Equity Crowdfunding in Texas A Funding Tool for Small Business

It was intended to help boost a battered economy. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession, the federal Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act was signed into law on April 5, 2012. The JOBS Act eased federal securities regulation on small businesses to allow them to access capital through innovative approaches such as crowdfunding, the use of the internet to tap large numbers of small contributors.

The act’s Title III, Section 302 in particular was envisioned as a positive for small business. Title III provides an exemption from U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registration requirements to allow equity crowdfunding, raising money by selling small ownership shares to many different individual contributors.

The act also opened the door to small business investment opportunities by removing a stipulation that investors must be accredited by the SEC as possessing a net worth of more than $1 million (including spouse) and earnings of more than $200,000 annually ($300,000 with spouse) in the previous two years. The law contains a number of provisions to protect these “nonaccredited” investors, including investment limits, disclosures by the issuing company and a requirement to use regulated intermediaries through an approved online portal.

Congress directed the SEC to release new rules regarding equity crowdfunding and issue disclosure and registration requirements by 2013. The SEC didn’t issue these rules and requirements until May 16, 2016, however.

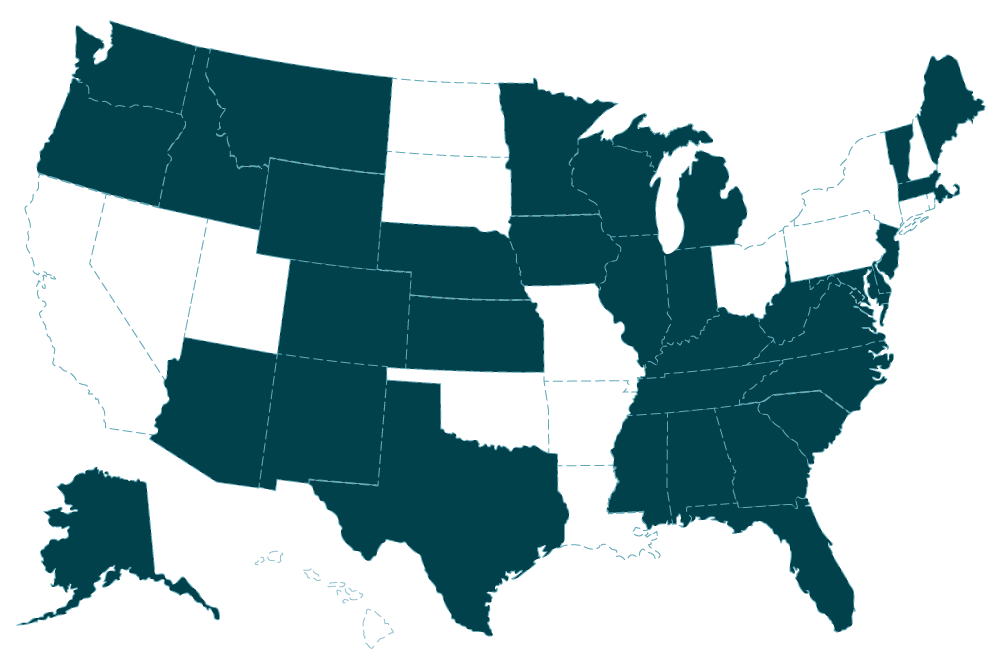

In response to this delay, the Texas State Securities Board (TSSB) implemented the equivalent of Title III in Texas. In 2014, it adopted state equity crowdfunding rules and requirements, allowing small businesses to raise capital within Texas using this approach. Many states did the same; according to the North American Securities Administrators Association, at least 34 states and the District of Columbia have adopted equity crowdfunding rules or statutes (Exhibit 1).

While it was only one part of the JOBS Act, the inclusion of equity crowdfunding caught the attention of many small businesses looking for new funding avenues, says attorney Steve Litke of Weaver, Johnston & Nelson PLLC in Dallas.

“Overall, the act dealt with a number of areas in regulating and updating capital markets and raising capital,” he says. “The intent with the crowdfunding rule was to make it easier for entrepreneurs and small business owners to have another resource to raise capital.”

EXHIBIT 1: STATES WITH INTRASTATE CROWDFUNDING PROVISIONS

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Colorado

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Montana

- Nebraska

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- North Carolina

- Oregon

- South Carolina

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Source: North American Securities Administrators Association

Donations vs. Investments

The concept of crowdfunding isn’t new.

“It’s actually been around quite a while, but donation-based crowdfunding really took off after the introduction of the internet,” Litke says. “Online donation-based crowdfunding platforms such as GoFundMe or Indiegogo make it easy to launch a campaign, but they do not issue securities and cannot provide contributors with a security. They have to find other appealing incentives so people will contribute.”

Incentives offered by crowdfunding campaigns on donation-based platforms might include product discounts, early access to new products, merchandise featuring the company’s logo — or nothing at all.

The Oculus Rift story demonstrates the difference between donation-based crowdfunding and equity crowdfunding. During its early development phase, the Oculus Rift virtual-reality headset was featured on Kickstarter. More than 9,500 donors gave $2.4 million (more than 10 times the campaign’s goal) to take the headset from the drawing board to reality. In return for their contributions, donors who gave $25 received an Oculus Rift T-shirt, while those who offered $275 or more received an unassembled Oculus Rift prototype.

