Certificates of ObligationA Flexible Funding Tool for Local Projects

Texas state law generally requires our local governments to seek voters’ approval before issuing debt that will be repaid from tax revenues. And every year, in May and November, voters across the state are asked to approve new bond debt for the construction of city and county buildings, hospitals, schools, water infrastructure and much more.

One common form of borrowing, however, represents an exception to this rule: certificates of obligation (COs), which some local governments can use to fund public works without voter approval.

COs provide local governments with important flexibility when they need to finance projects quickly, as with reconstruction after a disaster or as a response to a court decision requiring capital spending. But the way COs circumvent voter approval has made them controversial in the past, leading to 2015 legislation restricting their use.

Certificate of Obligation Basics

COs initially were authorized by Texas’ Certificate of Obligation Act of 1971. Cities, counties and health or hospital districts can use them to fund the construction, demolition or restoration of structures; purchase materials, supplies, equipment, machinery, buildings, land and rights of way; and pay for related professional services. COs are issued for terms of up to 40 years and usually are supported by property taxes or other local revenues.

COs often are associated with emergency spending, but their use isn’t restricted to such purposes. They can be used to fund public works as part of standard local government operations.

Commissioners courts, city councils and health or hospital district boards opting to issue COs must post a description of the projects to be financed in local newspapers at least twice, first more than 30 days before the governing body’s vote on the CO issuance and again a week after the initial posting. These postings must describe the general purpose and amount of the debt to be issued, name the method of repayment and list the time and place of the governing body’s vote.

And, again, COs do not require voter approval unless 5 percent of qualified voters within the jurisdiction petition for an election on the spending in question.

Local governments pay for public infrastructure projects by issuing long-term debt, either through COs or the more common general obligation (GO) bonds, which require voter approval; or through revenue bonds that must be backed by a specific revenue stream, sometimes generated by the project itself. Given their streamlined adoption process, COs can be particularly attractive when a local government wishes to, for example, take quick advantage of lower interest rates, purchase a newly available property or come into compliance with a federal or state regulation.

According to the Texas Bond Review Board (BRB), CO debt held by cities, counties and hospital/health districts made up 16 percent of their total debt obligations in 2015, but just 6 percent of all local government debt. (By contrast, school districts carry 34 percent of Texas local government debt.) By the end of fiscal 2015, cities held more than three-quarters of outstanding CO debt (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Total Certificate of Obligation Debt Held by Texas Local Governments, 2015 (In Millions)

| Jurisdiction | Total CO Debt | Percent Share |

|---|---|---|

| Cities | $10,327.4 | 75.6% |

| Counties | $2,473.6 | 18.1% |

| Hospitals and Health Districts | $864.8 | 6.3% |

| Total | $13,655.8 | 100.0% |

Source: Texas Bond Review Board

CO debt rising fast

According to the BRB, between fiscal 2006 and fiscal 2015 outstanding CO debt issued by cities, counties and hospital/health districts rose by nearly 85 percent, substantially faster than the 50 percent growth rate for total debt held by these entities. The growth in CO debt outstanding also outstripped total debt growth in each type of jurisdiction allowed to issue them (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Growth in Outstanding Certificate of Obligation Debt vs. Total Debt, 2006-2015 (In Millions)

- CO DEBT

- TOTAL DEBT

| Jurisdiction | CO Debt Outstanding 2006 | CO Debt Outstanding 2015 | Percent Increase in CO Debt | Percent Increase in Total Debt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities | $5,887.8 | $10,327.4 | 75% | 45% |

| Counties | $1,341.0 | $2,473.6 | 84% | 57% |

| Hospitals and Health Districts | $150.3 | $864.8* | 475% | 168% |

* The bulk of this debt represents $696 million in CO debt approved by the Bexar County Hospital District in 2009 to finance its Master Facility Plan.

Source: Texas Bond Review Board

CO issuance rose by an annual average rate of 36 percent between fiscal 2006 and 2015. Annual economic growth during this period averaged 8 percent for cities, 62 percent for counties and 35 percent for health and hospital districts.

In addition to examining the overall growth in the use of COs, it’s useful to consider how voters in specific geographic regions are affected by CO debt. In some areas, political subdivisions issuing CO debt overlap with one another, creating concentrations of outstanding CO debt. This is particularly evident in major metropolitan counties.

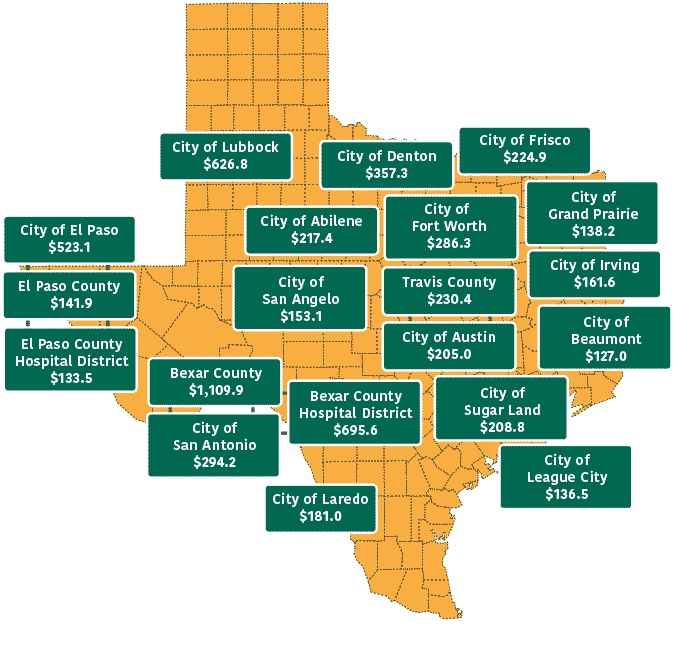

In Bexar County, for instance, the county, its hospital district and the city of San Antonio all are among the top 20 Texas jurisdictions in terms of outstanding CO debt (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Twenty Texas Jurisdictions with the Largest Outstanding CO Debt, 2015 (In Millions)

