Texas Cybersecurity: Protecting Data SystemsTexans Lose Big to Cybercrime

Cybercrime — the use of computer technology or the internet to gain unauthorized access to information for exploitative or malicious purposes — is a growing threat to private companies, governments and individual consumers alike.

The internet, arguably one of our most important technologies, wasn’t designed to cope with today’s sheer volume of connectivity. Due to the rise of mobile and “smart” devices as well as wireless technologies, huge amounts of confidential information are regularly transmitted across inadequately defended networks with an ever-increasing number of access points available for attack. To compound matters, many information security and data protection measures, such as firewalls and anti-virus software, are becoming ineffective against sophisticated criminal tactics.

Crime on the internet is soaring, and the reasons are simple. The theft of confidential information or intellectual property is relatively easy and can be highly lucrative; furthermore, it’s largely risk-free — most cybercriminals are never caught or prosecuted. And there’s a constantly growing number of targets, as new internet and mobile users log on worldwide each day.

Yet just as a body’s immune system fights back against disease, economic threats breed economic countermeasures — in this case, the young but burgeoning cybersecurity industry, which already employs thousands of Texans.

The Cost of Cybercrime

It only takes one ill-fated click for an individual or organization to fall prey to a devastating cyberattack. The security software company McAfee estimates (PDF) that of the more than 2 billion people online worldwide, two-thirds have had their personal information stolen or compromised. A 2017 global study (PDF) by consulting firm Accenture found an average of 130 security breaches per company each year.

Based on more than 21,000 interviews with representatives of 254 companies in seven nations, Accenture estimates that cybercrime costs each of these organizations an average of $11.7 million annually. This average includes not only the initial costs incurred from damages — which can range from loss of assets to disruption of business continuity — but the money organizations have to spend to recover from damages and protect themselves against the constant deluge of cyberthreats.

Unsurprisingly, banks are the top targets of cybercriminals. The financial services industry has the highest average cybercrime costs, at nearly $18.3 million per organization (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1

Average Annualized cost of cybercrime by industry sector, per organization, August 2017

| Industry Sector | Average Annualized Cost

(in millions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Financial Services | $18.3 |

| Utilities and Energy | $17.2 |

| Aerospace and Defense | $14.5 |

| Technology and Software | $13.2 |

| Health Care | $12.5 |

| Services | $11.1 |

| Industrial/Manufacturing | $10.2 |

| Retail | $9.3 |

| Public Sector | $8.3 |

| Transportation | $7.4 |

| Consumer Products | $7.3 |

| Life Science | $6.5 |

| Education | $5.1 |

| Hospitality | $5.0 |

Source: Accenture and Ponemon Institute LLC

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Internet Crime Complaint Center receives more than 800 complaints of criminal activity per day. In 2017, U.S. victims reported losses totaling $1.42 billion.

Given Texas’ population, it’s unsurprising that the state ranks third nationally in its number of cybercrime victims (Exhibit 2). Texas victims reported about $115.7 million in losses in 2017.

Exhibit 2Top 10 States by number of cybercrime victims and financial losses, 2017

| Rank | State | Victims |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | California | 41,974 |

| 2 | Florida | 21,887 |

| 3 | TEXAS | 21,852 |

| 4 | New York | 17,622 |

| 5 | Pennsylvania | 11,348 |

| 6 | Virginia | 9,436 |

| 7 | Illinois | 9,381 |

| 8 | Ohio | 8,157 |

| 9 | Colorado | 7,909 |

| 10 | New Jersey | 7,757 |

| Rank | State | Losses |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | California | $214,217,307 |

| 2 | TEXAS | $115,680,902 |

| 3 | Florida | $110,620,330 |

| 4 | New York | $88,633,788 |

| 5 | Arizona | $59,366,635 |

| 6 | Washington | $42,991,213 |

| 7 | Illinois | $42,894,106 |

| 8 | New Jersey | $40,441,739 |

| 9 | Colorado | $39,935,041 |

| 10 | Massachusetts | $38,962,867 |

NOTE: Information based on the total number of complaints in which the complainant provided state information.

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation

Cyberattacks are becoming more common and costlier. In response, organizations are investing in information security capabilities and staff on an unprecedented scale. Inevitably, cybersecurity has become one of the largest and fastest-growing technology needs.

Cybersecurity in Texas

Cybersecurity is a relatively new field — so new it hasn’t yet been defined as an industry by the federal government’s North American Industry Classification System, the standard federal agencies use to collect, analyze and publish statistical data related to the business economy.

