Economic Growth and Endangered Species ManagementComptroller division protects environment and local economies

Lizards and mussels and butterflies … oh my! Texas has a variety of rare plant and animal species. Yet the federal government's primary tool for protecting such species, the Endangered Species Act (ESA), is often seen as an inflexible and costly law that can affect an area's agriculture, real estate development, construction and energy production.

Photo courtesy of Michael O'Brien.

In Texas, however, an effort is under way to assist landowners, communities and businesses in working effectively with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the federal agency that administers all ESA actions other than those concerning marine life. This science-based process, led by the Comptroller's office, includes state agencies, universities, community groups and private landowners, guided by a common dedication to the preservation of Texas' natural resources and the state's economic health.

A major focus of the work is adding to the pool of knowledge about species under consideration for ESA protection. Often, relatively little is known about the population, range, habitat and needs of such species, providing a poor basis for decisions that can have major economic consequences.

Since 2013, the Legislature has appropriated $10 million to the Comptroller's office for high-quality research on species under review for endangered species listing. At this writing, about $9 million has been expended to support research on these species (Exhibit 1). An additional $5 million has been approved for the 2018-19 biennium.

In addition to funding research, the Comptroller serves as presiding officer of the Interagency Task Force on Economic Growth and Endangered Species. Created by the Legislature in 2009, the task force is a group of state agencies that assists landowners, businesses and communities in working with endangered species issues and assessing their economic impact.

EXHIBIT 1: COMPTROLLER RESEARCH FUNDING FOR SPECIES UNDER ESA REVIEW

Source: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

New Comptroller division

Soon after taking office in January 2015, Comptroller Glenn Hegar centralized and focused the agency's ESA responsibilities by creating the Economic Growth and Endangered Species Management Division and recruiting Dr. Robert Gulley as its director.

In many ways, Gulley's work for the Comptroller's office marks the culmination of his professional experience. His résumé includes a doctorate in anatomy and neurobiology, with research at universities and the National Institutes of Health that resulted in 36 scientific publications. In addition, Gulley has more than a quarter-century of experience as an environmental attorney, including seven years with ESA cases as a senior trial attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice.

In particular, Gulley's success in helping to quell a 50-year-old fight concerning the Edwards Aquifer made him especially well-suited to head the new agency division.

As program manager for the Edwards Aquifer Recovery Implementation Program, and then as executive director of the Habitat Conservation Program at the Edwards Aquifer Authority, Gulley helped a diverse array of stakeholders reach a consensus in a decades-old battle between users of the aquifer's waters and conservationists. The agreement meets the water needs of a growing economy while protecting eight species listed under the ESA.

Dr. Robert Gulley,

Director, Economic Growth and Endangered Species Management

Gulley says Hegar was very specific in his direction to provide "good science" for Texas stakeholders, as well as transparent information for the public at large.

"We're committed to providing information and assistance to potentially affected stakeholders, and to supporting good science, so the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service can make an informed decision as to whether a species needs the protection of the Endangered Species Act," Gulley says.

Gulley's division comprises just six people including himself, but makes up for its small size with dedication and tenacity. In addition to Gulley, three staff members have scientific backgrounds. And the entire group is involved in the research supported by the Comptroller, taking courses in topics such as mussel identification, environmental modeling and riparian restoration. They also observe researchers' field activities to better understand their work.

The black rail loves to hide in coastal salt marshes. Scientists can mark and band captured black rails to evaluate their populations. Photo courtesy of Woody Woodrow, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Yet as Gulley explains, "It's important to remember that it's not our jobs to be scientists. We work with scientists. It's our job to understand the Endangered Species Act and the science that's required for it, and the species themselves, and to be able to communicate effectively with researchers so we can make sure their work is useful to FWS in its decisions with respect to species at risk."

Uncertainty

ESA requirements involve uncertainties that can be problematic for landowners and businesses.

"When a species is listed as endangered, or is a candidate for listing, the biggest consequence can be the lack of certainty for businesses and local governments that are trying to plan their activities," Gulley says. "You have private landowners and industries that want to use the land, and they'll do the work needed to take care of the species — they just want to know what the work is, so they can plan for it and keep their costs down.

"Again, our primary role is providing information," he says. "FWS may see a species that could be listed. Maybe we can come up with voluntary conservation measures that will allow us to do what we need to do to protect that species, and see that we keep the commitments we make to FWS."

