Keeping Up with the Jones Act Has a Protectionist Law Outlived its Usefulness?

Texas energy producers know there’s more to navigate than water when transporting oil and other petroleum products from Texas seaports to refineries along the East Coast.

The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, better known as the Jones Act for its original sponsor, Washington Sen. Wesley Jones, is a federal law regulating cabotage, or naval transport in U.S. coastal waters and between domestic ports, as well as other aspects of the maritime industry.

Under the Jones Act, foreign carriers and crews are banned from domestic water routes. Cabotage from one U.S. port to another is restricted to U.S.-built, -crewed and -flagged vessels. The requirement was a protectionist economic strategy designed to assist America’s shipyards and maritime fleet.

Expensive Shipping

Today, however, this Jones Act requirement entails a burden for shippers, due to higher costs involved in using U.S. vessels. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration (MARAD), the total average cost of operating a U.S.-flagged vessel is 2.7 times higher than that incurred by foreign-flagged counterparts.

MARAD reports that, on average, crews on U.S.-flagged vessels are paid 5.3 times more than those on foreign-flagged ships. Adding to the disparity is the fact that foreign-flagged ships pay few or no U.S. taxes, while U.S. shipping companies pay combined tax rates as high as 38 percent.

Another factor driving the high cost of cabotage under the Jones Act is the cost of U.S.-built tankers, which far exceeds that of foreign-built vessels. Texas oil headed by water for northeastern refineries often travels on coastal tankers, also called “handysize” or “medium-range” tankers, capable of carrying 300,000 to 650,000 barrels of crude. American-made ships of this type can cost between $100 million and $135 million, at least three times what they cost on world markets.

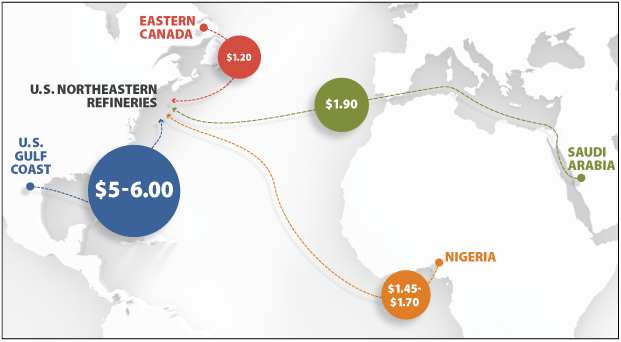

And with a limited number of U.S.-built tankers available to transport goods from one U.S. port to another, moving oil can be an expensive logistical nightmare for Texas producers. At present, it’s several times cheaper to ship oil to northeastern ports from Nigeria and Saudi Arabia than from the Gulf Coast (Exhibit 1).

Many Texas companies believe the Jones Act has outlived its usefulness.

Exhibit 1: Ocean Shipping Rates to U.S. Northeastern Refineries (In dollars per barrel)

Source: Congressional Research Service, “Shipping U.S. Crude Oil by Water: Vessel Flag Requirements and Safety Issues,” July 21, 2014

Economics vs. Security

“I don’t like the Jones Act because it makes no economic sense,” says Dr. Bernard L. Weinstein, an economist and associate director of Southern Methodist University’s Maguire Energy Institute. “It’s simply a form of protectionism to a very small industry. I think you have to weigh that against the benefit to consumers and more energy security from more domestic refining and less imported crude.”

But Dr. Joan Mileski, head of the Maritime Administration Department at Texas A&M University at Galveston, says the Jones Act encompasses more than just economic protectionism - it also contributes to national security.

“The Merchant Marine supports the navy,” explains Mileski. “The people we train on our campus become officers for the Merchant Marine, and although most of the time they work for commercial companies, in case of war, U.S.-flagged ships could be commandeered to help. That’s part of why the Jones Act exists.”

Mileski admits that from a market perspective, the Jones Act is a barrier to trade. “But the question involves safety and security. I'm all for free markets, but I'm also a maritime security person,” she says. “If we totally lifted the Jones Act, any foreign-flagged ship could go anywhere on our waterways, including up the Mississippi River.”

Texas Considerations

Texas’ energy industry certainly feels the effects of the Jones Act. The state’s own petrochemical refineries are primarily set up for heavy Middle Eastern oil. Most U.S. refineries capable of refining Texas’ light, sweet crude are located along the East Coast, making cabotage essential.

“We have a surplus of light crude coming out of the Eagle Ford, and most refineries along the Gulf Coast are geared toward the heavier crude, so we're exporting from Corpus Christi and Houston to the Northeast,” explains Weinstein.

“I suspect if the Jones Act were lifted, we would see a tremendous increase in the volumes of oil going from Texas to the Northeast,” he says. “This would be a good way to not only supply our oil to our refineries, but also reduce the dependence of northeastern U.S. refineries on imported crude.”

Anti-Jones Act…

Weinstein points to the influence powerful special-interest groups and union lobbyists have with Congress as the reason for the Jones Act’s continued existence. Efforts to repeal all or part of the act have been debated in Congress for years, with no effect.