Eighteen months later, Oculus Rift was purchased by Facebook for $3 billion. Had the company been funded through equity crowdfunding instead of donations, those who invested $300 would have seen an estimated $20,000 return on their investments instead of an unassembled headset, according to OnMarket BookBuilds, an investment technology company.

“It’s highly unlikely you’re going to invest in the next Dell using the TSSB or SEC equity crowdfunding portals,” says Litke. “But you never know.”

Uniquely Texan

“The interest in this type of fundraising made it important [that] a structure was in place to allow businesses to tap this method of capital acquisition without inadvertently falling into noncompliance with state and federal securities laws designed to protect investors and legitimate businesses,” says TSSB Commissioner Travis Iles. “Texas created an intrastate crowdfunding structure to bridge the gap while a federal, interstate mechanism was being developed as a result of the passage of the JOBS Act.”

The federal and Texas equity crowdfunding rules are similar in that both require the use of registered, approved crowdfunding portals listed on the SEC or TSSB websites to act as regulated intermediaries between companies and their investors. TSSB regulates Texas crowdfunding portals, and users must comply with its rules of operation. The portals are allowed a certain amount of flexibility in how they raise and distribute investments, and often have focused on different types of investments such as real estate, oil and gas and more.

The Texas equity crowdfunding program possesses some uniquely Texas-centric features:

- companies must use state-certified Texas equity crowdfunding portals, and campaigns are capped at $1 million in any 12-month period.

- any company using a Texas portal must originate in Texas, with a valid Certificate of Formation from the Texas Secretary of State authorizing it to conduct business in the state. The company’s principal place of business also must be located in Texas, and the company must derive 80 percent of its gross revenue from Texas or have 80 percent of its assets located in Texas.

- only Texas residents can invest in a Texas equity crowdfunding campaign, and the amount of securities purchased from any issuing company by a non-accredited investor is capped at $5,000. (There is no dollar limit for SEC-accredited investors.)

- any Texan can participate without proof of income.

To Have and to Hold

While any Texan willing to do so can invest under Texas crowdfunding rules, it’s important that the investment is made with a keen awareness of what to expect, says business attorney R. Shawn McBride of R. Shawn McBride Law Firm, PLLC in Dallas. Investing in a business through equity crowdfunding is very different from buying and selling stocks and bonds in a traditional way, such as on the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ, McBride says.

“You’re going to be a minority investor, which means [you have] a small percentage of the overall ownership of the company,” he says. “You’ll usually have voting rights, but you’ll still be a small fish in a big pond and not have much sway on the company’s decisions. Even if all the company’s crowdfunding investors came together as one voting bloc, it probably wouldn’t be enough to change the course of a proposed action of a company.”

McBride also notes investors using equity crowdfunding should be prepared for their money to become illiquid, or locked up, with the company for years, because it can be difficult to find a buyer for stock in a small private company.

“It’s going to be stuck there for a while,” he says. “If you needed it for an emergency, you’re not going to be able to pull this money out quickly. With small companies, it’s very typical you’ll have trouble finding a buyer — there aren’t as many people who know the company exists because it’s not one of the larger publicly traded companies. And that’s another challenge for privately held companies: you’ve got to figure out what the price of the stock is.

“You’re buying hope,” McBride continues. “The hope is that you’ll find the next big thing. You’re investing in a company that has different characteristics than buying the standard Wall Street stock. A private company has a smaller trading floor, less certainty and more risk.”

Here to Stay?

Since launch, portals hosted on the TSSB website have helped match Texas investors with a wide array of Texas businesses ranging from hair salons and restaurants to oil and gas companies, tech providers and others. In all, equity crowdfunding has raised nearly $2.5 million for small Texas businesses (Exhibit 2).

EXHIBIT 2: TEXAS EQUITY CROWDFUNDING CAMPAIGNS THROUGH APRIL 2019

| Fiscal Year | Number of Offerings | Amount raised through 04/18/2019 |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 9 | $440,672 |

| 2016 | 28 | 1,817,887 |

| 2017 | 7 | 209,200 |

| 2018 | 2 | 25,000 |

Source: Texas State Securities Board

As Exhibit 2 indicates, Texas equity crowdfunding enjoyed some popularity in its first two years, but both the number of Texas companies using equity crowdfunding and the amounts raised have declined precipitously since 2016. Similarly, the number of companies operating Texas crowdfunding portals has fallen from nine in 2015 to only one in 2019.

As of April 30, 2019, the SEC hosts only 44 crowdfunding portals nationally. The number of portals on both the SEC and TSSB websites has declined due to the lack of profit, says McBride. “The portals make their money from people making transactions, so you have to have some volume there.”

A major reason for this cooling, according to McBride, has to do with the amount of work companies must put into creating an equity crowdfunding campaign and then maintaining their fiduciary responsibilities to their investors.

“I think a lot of people found the rules more cumbersome than what they thought they would be. The market just hasn’t liked it,” McBride says. “Most of the companies found out it wasn’t worth the work that has to go into it, so it comes down to [a need for] rule revision.”

Iles believes some Texas businesses will continue to use equity crowdfunding. TSSB’s program recently was tweaked to mirror the federal program, and Iles anticipates future changes will only improve it.

The value of equity crowdfunding, he says, is simply that it offers small businesses and entrepreneurs another tool to obtain capital.

“Equity crowdfunding goes along with the donor-based crowdfunding philosophy,” he says. “It’s helping the folks you know at the coffee shop and the hair salon, or the customers who like a business and are investing in it out of a sense of goodwill rather than pure investment motivation.” FN