Even differentiating cybersecurity jobs from other information technology (IT) positions can be difficult. The Department of Homeland Security recently noted inconsistencies in the way employers define and use the term, which can include a wide range of job functions requiring different qualifications and skillsets. Job descriptions and titles for the same job vary from employer to employer. Some researchers and industry practitioners contend that every IT job is involved in cybersecurity to some extent.

The Comptroller’s office has examined employment statistics for information security analysts, defined by the federal Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system as workers who “plan, implement, upgrade, or monitor security measures for the protection of computer networks and information … and respond to computer security breaches and viruses.”

In 2017, 8,165 Texans worked as information security analysts in various sectors of the state economy. The largest numbers were employed in professional, scientific and technical services and finance and insurance, with 3,091 and 1,471 jobs, respectively (Exhibit 3). Emsi, a company that provides labor market statistics, expects robust job growth in this field in multiple sectors.

Exhibit 3

| Industry Sector* | Jobs in Industry, 2017 | Occupation Share by Industry, 2017 | Projected Jobs in Industry, 2027 | Projected Change in Job Count, 2017 to 2027 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | 3,091 | 37.9% | 4,931 | 59.5% |

| Finance and Insurance | 1,471 | 18.0% | 2,010 | 36.6% |

| Government | 676 | 8.3% | 744 | 10.1% |

| Information | 659 | 8.1% | 804 | 22.0% |

| Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services | 528 | 6.5% | 628 | 18.9% |

| Management of Companies and Enterprises | 509 | 6.2% | 822 | 61.5% |

| Manufacturing | 341 | 4.2% | 328 | -3.8% |

| Wholesale Trade | 284 | 3.5% | 317 | 11.6% |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 157 | 1.9% | 210 | 33.8% |

| Mining, Quarrying and Oil and Gas Extraction | 124 | 1.5% | 193 | 55.6% |

*As defined by the federal North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)

Source: Emsi

San Antonio — A National Leader

San Antonio, a nationally recognized hub for cybersecurity, hosts several colleges and universities recognized as National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cyber Defense Education — most notably the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA). UTSA is home to three cybersecurity centers and research institutes and has the nation’s top-ranked cybersecurity education program. Program graduates earn average starting salaries of $60,000 to $80,000 annually.

Superior training and education, combined with close proximity to cybersecurity offices and installations of the National Security Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Air Force, have helped the San Antonio area amass the highest concentration of cybersecurity professionals outside of Washington, D.C.

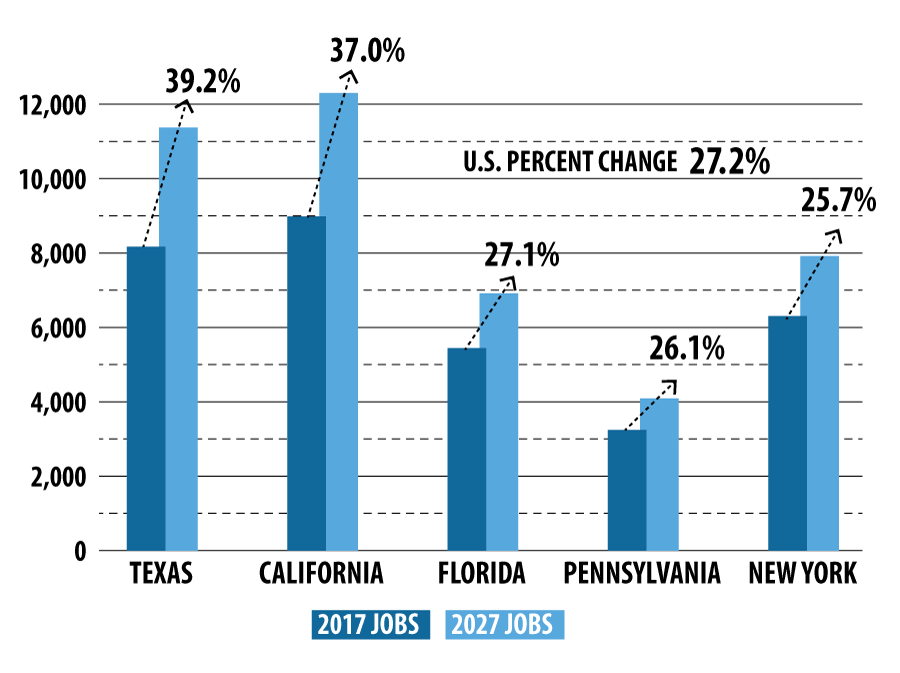

Texas’ job count in this occupation is expected to grow by more than 39 percent from 2017 to 2027 — the largest projected percentage increase among the nation’s five most populous states, and considerably faster growth than in the nation as a whole (Exhibit 4).

