Capital Appreciation Bonds Another Finance Option for Schools

Forney, just east of Dallas in Kaufman County, is one of Texas’ 10 fastest-growing cities. Once a small town known primarily for its antique shops, Forney’s population has more than tripled in the past 15 years.

This growth has brought new opportunities for Forney’s citizens. It also brings challenges, however, as the city struggles to keep up with the rapidly growing demand for infrastructure, facilities and services.

Consider, for example, the Forney Independent School District, which has seen its enrollment rise by 330 percent in the past 15 years. In 1999, with an enrollment just above 2,000, Forney ISD comprised four campuses. By 2014, the district had grown to include 14 campuses and more than 8,600 students.

For Forney ISD — and many other Texas school districts experiencing similarly rapid enrollment growth — coping with the influx of new students is difficult at best.

Traditionally, school districts have raised money for campus construction projects by issuing municipal bonds, repaying investors’ principal and interest with property tax revenues. But in Texas, school districts face a limit on the amount of debt they can incur. Since 1991, a state law commonly called “the 50-cent test” has required districts to show they can repay their bonds with a tax rate of no more than 50 cents per $100 of assessed property value at the time of issuance.

Districts already at or near the 50-cent limit, such as Forney ISD, have sought other financing options. To build and renovate the facilities they need to meet the demands of burgeoning enrollment, some districts have turned to an alternative form of debt called a capital appreciation bond (CAB).

How CABs Work

A CAB is a debt instrument governments can use to fund buildings, parks, roads and other capital projects. For conventional bonds, principal and interest payments are made in installments, generally once a year for principal and twice a year for interest. CABs, by contrast, require no payments of any kind until maturity — the date on which the debt becomes due. At that time, the full amount of the principal and all interest accrued must be repaid to the investor as a single lump sum.

Thus interest on CAB debt compounds throughout the bond period, which may be years or even decades.

A school district issuing CABs, then, does not have to increase its tax rates to cover interest and principal payments until the bond matures. This feature is why many Texas school districts have turned to CABs — it helps them borrow money for decades without exceeding the 50-cent cap.

The assumption is that, by the time the bond matures, the district’s tax base will have expanded enough to allow it to pay the lump sum of principal and interest.

Pros and Cons

Proponents of CABs say they help fast-growing districts cope with increasing enrollment when their tax bases have not yet caught up to their growth. In Texas, CABs present an increasingly popular financing option for districts, typically smaller and/or faster-growing than average, which are at or close to the state’s 50-cent limit on bond debt (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Fast-Growth* Texas School Districts with Debt Service Tax Rates Close to or at the 50-Cent Cap

| District | County | Enrollment, 2015 | Enrollment Growth Rate, 2010 to 2015 |

Debt Service Tax Rate, 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosper ISD | Collin | 7,060 | 95% | $0.50 |

| Lubbock-Cooper ISD | Lubbock | 5,307 | 43% | $0.50 |

| New Caney ISD | Montgomery | 12,937 | 35% | $0.50 |

| Anna ISD | Collin | 2,858 | 28% | $0.50 |

| Manor ISD | Travis | 8,819 | 28% | $0.48 |

| Princeton ISD | Collin | 3,787 | 27% | $0.45 |

| Dripping Springs ISD | Hays | 5,410 | 25% | $0.48 |

| Liberty Hill ISD | Williamson | 3,210 | 25% | $0.50 |

| Schertz-Cibolo-Universal City ISD | Guadalupe | 14,586 | 25% | $0.45 |

| Hays ISD | Hays | 17,904 | 23% | $0.50 |

| Hutto ISD | Williamson | 6,177 | 21% | $0.50 |

| Frenship ISD | Lubbock | 8,811 | 21% | $0.48 |

| Leander ISD | Williamson | 36,105 | 19% | $0.47 |

| Crandall ISD | Kaufman | 3,291 | 19% | $0.48 |

| Denton ISD | Denton | 26,746 | 19% | $0.50 |

| Lovejoy ISD | Collin | 3,810 | 19% | $0.50 |

| Dickinson ISD | Galveston | 10,391 | 18% | $0.50 |

| Wylie ISD | Collin | 13,978 | 16% | $0.47 |

| Forney ISD | Kaufman | 8,982 | 15% | $0.50 |

| Royse City ISD | Rockwall | 5,061 | 15% | $0.50 |

| Little Elm ISD | Denton | 6,921 | 14% | $0.50 |

| Allen ISD | Collin | 20,554 | 14% | $0.48 |

| White Settlement ISD | Tarrant | 6,646 | 13% | $0.50 |

| Needville ISD | Fort Bend | 2,911 | 12% | $0.56** |

| Burleson ISD | Johnson | 10,957 | 11% | $0.50 |

Note: Not all of these districts have used CABs.

*The Fast Growth School Coalition identifies a “fast-growth” school district using the following criteria: (1) enrollment of at least 2,500 students during the previous school year and either (2) enrollment growth over the last five years of at least 10 percent or (3) 3,500 or more students.

** Needville ISD was already above 50 cents when the cap became law.

Sources: Texas Education Agency and Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

CABs generally offer longer terms than conventional bonds, allowing investors to reap a greater amount of compounded interest over time — and allowing borrowers to defer debt service payments for decades. CABs allow school districts to "build now, pay later" — "later" being many years down the road, when the tax base may have grown enough to make repayment less of a burden. Some districts may set aside money along the way to ease the burden when their CABs reach maturity.