The most recent attempt to modify the act was made by Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who proposed an amendment to the Keystone Pipeline bill in January 2015 that would repeal the cabotage provision; it failed to pick up the support needed to bring it to a vote.

Calling the Jones Act antiquated, McCain cited findings from the Congressional Research Service, which put the cost of moving crude oil from the Gulf Coast to the northeast U.S. at up to $6 per barrel on a Jones Act tanker, versus $2 per barrel on a foreign-flagged tanker transporting the same crude from the Gulf Coast further north to a Canadian refinery.

“Foreign-flagged vessels carry crude oil all around the world, and have been doing so for the last 60 years,” says Weinstein. “If you look at the volumes transported, an oil tanker is a lot safer than rail tanker cars if you're looking at spillage rates.

“And yes, there have been a couple of accidents, but relative to the amounts of crude transported, the accidents have been fairly minor,” he says. “A foreign-flagged vessel entering or leaving a U.S. port must meet all the safety standards of the U.S. Maritime Administration.”

…and Pro

There’s no doubt that the Jones Act cabotage provisions have a significant impact on the U.S. economy. The Congressional Research Service reports that the U.S. has 128 Jones Act-eligible vessels capable of delivering oil between American ports, as well as several thousand eligible river barges (Exhibit 2). According to MARAD, these vessels support nearly 500,000 American jobs and create an economic impact of almost $100 billion.

Exhibit 2: Jones Act-Eligible U.S. Crude Oil Carriers

| Vessel | Capacity (in Thousands of Barrels) | Crew Size | Inventory* | Operating Geography |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| River Barge | 20-90 | 4 to 10 | 3,500-4,000* | Inland Rivers, Intracoastal Waterway |

| Seagoing Barge | 50-300 | 6 to 12 | 86* | Coastal U.S. |

| Handysize Product Tanker | 300 | 21 to 28 | 31* | Coastal U.S. |

| Aframax or Suezmax Crude Oil Tanker | 800-1,300 | 21 to 28 | 11* | Alaska to Puget Sound and California |

* For domestic service, vessels must be U.S. built and U.S. flagged.

Source: Congressional Research Service

MARAD also reports that in 2013, U.S. shipyards entered into contracts to produce hundreds of new vessels for cabotage, including oil tankers and container ships powered by liquid natural gas.

Jones Act supporters claim the higher costs of U.S. shipyards are justified when the results produce safe and reliable vessels with the latest technologies. The Jones Act has been cited as integral to the establishment of safety standards for vessels traveling in U.S. coastal waters.

Mileski says the extra cost is well worth it.

“From a safety standpoint, there’s no way to vet foreign-flagged ships,” she says. “You don’t know how they were made or what they have on them. Without the Jones Act, any tanker could pick up crude at one U.S. port, and then it’s going to sail all along the U.S. coastline, within 200 miles, all the way to Pennsylvania? We have to make sure that safety standards are at a level the U.S. can feel comfortable with.”

But more importantly, Mileski says, there’s the issue of national security. Without this maritime law, she says, foreign-flagged vessels controlled by foreign crews would have access to tens of thousands of miles of America’s inland waterways. U.S. commerce could find itself dependent on foreign vessels for global imports and exports.

All Jones Act ships must by crewed by U.S. citizens who possess U.S. federal transportation worker identification credentials (TWICs) as well as U.S. Merchant Marine credentials, she says. And Jones Act ships must provide documentation of what is being transported 96 hours prior to arrival in a U.S. port.

“Right now, the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Navy patrol the shoreline — they're our cops,” Mileski says. “U.S. ships are vetted, we know what’s on them and who’s on them. Without the Jones Act, we wouldn’t know that. A U.S. flagged ship must be crewed by U.S. citizens — everyone has a license and an identity. Without the Jones Act in place, we wouldn’t know who was on those ships.”

Oil Ban Impact?

Weinstein points out that the proposed elimination of the national ban on crude oil exports, recently approved by the U.S. House of Representatives, would have significant effects on the debate concerning cabotage.

“There’s a lot of talk now about removing the ban on oil exports, and I think that will happen in the next year or two,” he says. “That’s very important to sustain the industry. That’s another argument for repealing the Jones Act. It would encourage more domestic production, which right now is under a lot of pressure, with prices that are half what they were 18 months ago.

“Let the market determine how product goes from the wellhead to the refinery, whether it’s rail or pipeline or ship,” Weinstein says. “In the case of the Jones Act, we have an artificial barrier to competition, and I'm not just talking about competition between domestic and foreign flag carriers. I'm talking about competition between different modes of transport: rail, truck, tanker and pipeline.

“In the broad sense, we need to recognize the United States is the number-one energy producer in the world, and we need to engage more fully in the global market,” he says. “That means doing away with all artificial barriers to production and competition.” FN

Related:

- Texas Manufacturing (March 2018)

- Will an Expanded Panama Canal Increase Texas Trade? (April 2017)

- Texas Ports: Gateways to World Commerce (February 2017)