"Game-changing" species

Soon after becoming division director, Gulley began identifying "game-changing" species that, if listed as endangered, could involve significant economic impacts within an area.

The monarch butterfly qualifies, as its annual migration pattern covers Texas, as does the Sprague's pipit, a tiny bird that winters in Texas. Both are affected by disappearing grassland habitat and food sources. Yet another is the spot-tailed earless lizard, whose territory lies in the middle of the energy-rich Eagle Ford shale.

But perhaps the biggest immediate project facing the Economic Growth and Endangered Species Management Division involves Texas' freshwater mussels. The Comptroller's office has allocated more than $3.6 million for research on 12 different Texas river mussel species under consideration for ESA listing. The money has been put to use in a variety of projects designed to understand potential threats to the mussels.

"Species in the Brazos, Colorado and Guadalupe rivers affect a big swath of the state's economy, and you can transfer that knowledge to East Texas mussels in the Sabine and Trinity rivers," Gulley says.

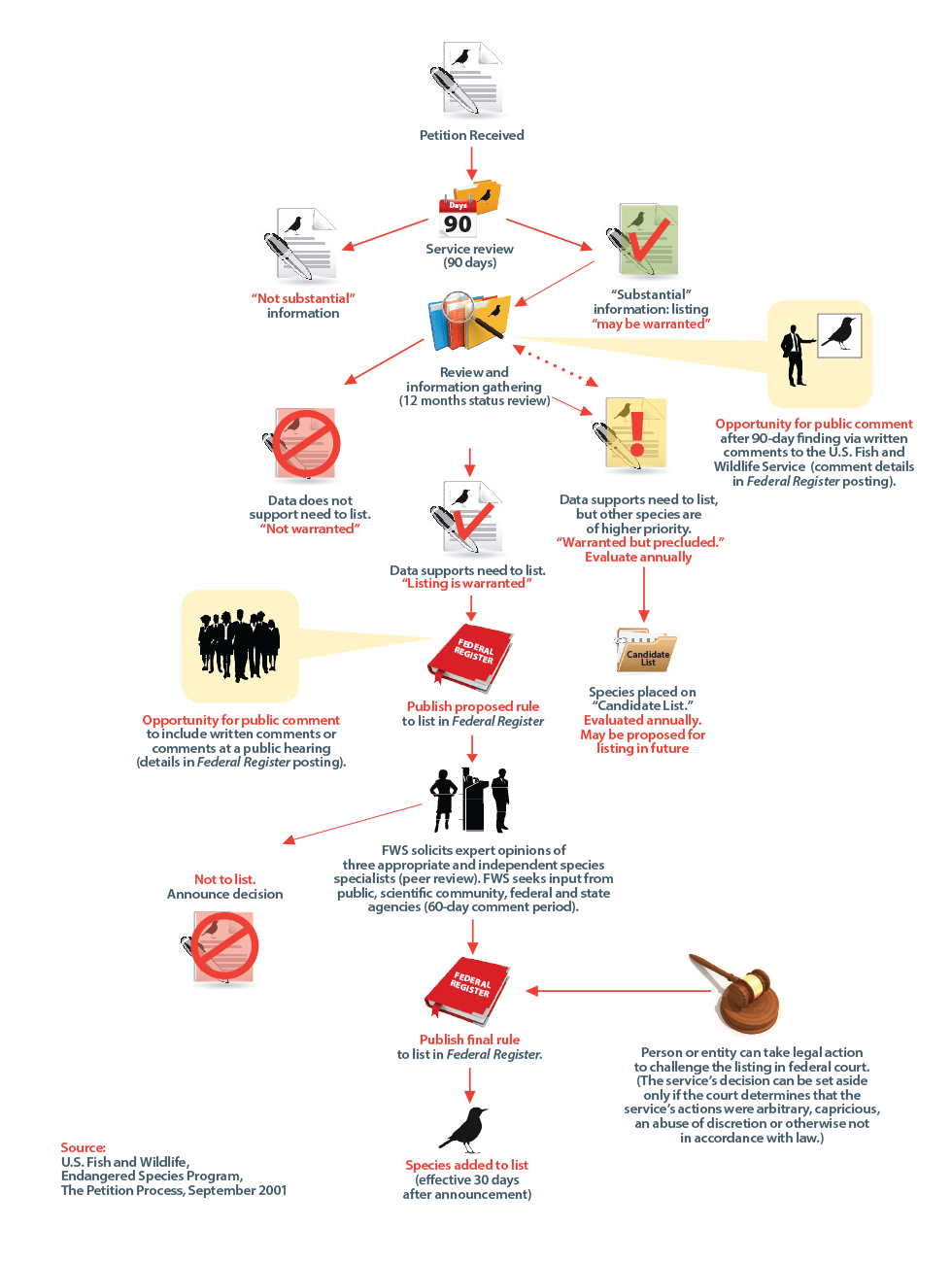

Exhibit 2: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Process for Listing Endangered Species