| Jurisdiction | CO Debt Outstanding 2015 (millions) |

|---|---|

| Bexar County | $1,109.90 |

| Bexar County Hospital District | $695.6 |

| City of Lubbock | $626.8 |

| City of El Paso | $523.1 |

| City of Denton | $357.3 |

| City of San Antonio | $294.2 |

| City of Fort Worth | $286.3 |

| Travis County | $230.4 |

| City of Frisco | $224.9 |

| City of Abilene | $217.4 |

| City of Sugar Land | $208.8 |

| City of Austin | $205 |

| City of Laredo | $181 |

| City of Irving | $161.6 |

| City of San Angelo | $153.1 |

| El Paso County | $141.9 |

| City of Grand Prairie | $138.2 |

| City of League City | $136.5 |

| El Paso County Hospital District | $133.5 |

| City of Beaumont | $127 |

Source: Texas Bond Review Board

Examples of 2015 CO issuances include $67 million issued by the city of Abilene for extensions and improvements to its water supply, and $60 million issued by Williamson County to fund construction of new buildings and renovations to existing structures for the Sheriff’s Office and the county’s emergency medical services. Health and hospital districts, by contrast, issued no certificates of obligation in 2015.

Pros and Cons

Many Texans, including legislators, are concerned about rising levels of local debt. According to BRB, Texas ranks second-highest among the 10 most populous states for per-capita local debt. Certificates of obligation, unsurprisingly, have come under considerable scrutiny in recent years.

As noted previously, proponents tout the flexibility CO bonds afford local officials in responding to critical and emerging public needs, allowing them to act without having to wait for — or pay for — an election. And unlike general obligation bonds, a single CO can be issued to support more than one purpose or project, reducing the cost of issuance.

Local governments often use COs to refinance or reduce interest rates on existing debt, enjoying substantial savings. At times, they can help reduce costs in other ways.

The city of Denton, for instance, began issuing COs to fund utility system projects in 2010, in response to the collapse of the municipal bond insurance industry following the 2008 financial crisis. Denton had previously employed revenue bonds for utility projects, repaying the bonds with revenue from utility payments. Without bond insurance, however, Denton would have had to pay a far higher interest rate on the revenue bonds. Bryan Langley, Denton’s assistant city manager, says the city’s use of COs rather than revenue bonds between fiscal 2010 and 2016 saved it more than $2.3 million in interest costs, an amount it subsequently dedicated to street improvements.

Opponents, on the other hand, say COs allow local officials to burden taxpayers with long-term, tax-funded debt without adequate citizen input or approval, and that the ability to fund multiple projects with a single CO issuance is confusing and disguises public indebtedness.

They also point out that the provision requiring at least 5 percent of voters to petition for an election on CO debt is a significant hurdle in metropolitan areas.

New Limitation on CO Powers

Opposition to COs came to a head a few years ago in Montgomery County, north of Houston. In 2012, the Montgomery County Commissioner’s Court issued $30 million in COs for a road project in Conroe, less than a year after voters rejected a $200 million bond proposal including the same project.

As a result, area citizens pressed for legislation to curtail their use, culminating in 2015’s H.B. 1378, which prohibits the issuance of COs for any project voters rejected in the preceding three years. Exceptions include a “public calamity” that threatens property or public health, or the immediate need to comply with a state or federal regulation, rule or law.

It’s probably too soon to weigh the impact of H.B. 1378, which took effect in January 2016. But regulators have reported that local officials seem to be using more specific language in general obligation bond proposals, to preserve their ability to issue CO bonds for related projects in the future. For example, instead of a GO bond proposal for “city center street improvements,” the proposal might specify the streets to be improved, so that if voters reject the GO bonds, COs still can be issued for other street projects in the city center.

According to the BRB, CO issuance has risen by 19 percent since January 2016. CO issuance varies widely from year to year, however, and it’s unclear whether the new law has had any effect on the frequency of CO issuance.

Other states have considered similar action to regulate debt issuance without voter approval. North Carolina’s Senate Bill 129, passed in 2013, caps statewide non-voter-approved debt at 25 percent of the state’s total bonded indebtedness. In New York state, which carries the nation’s largest state and local per-capita debt burden, lawmakers proposed a bill that, if approved, would have required voter approval for all new state debt, with only limited exceptions.

In addition to H.B. 1378, Texas lawmakers have proposed a variety of other changes to CO law, including restrictions on the kinds of services that can be purchased with COs and changes to the requirements for notice of intent to issue COs. Similar bills may reemerge in the upcoming legislative session, as the movement toward greater financial transparency grows. FN