Overreliance on CABs, however, can be costly for school districts when the eventual lump-sum payments become due. According to Texas Bond Review Board (BRB) data, as of the end of fiscal 2014 Forney ISD had issued four of the 20 most expensive CABs outstanding for Texas school districts. For just under $30 million in immediate funding, the district will have to repay more than $208 million when the bonds reach maturity in 30 to 40 years.

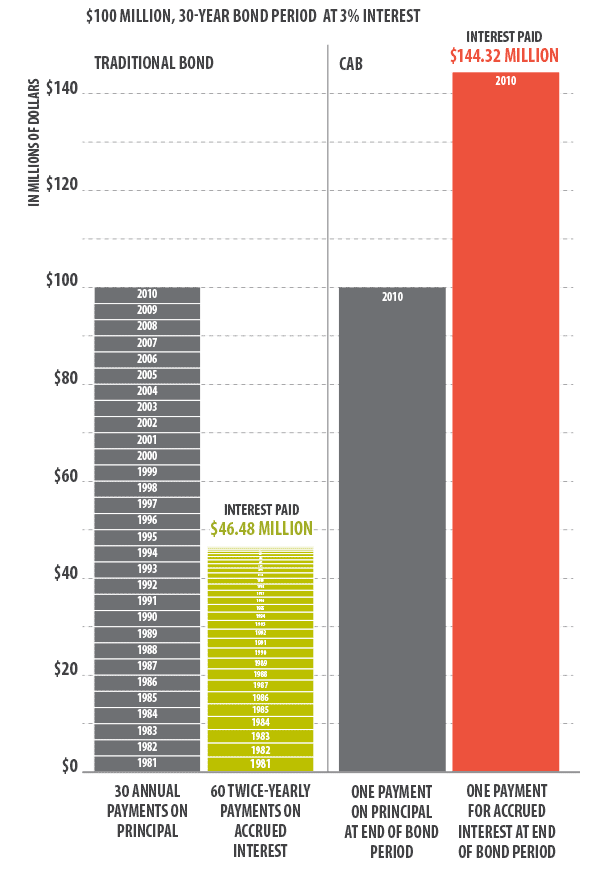

Due to compounded interest, CABs can be much more expensive for borrowers than traditional municipal bonds (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Traqditional Bonds vs. Capital Appreciation Bonds

To understand the difference between traditional bonds and CABs, consider a district seeking $100 million with a 30-year maturity and a 3 percent interest rate. With a traditional bond issue, principal and interest are repaid over the entire 30-year term. CABs allow the district to avoid any payments until maturity — but interest payments will be more than three times higher.

Source: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

CABs in Texas

Texas school districts have used CABs for decades, sometimes for construction projects and sometimes to refinance existing debt, and thus avoid spikes in tax rates. According to data submitted to the BRB, school districts accounted for 99 percent of all CABs issued in Texas in fiscal 2014. In that year, CAB debt represented 5.1 percent of all school bond debt.

While the BRB staff acknowledges that CABs can be an effective financing tool — if used moderately and with reasonable terms — an analysis prepared by them in 2014 noted that heavy CAB use can result in a downgrade of a district’s bond rating.

Some Texas lawmakers have expressed concern that several fast-growing school districts are using the bonds to sidestep the 50-cent debt limit, gambling on growth in the tax base while sharply increasing the overall debt to be thrust on future generations.

Texas’ Fast Growth School Coalition, a network of school leaders facing the challenges of rapidly increasing enrollment, maintains that CABs are necessary because of the state’s limit on bond debt, which prevents many districts from incurring additional debt even when voters approve it.

Limits on CABs

CABs are controversial due largely to the way the associated debt can balloon over time. California and — recently — Texas have enacted limits on the use of CABs; Michigan has banned them altogether.

In 2013, California enacted a law limiting total debt service on CABs to four times the principal plus a maximum of 25 years’ worth of interest. The law also requires CAB transactions to allow for early repayment of the debt when terms are longer than 10 years. The law originated, in part, due to media reports that $105 million in CABs issued by San Diego-area Poway Unified School District would ultimately cost the district nearly $1 billion.

The 2015 Texas Legislature considered several bills pertaining to CABs, but only one, House Bill 114 by Representative Dan Flynn of Northeast Texas, became law.

H.B. 114, which went into effect Sept. 1, 2015, prohibits Texas local governments from issuing CABs secured by property taxes with terms of more than 20 years, and (with some exceptions) from refunding CABs to extend their maturity dates. It also limits each government’s CAB debt to no more than 25 percent of its total outstanding bond debt. CAB issuers, moreover, must provide certain information to the public, including the total amount sought through the CAB issue, its length of maturity and purpose, as well as the issuer’s total outstanding bond debt and the amount of principal and interest to be paid at maturity.

Using CABs

When properly used, CABs can provide funding for local governments that are growing rapidly — those that know their tax bases will increase, thus allowing them to handle greater future costs. CABs can be a very expensive form of borrowing, however, leaving large debts to accrue in the decades to come. Both the risks and advantages of CABs should be considered when determining the best option for funding. They may be an option in some cases, but should be approached with caution.

As for Forney ISD, the district issued a press release in April 2015 announcing it will issue no new debt through 2027. While the district is working on other solutions to address anticipated growth, its decision to halt borrowing will help to ensure fiscal responsibility and, as the press release concluded, “to develop into a strong and efficient District.” FN

For more information on Texas local government debt, visit the Comptroller’s Debt at a Glance tool and the Texas Bond Review Board.