FWS follows a complex, multi-step process to determine whether a species deserves protection under the Endangered Species Act.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Process for Listing Endangered Species

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) follows a complex, multi-step process to determine whether a species deserves protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Once a petition for listing is received, it undergoes a “service review” for up to 90 days. If FWS decides a listing may be warranted, it moves to a 12-month status review period for information gathering and public comment.

At this point, FWS may decide that the data do not support a need to list the species; that the data do support the need to list the species, but other species are of a higher priority, in which case the species will be placed on a candidate list and reevaluated annually; or that listing is warranted.

If FWS concludes that listing is warranted, it will publish a proposed rule in the Federal Register. At this point, a period for public and written comment begins. This period may include public hearings. FWS will also seek the expert opinion of three appropriate and independent species experts, as well as input from the public, the scientific community and federal and state agencies.

If FWS decides to list the species, it will publish a final rule in the Federal Register. The species is added to the endangered species list 30 days after the announcement in the Federal Register.

Any person or entity can take legal action to challenge the listing in federal court. The service’s decision can be set aside only if the court determines that the service’s actions were arbitrary, capricious, and abuse of discretion or not otherwise in accordance with law.

Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered Species Program, “The Petition Process,” September 2001.

A team effort

Because the Comptroller's research funding is offered via contracts with hard deadlines rather than grants, the information produced can be shared with other universities, FWS, state agencies such as Texas Parks and Wildlife and concerned communities and landowners much more quickly. Information and reports are shared through meetings open to the public.

An interagency work group from the Comptroller's office, FWS, Texas Parks and Wildlife, Texas State University and others participate in a field exercise.

Photo courtesy of Woody Woodrow, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

"This has never happened before," says fisheries expert Dr. Timothy H. Bonner with Texas State University. "We've never had this amount of discussion and people talking with one another and sharing data. The comptroller has done a good job of keeping everyone informed."

Dr. Kenneth G. Ostrand, director of FWS' San Marcos Aquatic Resources Center, says his agency appreciates the information provided by the Comptroller's office.

"We're getting in early with these species, and typically our job is to catch up," Ostrand says. "With these animals, we're at the beginning of the listing process, and actually have the luxury, for once, to approach this in a calm and logical way. Hopefully, it will result in a much greater success in the end, and eliminate the need for [endangered species] listing. It sounds strange, but we're trying to put ourselves out of business."

Ostrand says he finds the inclusion of the public as well as the research community in the process refreshing. Public meetings allow stakeholders who might be affected by an endangered species listing to ask questions and voice concerns. And informal working groups meet throughout the year to gather information from experts and input from stakeholders. All meetings are open to the public and announced on the Comptroller's website as soon as they're scheduled.

Comptroller analyst Kimberly Horndeski consults with Dr. Kenneth Ostrand, director of the FWS San Marcos Aquatic Resources Center, on the progress of the center's mussel propagation study.

"The Comptroller's office has a plan and a vision for the future of Texas, particularly from an economic perspective," Ostrand says. "They understand the link between the species, the environment and economic success."

Josh Able of the San Marcos Aquatic Resources Center demonstrates a feeding system designed to support freshwater mussels as part of a study commissioned by the Comptroller's office.

Dr. Kenneth G. Ostrand,

Director,

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, San Marcos Aquatic Resources Center

Good science, good decisions

Gulley understands his position within the Comptroller's office is unusual.

"There's hardly a time I speak at a conference that I'm not asked, ‘Why is the Comptroller's office involved with endangered species?'" says Gulley. "And the answer is we're trying to assist state and local agencies, industry and the citizens of Texas.

"If you look at the Endangered Species Act, there are very few places that allow for economic considerations," Gulley explains. "But the comptroller believes the best way to ensure economically sound decisions are made is to ensure the science is good and current. And if we do that, the Fish and Wildlife Service will make better decisions and have less impact on the state economy." FN

Learn more about the work of the Economic Growth and Endangered Species Management Division.