Today, the information security analyst occupation has a near-zero unemployment rate.

Exhibit 4

| Region | 2017 Jobs | 2027 Jobs | Numerical Change | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texas | 8,165 | 11,369 | 3,204 | 39.2% |

| California | 8,981 | 12,303 | 3,322 | 37.0% |

| U.S. | 110,905 | 141,058 | 30,153 | 27.2% |

| Florida | 5,443 | 6,916 | 1,473 | 27.1% |

| Pennsylvania | 3,244 | 4,092 | 848 | 26.1% |

| New York | 6,303 | 7,922 | 1,619 | 25.7% |

Source: Emsi

Demand Outpaces Supply

A qualified and well-trained cybersecurity workforce is essential to mitigating and responding to cyberthreats. Demand, however, is outpacing supply, resulting in a global shortage of information security workers.

The research company Cybersecurity Ventures estimates there are more than 1 million vacant cybersecurity positions worldwide. If current trends continue, the number of unfilled cybersecurity jobs will reach 3.5 million by 2021.

Emsi tracked more than 96,000 job postings for information security analysts in Texas from September 2016 to December 2017 alone.

Employers have cited a number of difficulties filling open positions, including a low number of prospects and training shortages. While academic institutions around the nation are developing talented professionals, their programs often are still small and evolving.

According to Dr. Gregory White, professor of computer science and director of the University of Texas at San Antonio’s (UTSA’s) Center for Infrastructure Assurance and Security, the cybersecurity field faces a bottleneck; the nation simply can’t train enough people to fill all open positions and keep up with growing demand. “We could double the number of people in school now and still not fill all open positions,” White says.

Working Around the Labor Shortage

“Organizations need to truly ask themselves if their positions require a [four-year IT] degree,” White says. “I would guess that a number of vacant positions can be filled by people without a degree.”

In fact, many cybersecurity professionals learned the necessary skills through certificate programs and on-the-job training rather than a degree program. “There are students in the San Antonio area that are obtaining two or three certifications in high school and getting job offers after graduation,” White says.

In 2017, nearly a third of information security analysts employed in Texas held less than a four-year degree (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5

| Highest Educational Level | Percent Share |

|---|---|

| Less than high school diploma | 0.7% |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 4.5% |

| Some college, no degree | 16.8% |

| Associate degree | 10.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 42.9% |

| Master’s degree | 22.4% |

| Doctoral or professional degree | 2.3% |

Source: Emsi

According to the 2017 Global Information Security Workforce Study (PDF), many workers enter information security from related fields, most commonly computer science or engineering. Others enter from non-technical careers including the military and defense-related work.

As with other technology fields, there’s a gender gap in cybersecurity. In 2017, only about a fifth of Texas’ information security analysts were women (Exhibit 6). Attracting and retaining a more diverse pool of labor could help improve the labor shortage.

Exhibit 6

| Gender | Employees | Share of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Males | 6,416 | 78.6% |

| Females | 1,749 | 21.4% |

Source: Emsi

Shared Responsibilities

Technical measures alone aren’t enough to counter cyberthreats effectively. Cybersecurity requires all employees to be aware and vigilant.

“In addition to focusing on building the cybersecurity workforce, we also need to work on cybersecurity in the workforce,” says White. Many data breaches have occurred because technology users failed to take the most basic protective measures.

“If we can instill a culture of security in our workforce, it would go a long way to help the minimal number of cybersecurity professionals we have go further,” White says. “It’s not just the professionals’ job to protect the systems. Anyone who touches a keyboard has a responsibility at some level.”

White is also director of the Information Sharing and Analysis Organization Standards Organization (ISAO SO), which works to identify standards, guidelines and best practices for information sharing and analysis related to cybersecurity risks and incidents.

White notes that it was once common for financial institutions not to share cybersecurity information, particularly concerning data breaches, for fear of legal consequences or of losing a competitive advantage. Banks now understand, however, that on this topic, quick, efficient and regular information-sharing is critical. Organizations in other sectors are beginning to do the same thing.

“From a security standpoint, it isn’t one bank versus another bank — it should be both banks versus the attackers,” White says. “Institutions should be teammates in cybersecurity and not competitors.”

Currently, White and the ISAO SO are working to increase cyberthreat information sharing everywhere, in hopes of elevating information security not only in Texas but in the nation as well. FN

See how several Texas colleges and universities are helping create a new generation of cybersecurity professionals in our Line Items feature.