaster has not yet occurred, but a heightened level of readiness is warranted due to increased vulnerability to a particular incident. | Tropical weather system developing near Texas; widespread flash flooding; increased fire conditions | TDEM staff; local entities; DPS Disaster Districts; EMC representatives |

| Level II - Escalated Response Conditions | The incident scope has expanded beyond that which can be handled by local responders; normal state and local government operations may be impaired. | Major tornado impact; major fire conditions; hurricane warning | TDEM staff; local entities; DPS Disaster Districts; local elected officials; EMC representatives |

| Level I - Emergency Conditions | The scope of the incident has expanded beyond the response capabilities of local agencies. | Major hurricane impact; large-scale evacuation; hazardous materials spill | Local entities; DPS Disaster Districts; local elected officials; EMC representatives |

Source: Texas Department of Public Safety

During normal conditions (Level IV), the SOC is staffed by a daily operations group that continually monitors various news media and information sources and informs TDEM of any incidents that could raise the emergency response level. When the SOC’s daily operations group alone can no longer manage the needs of local governments or state agencies during an incident — typically at Level II — more staff members are summoned, including those from the EMC.

“During a disaster, the SOC uses a wide range of resources from academia, private-sector companies and local entities,” Lemon says.

Cutting Red Tape: The Comptroller’s Role In Emergency Response

The Comptroller’s Statewide Procurement Division (SPD) is the state’s central authority on purchasing policy and professional purchasing training.

But SPD also plays a major role in procurement under emergency conditions. Should the Texas governor declare a state of disaster by executive order or proclamation, he or she may suspend the enforcement of certain laws and administrative rules regarding contracting and purchasing that could impede any agency’s emergency response in a disaster. This allows SPD to work with agencies and vendors to get emergency supplies and equipment to first responders and Texans in need as quickly and efficiently as possible.

During Hurricane Harvey and its immediate recovery, members of SPD’s Procurement Policy and Outreach team were stationed and available at the State Operations Center around the clock to facilitate any purchase requested by emergency responders and local governments. Additional SPD and Comptroller staff supported this team to approve purchasing requests immediately and as needed.

In a single weekend, for instance, SPD staff initiated purchases worth more than $15 million for mobile fueling stations, evacuation buses, bottled water and ice, showering stations, portable toilets, heavy equipment for recovery efforts and other items for emergency shelters and rescue efforts.

SPD has worked with the Texas Division of Emergency Management to support recovery efforts during hurricanes in 2005, 2007, 2008 and 2017; the Bastrop fires in 2011; the West fertilizer plant explosion in 2013; and many other disasters. To show thanks for the division’s efforts during Hurricane Harvey, TDEM provided each SPD staffer who assisted with a certificate of appreciation and a commemorative Hurricane Harvey coin.

In the Bunker

As Hurricane Harvey bore down on the Texas coast in August 2017, Gov. Greg Abbott commanded the state’s emergency response efforts from an underground post beneath the DPS building in north Austin. Located three stories below ground level, the State Operations Center has been headquarters for state emergency response for nearly 60 years.

Construction of the SOC began in 1962. A reflection of Cold War tensions, the entire structure is contained within a shock-absorbing concrete room and buried deep underground. Protected by steel blast doors, the structure, nicknamed “The Bunker,” originally was designed to ensure the continuity of state government in the event of a nuclear attack.

Photo courtesy of Texas Division of Emergency Management.

While some vestiges of the SOC’s mid-20th century origins can still be seen (a shower turned storage closet still has a “decontamination” sign over the door, for example), subsequent construction and renovations have turned the center into a modern facility with state-of-the-art technology, safety features and communications capabilities.

During major emergencies, the governor activates the members of the EMC, who assemble at the SOC where they join its daily operations staff and TDEM members to organize a coordinated response. The SOC monitors and manages about 3,000 to 4,000 emergency incidents per year.

It’s no surprise that Texas frequently experiences emergencies of one kind or another, simply because of its size and variable climate. What’s more noteworthy, however, is the state’s ability to respond to a plethora of potentially life-threatening incidents. By integrating the efforts of dozens of organizations, both public and private, and managing the complex logistics from a centralized command post, Texas sets a national example for statewide emergency management. FN